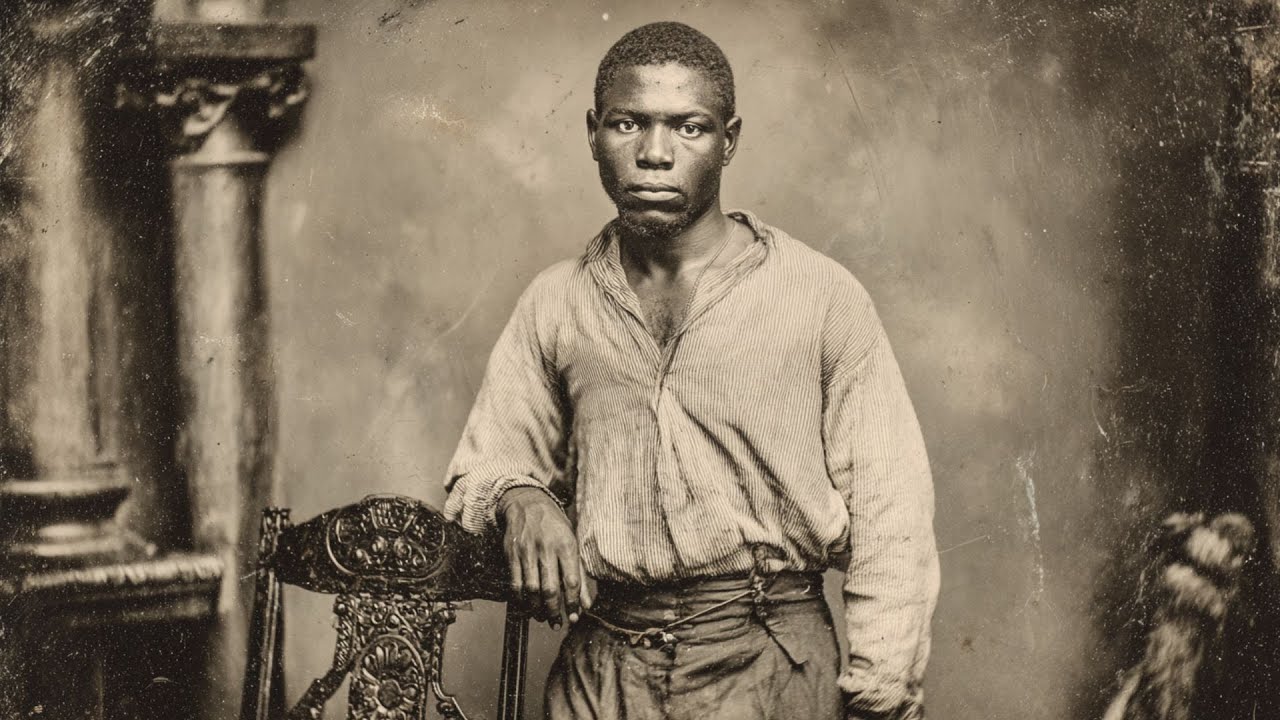

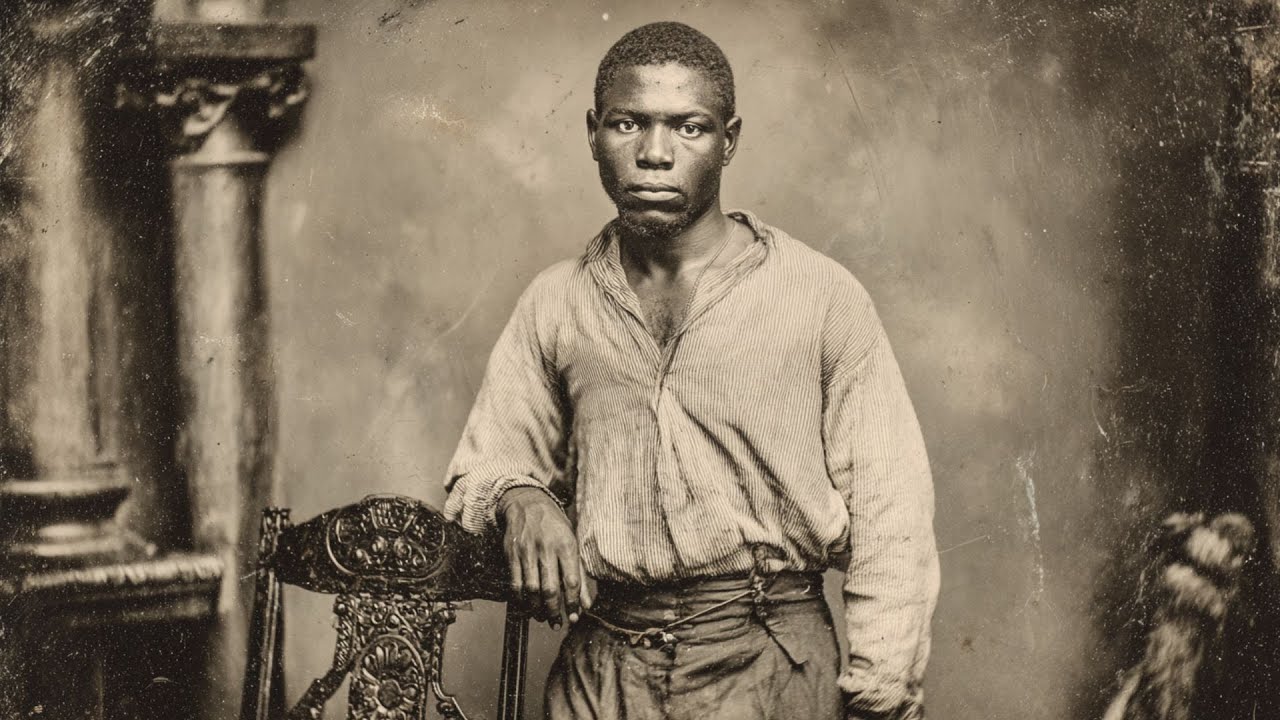

The photograph lived in a box for a century, sleeping under dust and polite forgetfulness. At first glance, it was the sort of image the era loved—a white house with columns, the light falling just right, dresses held stiff by whalebone and expectation. Men stood as if their posture could hold back a war. A household arranged like a still life around a prosperity no one intended to explain. Only in the corner, where the frame grew stingy and the emulsion softened, a man named Isaac stood with his hands brought forward in a fixed, formal way. For decades, people looked past him.

When archivist Margaret Hamilton examined the glass plate in 1963, she asked the photograph to tell the whole truth. She took a magnifier and followed the black lines and soft pale grays, and when she reached Isaac’s hands, she stopped. Inside the small glass he was holding—something you could mistake for a jar of polish in a house that always had a shine—a trio of pale, suspended shapes floated like a secret that needed a witness. Fingers. The kind of detail you don’t imagine because you’d rather not. It was a portrait which, once seen clearly, could not be returned to courtesy.

That image—taken in April 1861 on the Wilson plantation outside Montgomery—was meant to celebrate an engagement and a household order that felt to its keepers like faith. The photographer, a useful man named Frederick Sullivan, had lined everyone up the way one arranges heirloom pewter. Thomas Wilson, new to Alabama but not to the idea of dominion, stood in profile like a principle. His daughter—Elleanora to the pastor, “Nell” in letters she never expected curious eyes to read—held her fiancé’s arm and looked toward the future as if it would keep a promise. The enslaved appeared in the margins, named in inventories and allowances, not in the gentle ink of family Bibles. And in the corner, Isaac held the jar because he had been told to, because he had learned the consequences of not complying with the theater of someone else’s righteousness.

