In 1824, a six-year-old child woke before dawn on the cold floor of a slave cabin in Maryland. His name was Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey—a name he would later change to Frederick Douglass, erasing the past and forging a new future. But even as a child, Frederick carried a secret: he was the son of a white man, almost certainly the plantation owner himself. The man who owned his mother. The man who, by law, also owned him.

This brutal truth—born from the institutionalized violence of slavery—would shape Frederick’s life in ways even he could not predict. Being the son of a slave master and an enslaved woman brought him no privilege; if anything, it made him a living threat, a testimony to the hypocrisy and cruelty that sustained the American slave system. Mixed-race children like Frederick were both proof of white men’s power and their moral bankruptcy—evidence that could not be spoken, shame that had to be hidden in plain sight.

Frederick’s earliest memories were marked by absence and longing. His mother, Harriet Bailey, was forced to work on neighboring farms. He saw her only a few times a year, when she would walk miles at night after a day of forced labor, just to hold him for a few hours before dawn. If she didn’t return in time, she would be whipped. These nighttime visits were acts of desperate love—defying exhaustion and the threat of violence for a few precious moments together.

But Frederick wrote in his memoirs that he had no clear affectionate memories of his mother. She died when he was about seven, and he learned of her death as if she were a stranger. Slavery didn’t just steal bodies; it stole families, memories, and basic human bonds. The system was designed to prevent love, to sever connections, to ensure that enslaved people could never form the relationships that might give them the strength to resist.

The question of paternity was even darker. Frederick bitterly described the common practice of white masters raping enslaved women, then enslaving their own children. Mixed-race children often faced even harsher treatment than others, as their very existence was a silent accusation against the system. They were resented by white women as evidence of their husbands’ infidelity, and despised by white men for reminding them of their own moral failures.

In his first autobiography, Douglass wrote plainly: “Slavery is terrible for men, but it is far more terrible for women.” He understood that enslaved women faced a unique horror—not only the violence of forced labor, but the constant threat of sexual assault, the agony of bearing children who would be enslaved, and the impossibility of protecting their daughters from the same fate.

Frederick was separated from his mother as an infant, raised by his grandmother Betsy Bailey in a small cabin away from the big house. There he lived in relative freedom until age six, playing barefoot with other enslaved children, not yet understanding the full weight of the chains that awaited him. But everything changed in 1824, when he was torn away without warning and delivered to the Y plantation, property of Colonel Edward Lloyd, one of the wealthiest men in Maryland.

It was there that Frederick first saw the true face of slavery—men and women whipped until their flesh opened, children torn from their mothers’ arms, hunger and exhaustion everywhere. The plantation was a small kingdom of terror, ruled with absolute power. One image remained forever etched in his memory: Aunt Hester, tied by her hands to a hook in the ceiling and brutally whipped by Aaron Anthony, the overseer. Frederick, hidden in a closet, witnessed everything. He was only six or seven, and the screams, the blood, the rhythmic crack of the whip against flesh became his introduction to the world he inhabited.

Years later, he wrote, “It was the bloodstained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery through which I was about to pass. It struck me with awful force. It was a most terrible spectacle.”

But even in these darkest moments, something set Frederick apart: voracious curiosity. He observed everything, memorized faces and names, paid attention to the conversations of white people. Curiosity was dangerous for an enslaved boy; questions could be interpreted as challenges to authority. Intelligence in a slave was not a gift to be cultivated, but a threat to be suppressed. Yet Frederick’s mind was too active, too hungry for knowledge, too unwilling to accept the boundaries slavery tried to impose.

At eight, Frederick was sent to Baltimore to serve in the house of Hugh Auld and his wife Sophia—a change that saved his life. Baltimore was a different world, where the cruelties of slavery were somewhat softened by urban proximity and the watchful eyes of neighbors. Sophia Auld had never owned slaves before and initially treated Frederick with something close to kindness. She saw him not as property, but as a human child, and this simple recognition changed everything.

