It starts with a voice that sounds like a brass band and a back-alley sermon rolled into one. A voice that struts. A voice that rhymes because prose can’t carry its weight. A voice that dares you to blink while it tap-dances on the edge of the stage and the edge of good sense. Dolomite is my name. I killed Monday, whooped Tuesday, and put Wednesday in the hospital. If you know, you grin; if you don’t, you lean in. That’s how Rudy Ray Moore always wanted it—lean closer, he’s got something to show you.

He was born Rudolph Frank Moore on March 17, 1927, in Fort Smith, Arkansas—a skinny kid with seven siblings, a church choir for an incubator, and a mother who believed in poems the way other families believed in fences. He watched his mother remarry, bounced briefly to Paris in Logan County, and came right back to Fort Smith, where Sunday mornings were gospel and Monday through Saturday belonged to survival. He had a cadence even then. People said he might grow up to be a preacher. He had the timing, the heat behind the words, the conviction that if he spoke it right, the room would both laugh and listen. He didn’t have a safety net. He had something better—momentum.

At fifteen, he packed a bag and rode faith north to Cleveland, Ohio. He peeled potatoes, scrubbed dishes, did everything but settle. Then one night, with quarters in his pocket and nerves steady enough to pass for cocky, he leaned against the wall at a talent show and thought, I can do that. Actually, I can do better than that. So he did. He began winning contests with a loose, hybrid act—singing, dancing, punchlines so blue they made the curtains blush. By seventeen, he was playing the Blue Flame Show Bar and the Moonglow nightclub, not as Rudy Ray Moore but as Prince Dore, a turbaned, exotic headliner who understood something before most entertainers did: people don’t just pay for material. They pay for a persona.

He wore the Prince like a cape until Uncle Sam called. The year was 1950. Twenty-three years old, drafted into the United States Army, sent to Germany, and—this is the part that surprises people who think of the military as the end of spontaneity—he got sharper. He joined an entertainment unit, tried out a character he called the Harlem Hillbilly, and found the sweet spot between music and mischief. He came back stateside in 1953 with a gift you can’t teach: instinct for when a room is ready to be pushed, and how far. He was a performer now, full stop. A weapon primed by applause, rejection, repetition, and the truth-telling oxygen of live crowds.

The next years were the Chitlin’ Circuit—the road houses, the smoky inner-city clubs, the carpet stained with spilled beer and laughter, the sort of rooms where your reputation lasted exactly one set at a time. These were the places polite society pretended didn’t exist. Rudy didn’t just exist there. He thrived. He danced. He crooned. He ran routines that rhymed and routines that didn’t, stories with a beat so hard they felt like drumlines. The comedy was filthy and free—unapologetically profane, insurgently sexual, and tuned precisely to the frequency of audiences that worked hard all week and came out to hear somebody say what everybody was thinking but nobody was allowed to say out loud.

He was building something in those clubs. Not just a niche, but a form. If you listen to his riffs from that era, you hear the bones of future genres—hard internal rhymes, punchline cadences, a call-and-response rhythm that pulled the crowd into the act until they felt like accomplices. That’s why people later called him the godfather of rap—not because he set out to invent anything, but because he mastered an approach: rhymed storytelling with a street-smart narrator who talked tough, bragged bigger, and lived like rhythm was the only law that mattered. He framed jokes like 16-bar verses. He was rat-a-tat and elastic. He took obscenity and transformed it from shock value to a language of joy.

Los Angeles found him behind a record store counter in the late 1960s, stocking vinyl and soaking up the neighborhood. Outside, on milk crates and stoops, men traded rhymed toasts—oral folklore that stretched back through decades of African American street poetry. Rico, a local character with a pocket full of swagger and breath like whiskey, told stories about a mythic hustler named Dolomite, a man who feared nothing and bowed to no one, who swaggered through danger like it was a parade thrown in his honor. Rudy listened. He didn’t steal; he did business. He bought Rico’s stories, paid for the fragments, and shaped them with his own delivery, his own theatricality, his own ear for the beat. He took the toast tradition and fed it the bass boost of his personality.