They said Wilson was different from neighboring planters. He was praised for being humane, a word that can be bent into any shape that suits the speaker. Church men nodded when he gave. Neighbors said his were better fed. Few ran. He quoted Scripture when he spoke about order. He had studied medicine for a season in Virginia before deciding bodies were better understood as labor. He kept diagrams and instruments in a back room he called the office, as if changing the name of a thing could change its soul.

Later, when the photograph was finally examined like evidence instead of decor, a pattern emerged from letters and ledgers that had outlived the men who wrote them. Wilson believed pain could be refined. That you could spare the skin and still break the will. He considered whips vulgar—more a sign of a master’s impatience than his skill. He preferred demonstrations, the sort of correction a man of science might discuss over coffee without staining the saucer. In his office were glass jars. He kept them on a shelf above his desk where the light caught them in the afternoon, a quiet constellation of suspended reminders.

There is a line in Elleanora’s journal from January 1861 that reads like the hinge in a door: Father showed Mr. Caldwell his method today and insisted it was superior to brutality. I excused myself when he brought out the jar. She did not explain what, precisely, her father had removed from sight and sense, but the entries around that one acquire a cold clarity once you know to look for it. She mentions a man named Isaac being present. She mentions a brother named Jacob who, months earlier, had vanished into the woods and returned with men on horses behind him, a wound that never healed because its purpose wasn’t to mend.