She did something that altered the entire trajectory of his life: she began teaching him to read. She showed him letters, helped him spell simple words. Frederick absorbed everything like a sponge, his quick mind seizing on this new knowledge with fierce determination. For the first time, words revealed themselves as containers of meaning, of ideas, of power.

But when Hugh Auld discovered what his wife was doing, he was furious. In a revealing outburst, he told her, “If you teach that [boy] to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable and of no value to us. Learning would spoil the best [boy] in the world. If you teach him how to read, he’ll want to know how to write, and this accomplished, he’ll be running away with himself.”

Frederick overheard everything. In that moment, he had an epiphany: “I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty—to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement and I praised it highly. From that moment I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.”

Hugh Auld had accidentally revealed the secret that slaveholders guarded most carefully: education was the antidote to slavery. Knowledge was power. If reading would unfit him to be a slave, then reading was exactly what he needed to pursue with every fiber of his being.

From that moment forward, every opportunity to learn became a covert act of rebellion. Frederick began trading pieces of bread with poor white boys on the streets in exchange for reading lessons. They taught him letters and words in exchange for food. He stole old newspapers from trash heaps and read them in secret. He copied letters from fences and signs, tracing them with his finger in the dirt. He studied in secret, always afraid of being discovered, always aware that what he was doing was considered dangerous and subversive.

At twelve, he managed to secretly buy a book with fifty cents he had saved—a collection called The Columbian Orator. The book became his Bible, his window into a world of ideas that slavery had tried to keep hidden. It contained speeches about liberty, democracy, human rights, and the natural equality of all people. It included a dialogue between a master and a slave in which the slave systematically dismantled every argument for slavery, and the master, unable to refute his logic, freed him.

Frederick memorized entire passages. He learned rhetoric, argumentation, and eloquence. He discovered that words could be weapons more powerful than any physical force, that ideas could break chains that iron could not. Most importantly, he learned that slavery was a moral monstrosity that could be fought with words. The book gave him a vocabulary for the injustice he experienced daily—a framework for understanding that what he suffered was not natural or inevitable, but a choice that human beings made and could unmake.

Every page confirmed what he had begun to suspect: he was not inferior, his bondage was not justified, and the system that held him was built on lies.

At fifteen, Frederick was returned to the countryside. His behavior in Baltimore had become problematic for the Aulds: he was too confident, too well-spoken, too aware of his own worth. He asked questions, looked white people in the eye, and carried himself with a dignity considered inappropriate for a slave. So they sent him back to rural Maryland, hoping that hard field labor would break the spirit education had awakened.

He was sent to work under several different masters, experiencing again the brutality of plantation life. But in 1834, at sixteen, he was hired out to Edward Covey—a man with a sinister reputation as a “slave breaker.” Covey’s job was to destroy the will of rebellious enslaved people, to transform them into docile, obedient workers. His method was simple and brutal: constant physical violence, exhausting work without rest, and systematic psychological humiliation.

During the first six months under Covey, Frederick was whipped almost every day. Sometimes with a whip, sometimes with oak sticks, sometimes with whatever implement was at hand. Covey beat him for any reason, or no reason at all—simply to remind him of his powerlessness. Frederick bled, could barely walk, lost weight rapidly, and his hands became covered with blisters that broke and bled. His back was a map of scars.

He described this period as the darkest of his life, when he almost completely lost hope and seriously considered suicide as preferable to continued suffering. On one occasion, Covey beat him so hard that Frederick fainted from exhaustion and pain, collapsing in the field under the scorching sun. When he woke up, he tried to return to work but collapsed again. Covey found him lying in the field and kicked him violently in the side of the head, opening a wound that bled profusely.

In that moment, something inside Frederick broke—not his resistance, but his fear. He realized he could endure no more, that continuing to submit meant death anyway, and that he might as well die fighting than live on his knees. He made a desperate decision: he ran away from Covey’s farm and walked seven miles through the woods to the plantation where his legal master, Thomas Auld, lived. He hoped Auld, seeing his condition, would take him back or hire him out to someone else. But Auld was unmoved, telling Frederick he deserved the treatment he was getting and must return immediately or face even worse consequences.