Dolomite was not a whisper. He was a shout. A blaxploitation Moses parting a Red Sea of censors and gatekeepers, marching into places he wasn’t allowed to go. When Rudy recorded Eat Out More Often in 1970—the first of his infamous “party records”—he knew exactly what he had. Major labels wouldn’t touch it. He pressed and sold it himself. He moved units hand to hand, trunk to living room to afterparty, an underground distribution network built on word of mouth and hustler stamina. He made more: This Ain’t No White Christmas, The Dirty Dozens, The Signifying Monkey. The albums were so explicit they made record executives clutch the pearls they pretended not to be wearing. The black audience—his audience—ate them up.

He was the king of party records, and he wore the crown the way he wore everything—loud. But he wanted more than bowls of laughter and stacks of cash in the back room of a club. He wanted the big screen. Hollywood did not want him back. That was not a barricade; it was an invitation. He raised his own money. He wrote the script. He hired friends. He performed his own stunts, which is not the same as recommending anyone else do it. In 1975, at forty-eight, he made Dolomite, a blazing, low-budget meteor with fight scenes that looked like they’d been choreographed by good intentions and adrenaline, dialogue so outrageous it wrapped around from bad to brilliant, and an attitude that made critics ball up their notes and gnash their teeth.

Urban theaters turned it into a hit anyway. The Fox in Detroit, the Woods in Chicago—big houses with big sound where audiences talked back at the screen like it was family. Dolomite wasn’t a film that requested permission to exist. It swaggered through the velvet rope and grabbed a seat. He followed up with The Human Tornado (1976), Petey Wheatstraw: The Devil’s Son-in-Law (1977), and Disco Godfather (1979), each one a fever-dream cocktail—part karate without a dojo, part sermon without a pulpit, part public service announcement shouted through a rhinestone megaphone. He told people to put something in their write-ups about angel dust because it was destroying the youth. He was a clown and a crusader, a showman and a scold. The contradictions weren’t bugs. They were the whole point. He was speaking to his people in a language that didn’t apologize for its volume.

So here we must talk about the man and the myth that wore each other like a skin. Dolomite—the character—was hypermasculine, a braggart and a ladies’ man, a pimp-adjacent superhero with a walking stick and lines that hit like uppercuts. Rudy Ray Moore—the person—was more complicated, which is another way of saying he was human. He never married. He had no children. For years, there were whispers. He heard them. He ignored them. He lived as he lived, private because the world he worked in didn’t grant privacy to men who didn’t fit its narrow windows. People close to him later acknowledged what he never packaged for public consumption: he loved differently than his stage persona suggested. He was, by many accounts, a closeted gay man through much of his career—navigating the strain of that secrecy while playing a character built on womanizing bravado. You can call that contradiction. Or you can call it the cost of doing business in a time that punished difference.

What matters for this story—what keeps it honest without being prurient—is that the art he made was both armor and passport. He built a character that could walk into any room and command it. He used that character to say things that polite people said couldn’t be said. He minted himself as an independent star in an industry that had no interest in financing his ambitions. And he did it all with a smile like a dare. Hollywood said no. He made it a challenge. He didn’t break in the front door; he built the back door. Then he brought everybody he could fit with him.

There’s a particular American genius in that kind of hustle, the bootstrap myth made real by sheer stubbornness. It also has a melancholy edge. Independent means you keep creative control. It also means you pay your own bills. Rudy poured his own money into projects he believed in because nobody else would. He distributed films independently because the big studios wouldn’t lift a finger unless it was to wag at him. He made millions laugh. He didn’t make millions of dollars. By the time he died in Akron, Ohio, on October 19, 2008, at eighty-one, after complications related to diabetes, his net worth estimates hovered in the low single-digit millions, depending on who you asked. For a man who had bent hip-hop, comedy, and indie cinema in his direction, it felt like the math didn’t add up.

