In the heart of Alaska, where the spruce trees crowd close and the sky stretches endlessly, the Fandel family cabin stood as a quiet witness to a mystery that has haunted the Kenai Peninsula for nearly half a century. It was a place where the wind carried the scent of pine and the hum of distant engines from the highway, a place so secluded that most folks in Sterling, population less than 900 in the late 1970s, only knew about it because of the children who lived there—Scott Curtis Fandel and his little sister, Amy Lee.

Scott was thirteen, tall for his age, smart and protective—a boy who, according to everyone who knew him, would never let harm come to his sister if he could help it. Amy was eight, sweet and beautiful, with a smile that lit up the classroom and a quiet bravery that belied her years. Their mother, Margaret, worked long hours as a waitress, struggling to keep the family afloat after Amy’s father, Roger, left for Arizona in the spring of 1978. It was a hard time, but the Fandel kids were resilient, finding joy in small things, like playing with the neighbor’s children or sharing a box of macaroni and cheese in the kitchen.

September 5th, 1978, was supposed to be a fresh start. Margaret’s sister Cathy had just moved in from Illinois, and the family celebrated with dinner at the cabin. Afterwards, the four of them drove out to Good Time Charlie’s, a bar-restaurant on the Sterling Highway, where the kids played video games and sipped Coca-Colas while the adults chatted over drinks. It was getting late, so Margaret and Cathy drove Scott and Amy back to the cabin, reminding them not to stay up too late and—almost jokingly—to lock the front door. The lock was broken, but in those days, few people worried about such things. The woods felt safe, and the darkness was just another part of life.

After their mother and aunt left to continue their night at the bar, Scott and Amy didn’t go straight to bed. Instead, they wandered over to the Lepton family’s quonset hut, just two hundred yards away, to play with the five neighborhood kids. Nancy Leon, the Lepton mother, remembered them being in great spirits, excited about their aunt’s arrival. Eventually, the noise got to be too much, and she sent them home, probably close to midnight.

A neighbor driving by around 11:45 p.m. noticed the cabin lights burning—nothing unusual, since Scott and Amy were both afraid of the dark and always left the lights on. But when Margaret and Cathy returned between 2 and 3 a.m., the cabin was dark and quiet. Inside, a half-made meal sat on the counter: a box of macaroni and cheese, an open can of tomatoes, a pot of boiling water. It was the kids’ favorite. Margaret didn’t think much of it; she assumed Scott and Amy had gone back to the Leptons’ and fallen asleep. She didn’t check their rooms or ask the neighbors. The two women went to bed, perhaps dulled by drink and the late hour, trusting in the safety of the woods and the routine of small-town life.

The next morning, Margaret left for work around 8:30 without checking on her children. Cathy woke up around noon, noticed the kids weren’t home, and figured they were at school. It wasn’t until Margaret called Amy’s school to pass on a message that she learned Amy hadn’t shown up. The alarm bells finally rang, but Margaret’s boss wouldn’t let her leave work. The school bus came and went, but neither child appeared. The Lepton kids stopped by to play and told Cathy they hadn’t seen Scott or Amy at school, nor had they slept over.

Now, panic set in. Cathy called Margaret, who called the Alaska State Troopers at 5:14 p.m.—nearly 17 hours after the children were last seen. The search began immediately, but the only clues were a couple of bullet casings found outside the cabin. No one could say if they were old or new. Volunteers scoured the woods, troopers brought in search dogs from Anchorage, but the forest swallowed all traces. The cabin’s location, set back from the road and shrouded by trees, made it difficult for anyone to know the children were alone unless they’d been watching.

Theories swirled. Had Scott and Amy wandered off, despite their fear of the dark? Had someone broken in through the unlocked door? Was it a planned abduction, or a crime of opportunity? The Lepton family hadn’t heard any screams or gunshots that night. The bullet casings might have been old, or perhaps a silencer was used. Margaret tried to reach Roger in Arizona, suspecting he’d taken the children, but his relatives hadn’t seen them and he quickly flew to Alaska to help with the search. Investigators checked ferries leaving Homer and alerted the Canadian Mounties to watch for children crossing the border.

Sterling was in the midst of an oil boom, bringing transient workers to town. Could someone at the bar have overheard Margaret and Cathy’s plans, realized the kids would be alone, and followed them home? Or was it the carnival workers who Margaret had let crash at her place in late August? A witness reported seeing a black sedan speeding away from the cabin road on the night of the disappearance. The car belonged to two carnival workers from the East Coast, and a trooper tracked them to Maryland. They admitted being near the cabin, but their alibis checked out—the witness may have seen their car the night after the kids vanished.

The investigation was exhaustive. Troopers chased down hundreds of leads, but every path ended in frustration. Former trooper Tom Sumi described the search as “quirks and spiderwebs,” never getting closer to the truth. The family fractured under the strain. Roger accused his uncle Herman of killing the kids; Herman accused Roger. Police dug up Herman’s yard, but found nothing. Theories persisted: Scott was killed immediately after the abduction, Amy taken to California, Montana, or hidden somewhere in Alaska. But there was no evidence, no bodies, no answers.