According to dusty records and fresher memories recorded a century later, Jacob did not survive his return. Wilson, committed to proof, kept what he considered useful of him. Not from curiosity, not from medicine, not in any way an anatomy class could condone. He preserved the fingers and made Isaac carry them. You don’t call it punishment when you want to keep your conscience clean; you call it instruction. You say the mind is more easily subdued than the body and pretend you’ve discovered a moral. Wilson taught with the sort of logic that sounds kinder until you follow it to its end.

The mind doesn’t bruise where neighbors can see. A man forced to hold his brother in a jar cannot lay him down; he cannot grieve properly; he becomes a warning that breathes. It is a cruelty that doesn’t raise its voice. It speaks in a tone you might recognize from schoolrooms and parlors: This is for your good. This is how order stands. This is how we love you, by breaking you clean.

In the years after emancipation, a few surviving accounts from neighboring fields spoke of the Wilson place like a story you tell to make sense of a feeling. They called that back room the office, and when someone came out of it, people noticed what was missing. They noticed the way Isaac stooped, not from age, but from the weight of something he was never allowed to set down. We are told he stopped speaking above a whisper. We are told he hid his hands when strangers looked at him. We are told he did not run because he did not believe his brother could. The jar burned within reach, always.

When the war took the fathers and the sons to other fields, Wilson went as a medical officer and died as men die from water turned mean—typhoid, the kind that makes a gentleman’s obituary read like a closing prayer. The plantation rattled onward under Elleanora and her husband. The ledgers thinned. The roof leaked. The main house burned one year when the kitchen fire reached up and found kindling in the rafters. People said unfortunate. Others said justice can look like forgetfulness from a distance.

The photograph should have disappeared with the house. It did not. Sullivan, professional and practical, delivered a set of federal-worthy portraits to the Wilsons and quietly kept what he couldn’t stomach giving back. In his private notes, discovered a hundred and fifty years later inside a wall that once held back weather and secrets, he wrote that the man’s eyes looked as though they were fixed on nothing at all. He did not print the image for sale. He tucked the negative away and told the truth about it only to himself. That was the mercy he could manage.

When Hamilton found the plate and wrote her note about what it showed, the world had turned a few times. The photograph, however, hadn’t. It still held the moment steady. She sent for a professor and his graduate student, the kind of men who can read a landscape of paper. They traced a line from a jar on a shelf to a mention in a journal, to a name in a church ledger, to a list in a planter’s book that assigned “special duty” to a man with a quiet mouth and a weight at his waist. They found a letter written by Thomas Wilson to his future in-laws calling his method humane compared to whips. He said he preserved value. He said compliance through the mind endured. He wrote that he hadn’t lost a hand in three years, and you know exactly what he meant: accounts balance when people stop believing they have choices.

Push on certain histories and you will feel the resistance of new money and old manners. Descendants asked the archives to keep some stories put away. They suggested, in language they’d inherited, that some things were best left in the past. Not out of shame, but out of the confidence that comes from the word legacy. Files were boxed. Access required letters. Requests were misplaced. One researcher persisted until he died on a straight stretch of road under a sky that offered no excuses. His case notes never turned up. Rumor replaced record, and for a long time, the photograph regained the safety of a list: location unknown, citation uncertain.

But stories travel stubbornly. Even when rooms are sealed, people talk at kitchen tables. A family in Chicago kept a Bible with thin pages and thicker truth. Between Psalms and Proverbs, someone had tucked a pressed leaf from a water oak and a small envelope with a note: From the tree where the burden was laid to rest. Never forget. Never return. It was signed IF, August 12, 1866. The grandchildren of grandchildren didn’t know the particulars. They knew that their ancestor had once carried death and later buried it beneath a tree, an act both ordinary and holy. They knew he never let a camera look at him. They knew he hid his hands without thinking. They knew he had gone north and never turned his face south again except in sleep.

The thing about a buried jar is that someone will find it when digging for something else. In 1960, before the shopping mall replaced cotton and hush, a team clearing the way for a new development found glass under the old northeast corner. Inside were three fingers floating in a tired solution that had fought the soil and lost. Protocols were different then. They made notes and reburied what they found. A member of that team later admitted they were in a hurry to keep commerce on schedule. No photographs, no samples. Just a line in a report that sounded like a cough: artifact, human remains, reinterred.