On an August morning in 1834, shortly after his return, Covey tried to tie Frederick up for another whipping. But this time, Frederick fought back. He grabbed Covey by the throat. The overseer’s eyes widened in shock—no slave had ever dared to touch him in resistance. They fought hand-to-hand in the barn for nearly two hours. Covey called for help, but the cousin refused to get involved, and the enslaved men moved slowly, clearly hoping Frederick would win.

Frederick held his ground, fighting with every ounce of strength he possessed. He won—not by beating Covey into submission, but by forcing him to give up and walk away. The “slave breaker” had been unable to break this particular slave. Covey, humiliated, never touched Frederick again for the remaining six months of his hire. Perhaps he feared another fight, or perhaps he recognized something in Frederick’s eyes that he could not break.

Frederick would never be the same. He wrote later, “It was a glorious resurrection from the tomb of slavery to the heaven of freedom. My long crushed spirit rose. Cowardice departed. Bold defiance took its place. I felt as I never felt before. It was a turning point in my career as a slave. I had reached the point where I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman, in fact, while I remained a slave in form.”

During the following years, Frederick worked under less brutal masters, but the seed of freedom had already germinated and taken deep root in his soul. He began planning an escape, thinking through every detail and considering every risk. In 1836, with a group of other enslaved men, he organized an escape attempt. The plan was to steal a boat and row up the Chesapeake Bay toward Pennsylvania and freedom. But they were betrayed, captured before they could begin their journey. A mob descended on them with ropes and guns. Frederick was seized, bound, and nearly lynched by an enraged crowd who saw his education and eloquence as particularly dangerous.

He was imprisoned, expecting at any moment to be sold to the brutal plantations of the Deep South—a fate considered a death sentence. But Thomas Auld, for reasons Frederick never fully understood, decided not to sell him south. Instead, he sent him back to Baltimore, where Frederick returned to work as a caulker in the shipyards, learning a skilled trade that would prove crucial to his eventual escape.

In Baltimore, Frederick met Anna Murray, a free black woman who worked as a domestic servant. Anna was remarkable—strong-willed, independent, and brave enough to help an enslaved man escape, despite enormous risks. She became Frederick’s partner in planning his escape, providing not just emotional support, but practical assistance that would prove essential.

On September 3rd, 1838, Frederick executed the boldest plan of his life. He borrowed identification papers from a free black sailor, dressed as a sailor, and boarded a train at Baltimore headed north. The journey was fraught with danger—conductors checked papers, slave catchers patrolled the trains, any passenger could denounce him. At each stop, the fear of being discovered was suffocating. But he arrived in Philadelphia, and from there traveled to New York. When he finally stepped onto free soil, he fell to his knees and wept. The relief was overwhelming.

Years later, he described that moment: “A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath and the quick round of blood, I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life.”

But freedom came with immediate challenges. New York in 1838 was not safe for fugitive slaves. Frederick sought help from the black community and was directed to David Ruggles, an activist who helped fugitive slaves. Anna soon joined him, bringing money she had saved and possessions she had sold to finance their future together. On September 15th, just twelve days after his escape, they were married.

From New York, they traveled to New Bedford, Massachusetts, a whaling port city known as a relatively safe haven for fugitive slaves. There, Frederick took the name Douglass, chosen from a character in Sir Walter Scott’s poem, The Lady of the Lake, abandoning the surname Bailey that connected him to his enslaved past. Frederick Douglass had been born—not just as a name, but as a new identity, a free man who would speak for those still in chains.

In New Bedford, Douglass encountered a thriving free black community and a strong abolitionist movement. He attended meetings of the anti-slavery society and read William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, with intense interest. For the first time, he heard the institution of slavery denounced publicly and forcefully.

In August 1841, Douglass attended an anti-slavery convention in Nantucket. He went as an observer, not intending to speak, but William C. Coffin, who had heard Douglass speak at a black church gathering, urged him to share his story. Reluctantly, Douglass agreed. He rose to speak before a predominantly white audience, his hands trembling, his voice initially weak and uncertain. But as he began to tell his story, something transformed. His voice grew stronger, his words more powerful. He spoke from the heart, from experience, with an authenticity no theoretical abolitionist could match.