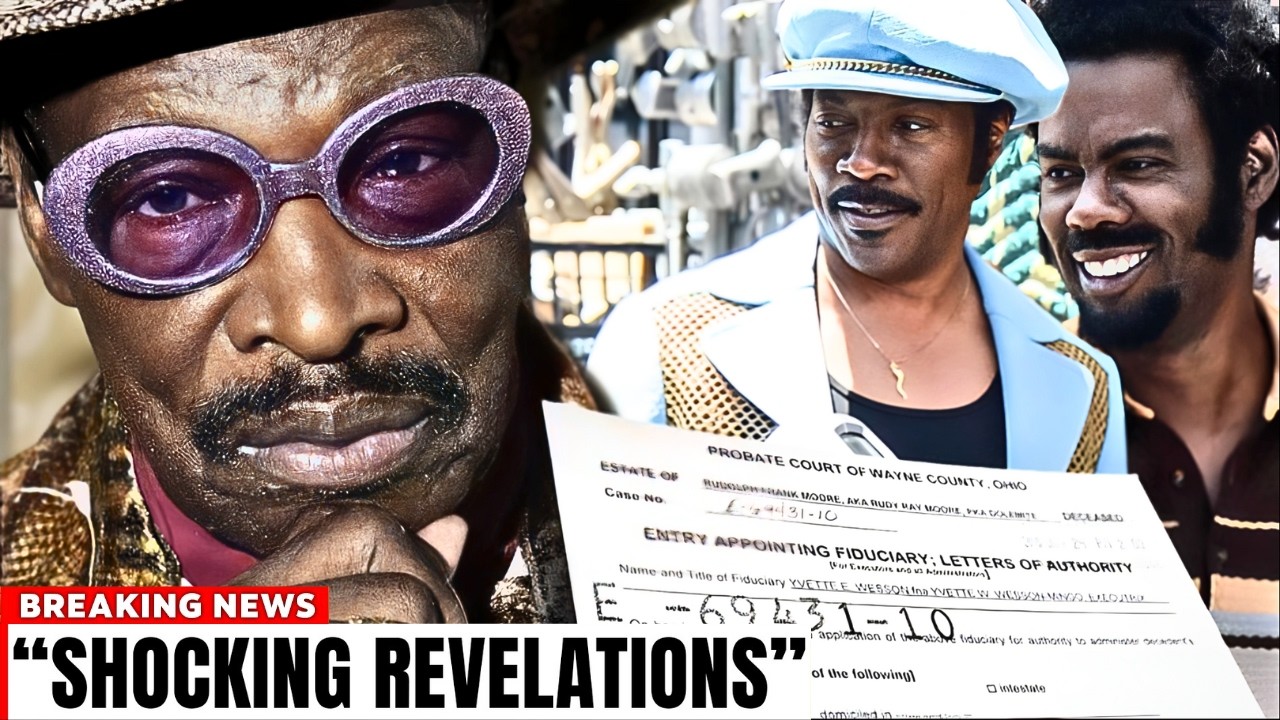

But stories don’t end just because a heartbeat does. In 2019, Eddie Murphy—who understands better than almost anyone alive how comedy and character can be passports—put on the suit, the smile, and the swagger and introduced a new generation to the blueprint with Dolomite Is My Name. The film didn’t sand down the rough edges. It didn’t turn the hustle into a fairy tale. It showed a man who believed in himself so fully he made belief a production budget. Murphy delivered Rudy’s audacity with affection, and critics who once laughed at Dolomite found themselves laughing with Rudy Ray Moore instead. His influence became visible again, like heat rising off asphalt. Rappers who had grown up on the cadence of dirty party records said his name out loud. Snoop Dogg, who learned the craft of rhythmic storytelling from elders who learned it from Moore’s records, called him the greatest of all time. Hip-hop historians nodded, because they’d been saying it quietly all along.

If you care about the roots of things—how a rhymed insult morphed into a verse, how a boasts-turned-bars cadence showed up decades later in the mouths of MCs—you can trace the line. Moore wasn’t the only pioneer, but he was a loud one. His records taught the lesson that would underpin a culture: if the mainstream can’t handle what you have to say, sell it to the people who can. He made content too explicit for broadcast standards and proved that audiences would vote with dollars and laughter. He took street-corner folklore and legitimized it by putting it on wax. His independent films—awkward, hilarious, messy, essential—proved you didn’t need a blessing from major studios to fill seats. He carved a lane that future artists would widen into a highway.