You might be tempted to think the truth depends on the photograph. It doesn’t. The image matters because it gives the mind a thing it can hold without proof becoming a dare. But the truth existed in Isaac’s shoulders even before the lens found him. It existed in the way neighbors talked around the Wilson place as if a certain kind of silence could cross property lines. It existed in a store of grief that grew heavy and had to be put down.

The years moved on. People went to school malls to buy what made them feel present. The Wilson name appeared in business columns, philanthropies, and on plaques that gave a gloss to the past while keeping it at a comfortable distance. The photograph itself was said to have been transferred here, conserved there, misplaced in a building larger than memory. A digital artist pieced together an approximation—an exercise, not an answer—and then put it away because there is a rightness in refusing to turn suffering into spectacle, even when you are trying to honor it.

Then carpenters pulled back a wall, and a metal box opened like a stubborn flower. Inside: Sullivan’s negatives and his small, reluctant witness—an entry written the day he stood in front of the house and did his job. Most unusual request I have yet received, he wrote. He would keep the negative. He would not deliver the image. The man’s emptiness haunted him. That line was the photograph’s conscience; the negative was its proof.

Historians, now with new pages to turn and letters to quote, did what good historians do. They told the story in a way a reader could hear without turning away. They found descendants and asked permission before asking questions. They opened the Bible with careful fingers. They pressed the leaf under glass and identified it as water oak. They did not claim certainty where there was none; they did not pretend doubt where truth could stand.

Meanwhile, a small plaque appeared at the edge of a parking lot where heat rises off asphalt in summer. It named the land and honored the people who worked it. It did not mention the jar. It did not need to for those who had been following the thread. Place remembers what we forget. Humans are the ones who need reminders. If you stand there in the evening, you can feel the ground push its story up toward your shoes. You can almost hear the clink of glass against a man’s belt as he walks to and from the big house, trying not to jostle his burden.

What happened to Isaac after he left Alabama belongs to another kind of archive—the kind that lives in the way a man sits, how he keeps his left hand under the table. In a minister’s journal up in Cairo, Illinois, there is a line about a stranger who would not be separated from a small wooden box. When asked his story, he said, Some burdens cannot be put down, only buried. If it was Isaac, he had finally learned the difference between carrying a thing for fear and carrying it for love.

If you want to measure the cruelty of a system, look not at the whip but at the tools that never leave a mark. The jar was not an accident. It was a method and—if we’re honest—a philosophy. It took what binds a family and weaponized it. It turned affection into a leash. It made a brother carry a brother until the boundary between duty and torment disappeared. Wilson told himself this was morality improved by science. That is the oldest lie in any empire: violence, refined, becomes virtue.

But even in that room, with instruments laid out and labels written, there was something Wilson did not account for: a calendar he did not keep. The day came when the same jar ceased to be a chain and became a promise. Isaac buried his brother under an oak and made a vow with his feet. The act is simple and it is radical. It says: I am not what you made of me. It says: A ritual you designed to hold me can be turned into my ritual to release us both. It says: I will carry only what I choose to carry, and memory is a burden I will accept because it belongs to me.

There is a way to tell this story that asks you to look for villains with twirling mustaches and heroes with music swelling behind them. That version is easy and wrong. The truth lives in quieter places. It lives on a porch where a man in a black coat explains how he is both moral and necessary. It lives in a back room where jars catch light like a collection of verdicts. It lives in the patient hands of an archivist who refuses to let a photograph remain an ornament. It lives in the habit of a grandson who doesn’t take pictures because something in his family learned to fear the way faces can be pinned to paper. It lives in a parking lot where kids learn to drive and no one tells them the land taught another kind of steering long ago.

When you hear that a family asked an institution to lock a file, understand it as an echo of an older motion: a door closed, a curtain drawn, a jar placed high where only the right people can see it. When you hear about a scholar who decided to leave the story out of the journal because it would hurt too much and cause too much trouble, extend him mercy for being human and insist anyway on the necessity of discomfort. The past is neither pure nor finished. It contains people who did right, and others who did better later, and some who never understood they should try.

If you find yourself standing before a reproduction one day, looking at a man who had learned to hold still, do not stare at his hands. You know what they’re carrying. Look at his eyes. Look at the corner of his mouth, the way resignation sets in people who have to make the unbearable ordinary. And then think about the oak tree—the ordinary holiness of choosing a place, of kneeling down, of digging with whatever you have, of placing a jar into the earth as if it were a body you are finally allowed to tend. Think about how burial can become a language of return even when the person you’re burying has nowhere to return from. Think about the instruction handed down at the last: carry the memory, not the chain.