William Lloyd Garrison, the most famous abolitionist in America, was present. After hearing Douglass speak, he rose and gave an impassioned speech, pointing to Douglass and shouting to the crowd, “Have you ever seen a slave? This is a slave. Will you allow him to be dragged back into bondage?” The audience responded with thunderous shouts of, “No, no, never.”

Douglass was immediately hired by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society as a lecturer. His job was to travel throughout the North, telling his story and arguing against slavery. It was dangerous work; anti-abolitionist mobs frequently attacked speakers, and Douglass faced particular hostility as a black man who dared to speak publicly to white audiences. But he threw himself into the work with passionate commitment.

For years, Douglass traveled constantly, sometimes delivering dozens of speeches per month. He developed into one of the most powerful orators in America, combining personal testimony with sophisticated philosophical and moral arguments. But as his fame increased, many whites refused to believe he had been a slave—his eloquence became evidence against him. People accused him of being a fraud, a free black man pretending to be a fugitive slave to advance the abolitionist cause.

To prove his authenticity, Douglass made a decision both brave and dangerous: in 1845, he published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. The book provided detailed, specific information about his life in slavery—names, places, dates, events that could be verified. It was written with literary power that rivaled any American autobiography of the era.

The book was an immediate success, but it also made him legally identifiable as the fugitive slave Frederick Bailey. His former owner, Thomas Auld, now knew exactly where Douglass was and what he was doing. Under the fugitive slave law, Auld had every legal right to have Douglass captured and forcibly returned to Maryland.

Friends and advisers urged him to leave the country immediately. In August 1845, Douglass boarded a ship bound for England. It wasn’t a tour or an adventure—it was flight, escape from the land of his birth, because that land offered him no safety or legal protection.

The reception in England, Ireland, and Scotland was transformative. In Britain, Douglass experienced for the first time what it felt like to be treated as a full human being, regardless of his race. He was invited to speak to immense audiences, dined with members of parliament, stayed in hotels, and traveled in first-class railway carriages. The contrast was stunning and painful. In Britain, he was treated with respect and dignity; in America, he was legally property.

But even as he enjoyed his freedom and celebrity in Britain, Douglass was tormented by the irony. He was free abroad, but a prisoner if he returned home. British friends and supporters organized a campaign to solve the problem legally. They raised $710—a substantial sum—and negotiated with Thomas Auld to purchase Douglass’s freedom. Douglass was deeply conflicted about accepting this arrangement. On principle, it was repugnant, but pragmatically, he recognized that refusing meant permanent exile. After much agonizing, he accepted. On December 5th, 1846, legal manumission papers were finalized.

In April 1847, Douglass returned to the United States, no longer a fugitive but a free man. British supporters also raised funds to help him establish his own newspaper. On December 3rd, 1847, in Rochester, New York, the first issue of The North Star was published. Douglass served as editor and writer, giving him control over his message and his image.

As his fame and influence grew, so did personal attacks and scandals. Douglass maintained close working relationships with several white women abolitionists, most notably Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing. Racist newspapers seized on these relationships, publishing crude caricatures and accusing him of adultery. The attacks were designed to discredit him morally and sow division. Anna Douglass suffered these attacks in silence, having married Frederick when he was a fugitive with nothing, borne and raised five children largely alone while he traveled for months at a time.

Douglass never publicly addressed the specific allegations, maintaining that interracial friendship and collaboration were essential to the abolitionist cause, and that accusations of impropriety were rooted in racist assumptions. But the silence came at a cost, creating tension in his marriage and distance from some black leaders.

In 1859, the radical abolitionist John Brown approached Douglass with a plan to raid the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, arm enslaved people, and trigger a massive slave insurrection. Brown wanted Douglass as an ally. Douglass listened carefully but ultimately refused to participate, believing Brown’s plan was suicidal and would fail militarily, turning public opinion against abolitionists. Brown pleaded, but Douglass remained firm.