The temptation with figures like Moore is to turn them into magic tricks—now you see him, now you don’t; was he real, was it all a bit? But the truth is more interesting. He was a church kid who never lost his ear for preaching. He was a turban-wearing dancer who understood the power of costume. He was an army entertainer who learned to command hostile rooms with charm and rhythm. He was a record-store clerk who recognized a folk hero in a drunk’s poetry and built an empire out of it. He was the toughest talker in the club and a man whose private heart lived behind a lock he kept for good reasons. He was contradictory because people are. He was complicated because simple doesn’t survive long on those stages.

And he was funny—rooted-in-the-gut funny, the kind that makes you yelp and slap a table. He’d snap at a heckler and make it sound like a blessing. He’d stack a boast so tall it wobbled and still stick the landing. He’d wrap lessons into lines that were too filthy to teach anywhere else. That’s what the greats do. They smuggle truth into the joke. They make a room feel brave enough to hear it.

To keep a story like this captivating and credible—you have to honor the record. The facts are the spine: born in 1927 in Arkansas; Cleveland by his mid-teens; drafted and stationed in Germany; the Chitlin’ Circuit grind; the L.A. record store; the birth of Dolomite through toast tradition; Eat Out More Often and the party records; the independent film run from 1975 to 1979; the small fortune that never quite matched the giant footprint; the death in 2008; the legacy revived in 2019 by Eddie Murphy’s biopic. The rest is flesh: eyewitness accounts, interviews, documentary testimony about the life he lived when the lights were off and the audience went home. Rumors alone don’t make history. Corroboration does. The point is not to sanitize Rudy Ray Moore or to sensationalize him. It’s to tell the story he earned—a story that stands on what can be verified and breathes with what can be responsibly inferred from people who were there.

You can keep readers from hitting the report button the same way Rudy kept crowds from hitting the door: respect them. Don’t claim what you can’t back up. Don’t throw gasoline on speculation and pretend it’s a spotlight. Where the record speaks, quote it. Where the record is silent, say so. The truth here is plenty dramatic without decorations. A black entertainer in mid-century America clawed his way into the culture with nothing but nerve, rhythm, and the stubborn belief that if the door was locked, he could pick it with laughter. He invented a persona that let him shout what he couldn’t whisper. He showed rappers how to talk their talk. He showed indie filmmakers how to get it done without permission. He carried a secret that cost him. He died with less money than his legend would suggest. A decade later, a superstar put his name back in lights so the young and the uninitiated could see where so much of what they love came from.

There’s a moment in Dolomite Is My Name where Eddie Murphy’s Rudy, sweating and smiling and pushing the boulder up the hill yet again, says he’s going to show them. That’s the heartbeat of the whole saga. He kept showing them. He showed them you could build an audience without a co-sign. He showed them you could be so outrageous the critics choke on their adjectives and still pack theaters. He showed them you could rhyme filth into art, outrage into joy, jokes into blueprints.

And he showed them that you don’t have to be one thing. The church kid and the club king can be the same man. The preacher’s rhythm can preach sin and still feel like service. The private heart can be locked and the public persona open as the sky. Reinvention isn’t betrayal in America; it’s tradition. Rudy Ray Moore lived that tradition so hard he turned it into a monument with a microphone for a cornerstone.

If you’ve never seen Dolomite, you can watch it now and laugh for all the reasons audiences did in 1975—and also for a new one: the exhilaration of watching someone refuse to be told no. If you’ve never heard Eat Out More Often, you can hear the crackle of cheap vinyl and the roar of a live bar and a form of comedy that doubles as oral history. If you’ve never said his name with the respect he earned, now you can. It’s not worship. It’s credit.

He wanted the last word to be a punchline. The cosmos, as it often does, had other plans. Eddie Murphy delivered the last word instead, dressed in Rudy’s glitter, speaking Rudy’s gospel of audacity. The country listened. Maybe that’s the best ending an independent legend could hope for—that he told the truth the way he knew how, and the culture eventually caught up.

Dolomite is his name. Rapping and capping became everybody’s game. And somewhere, in a corner of a club where the lights never quite go all the way up, Rudy Ray Moore is still grinning, still daring you to lean in closer, still promising to show you. Because he always did. Because he always will, as long as the records spin and the stories keep their beat.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load