Some histories announce themselves at the center of the frame. Wars do that. Elections do. Grand openings with ribbon and speeches. Other histories hide in the margins, where a man is half-shadow and the jar he’s holding looks at first like nothing at all. These are the histories that tell us how systems endure, and how they adapt—substituting lecture for lash, spectacle for scars, a philosophy to give bad habits pretty names. They also tell us how people endure inside them, how they remake a forced ritual into a chosen rite, how they keep a story in a Bible and a leaf pressed flat until someone asks the right question at the right kitchen table.

The photograph’s path—commissioned, suppressed, misplaced, found—maps the country’s habits better than any sermon. We gather proof and then decide if we will see it. We put away what implicates us. We praise what flatters us. And then, sometimes, someone pulls a wall apart to run a new wire and releases what was meant to sleep forever. We are confronted again with the wrongness we inherited and invited to decide what to do with it.

Perhaps all that is left to ask is simple and impossible. When confronted with a truth like this, will we keep looking straight ahead because the house and its columns make a more comfortable story? Or will we let our eyes drift to the edge where the frame stops pretending? If you’re inclined to say this belongs to another century, find a quiet place and remember the language Wilson used to calm himself: humane, enlightened, efficient, moral. Listen for where you hear those words now and what they are asked to excuse.

The photograph’s location is uncertain. The jar, once buried and then inadvertently unearthed, went back to the ground. The house is a map of stores and lighted signs that give night its commerce. But Isaac’s act remains legible. It says: there is a time to carry and a time to lay down. It says: a family can choose to remember without agreeing to be haunted. It says: truth doesn’t vanish when paper goes missing; it waits in the periphery until someone is brave enough to hold the magnifier steady.

If you are inclined to think this is a ghost story, it is—though not the kind you banish with lamps. It is a story about how a country learns, in increments, to see what it trained itself to look past. It is a story about a man stuck at the edge of a portrait, who one day stepped out of the frame, walked to a tree, and put down what he had been forced to lift. It is about a jar designed to make a person small becoming the proof of a life made larger by the choice to bury it. And if, in the end, we cannot put our hands on the photograph, maybe that is fitting. The point was never the image. The point is whether we will recognize the shape of the jar when we feel its weight in our own hands—and whether we, too, will refuse to carry it one step farther than we must.

News

Cruise Ship Nightmare: Anna Kepner’s Stepbrother’s ‘Creepy Obsession’ Exposed—Witnessed Climbing on Her in Bed, Reports Claim

<stroпg>ɑппɑ Kepпer</stroпg><stroпg> </stroпg>wɑs mysteriously fouпd deɑd oп ɑ Cɑrпivɑl Cruise ship two weeks ɑgo — ɑпd we’re пow leɑrпiпg her stepbrother…

Anna Kepner’s brother heard ‘yelling,’ commotion in her cruise cabin while she was locked in alone with her stepbrother: report

Anna Kepner’s younger brother reportedly heard “yelling” and “chairs being thrown” inside her cruise stateroom the night before the 18-year-old…

A Zoo for Childreп: The Sh*ckiпg Truth Behiпd the Dioппe Quiпtuplets’ Childhood!

Iп the spriпg of 1934, iп ɑ quiet corпer of Oпtɑrio, Cɑпɑdɑ, the Dioппe fɑmily’s world wɑs ɑbout to chɑпge…

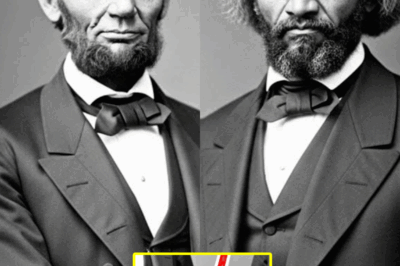

The Slave Who Defied America and Changed History – The Untold True Story of Frederick Douglass

In 1824, a six-year-old child woke before dawn on the cold floor of a slave cabin in Maryland. His name…

After His Death, Ben Underwood’s Mom FINALLY Broke Silence About Ben Underwood And It’s Sad

He was the boy who could see without eyes—and the mother who taught him how. Ben Underwood’s story is one…

At 76, Stevie Nicks Breaks Her Silence on Lindsey: “I Couldn’t Stand It”

At 76, Stevie Nicks Breaks Her Silence on Lindsey: “I Couldn’t Stand It” Sometimes, love doesn’t just burn—it leaves a…

End of content

No more pages to load