Margaret eventually moved back to Illinois, hounded by blame and grief. She spiraled into depression and alcoholism, tormented by what-ifs and the relentless whispers of psychics. Over time, she found some peace—she quit drinking, remarried, and in 1988, told interviewers she still hoped her children would return. Roger, less hopeful, believed Scott would have contacted him if he were alive.

The details that remain are haunting. The kids returned from the Leptons’, began making food, and something interrupted them. Was someone hiding in the cabin, waiting for them to come home? Did an intruder slip in through the unlocked door while they cooked? The house showed no signs of struggle, no blood, just those bullet casings and the eerie silence of the forest. It seemed the children were taken quickly, quietly, and the perpetrator turned off all the lights before leaving. Maybe there was more than one person; maybe the kids were tied up, led away into the dark. The lack of evidence suggests they were kidnapped alive, their fate decided elsewhere.

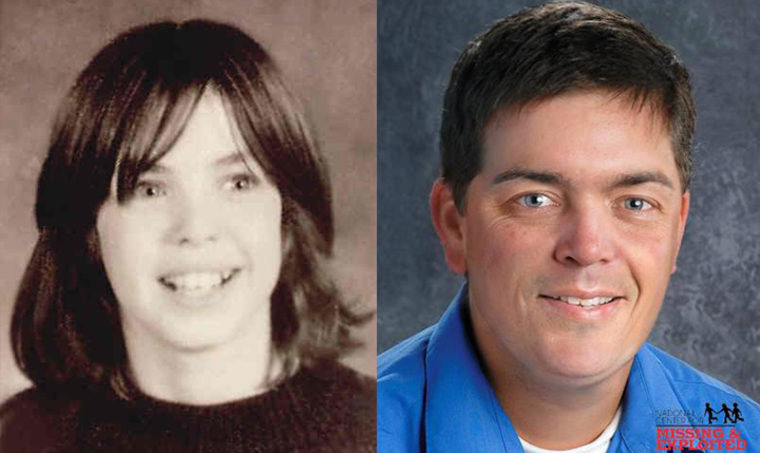

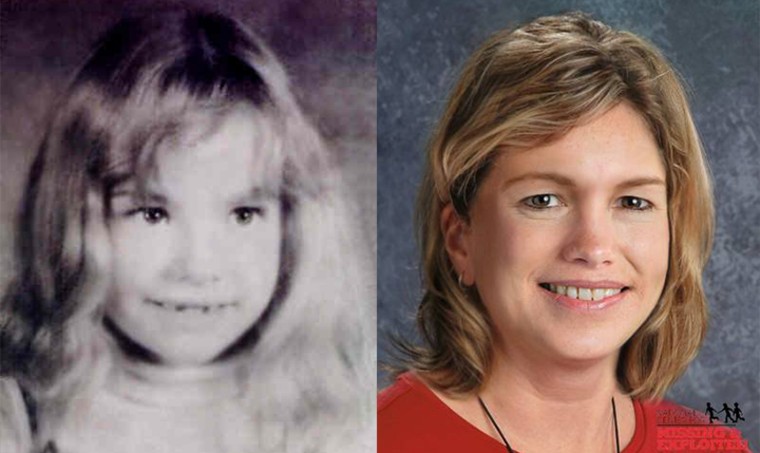

There are age progression photos now, showing how Scott and Amy might look as adults. Amy was four feet tall, fifty-two pounds, with blonde hair and brown eyes, last seen in a red turtleneck, striped vest, jeans, green socks, blue tennis shoes or tan Mary Janes, and a matching ring and necklace. Scott was four-foot-eleven, seventy-four pounds, brown hair, blue eyes, wearing a white polo shirt, jeans, brown sneakers, and known to carry rocks in his jacket pocket and possibly a folding knife.

Decades have passed, and the case has faded from headlines. There’s little coverage, few newspaper articles, almost as if the children have been forgotten. But for those who remember, the pain is fresh, the questions unresolved. How could two children vanish without a trace? Who would have known they were alone in that cabin? Was it a stranger, a neighbor, someone passing through? Could they still be alive, held captive somewhere, waiting to be found?

The woods of Sterling hold their secrets close. The Fandel cabin, if it still stands, is just another shadow among the trees. But Scott and Amy’s story is more than a cold case—it’s a reminder of the fragility of safety, the importance of vigilance, and the enduring hope that the missing will one day return. It’s a story that deserves to be told, shared, and remembered.

If you know anything—if you saw something, heard a rumor, or recognize their faces—please speak up. These children have been missing for far too long. Share their story, their flyers, their names. Every child deserves to be found, every family deserves answers.

Lock your windows and doors. Take care of each other. And never forget Scott and Amy Fandel, lost in the Alaskan night, waiting for the world to remember.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load