In October 1859, Brown executed his plan. The raid failed, Brown was captured and hanged, and the South erupted in hysteria. Douglass was implicated; authorities found letters from him among Brown’s possessions, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. Douglass fled to England again, defending Brown’s intentions but maintaining that he had been right to refuse participation.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Douglass saw it as the moment he had been preparing for all his adult life. He argued that the war must become a war to end slavery, not merely to preserve the Union. Through his newspaper, speeches, and writings, Douglass hammered this message relentlessly, urging that enslaved people be armed and allowed to fight for their freedom.

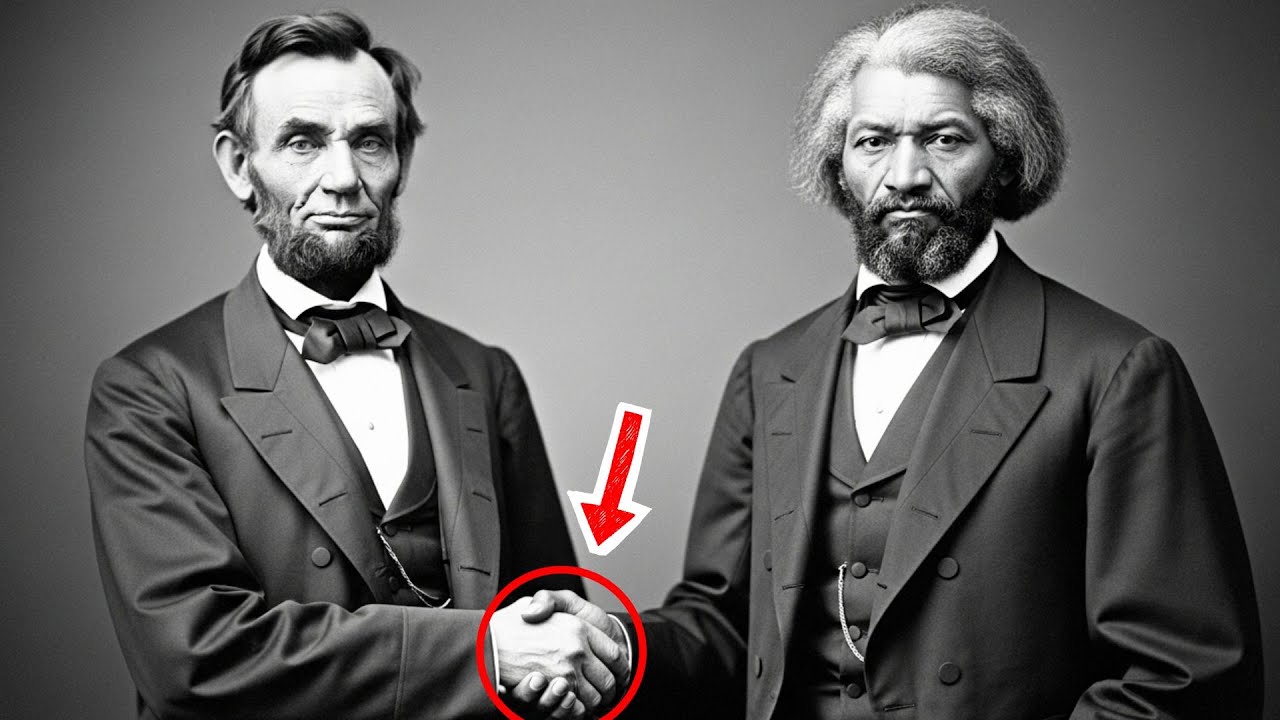

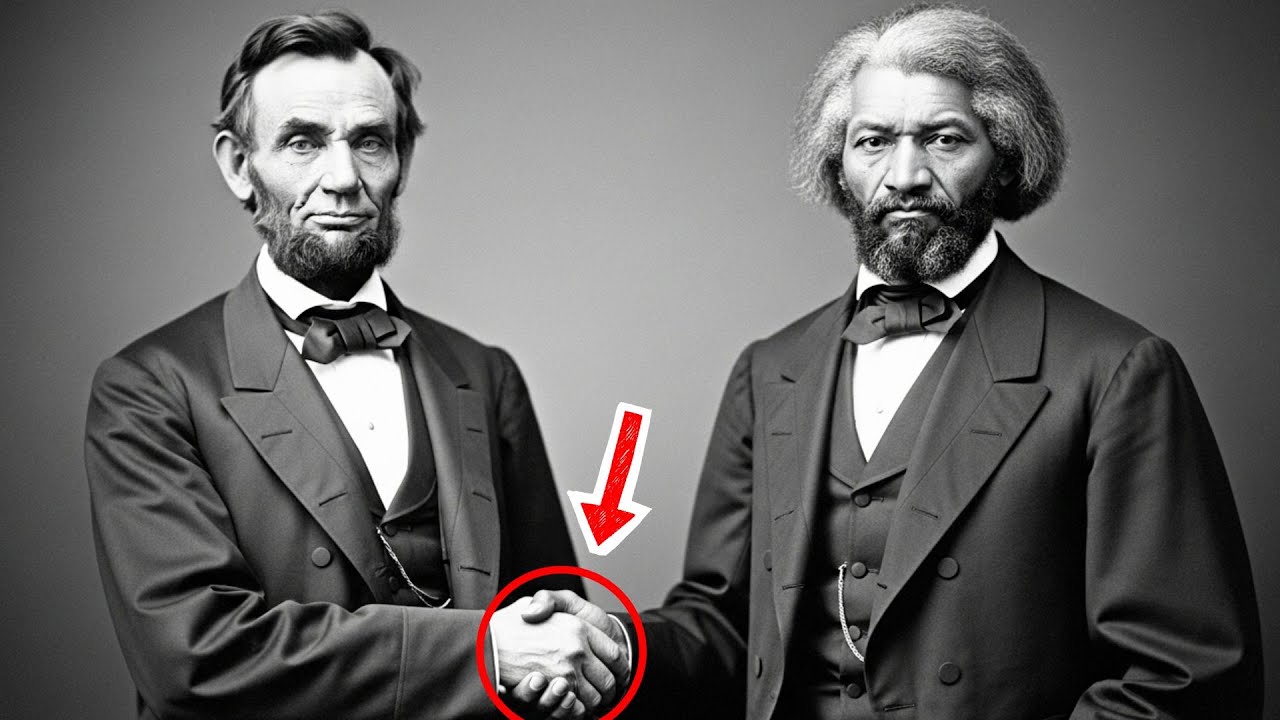

On January 1st, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Douglass celebrated it as a crucial step, while pushing for complete abolition. He recruited black soldiers for the Union, including his own sons. But promises were broken—black soldiers were paid less, received inferior equipment, and faced execution or re-enslavement if captured. Douglass demanded a meeting with Lincoln, insisting on equal pay and treatment. Lincoln listened, explained his constraints, and made vague promises. Douglass resumed recruiting, arguing that black men needed to fight for their own freedom.

The Civil War ended in 1865 with Confederate surrender. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States. But victory was bittersweet and incomplete. Southern states implemented Black Codes, restricting the freedom of formerly enslaved people. Violence exploded, and the Ku Klux Klan emerged. Douglass traveled through the South, horrified by what he found. White southerners were systematically rebuilding slavery in everything but name.

Douglass threw himself into the fight for Reconstruction, arguing for voting rights, land redistribution, education, and federal protection for freed people. He supported the 14th and 15th Amendments, granting citizenship and voting rights. He gave hundreds of speeches demanding genuine social transformation.

But he also faced bitter conflicts with former allies. The women’s suffrage movement split over the 15th Amendment, granting voting rights to black men but not women. Douglass argued that black men faced immediate threats of violence and needed political power urgently, while white women, however disadvantaged, at least had the protection of their race. This position damaged his relationships with some suffragist leaders.

Anna Murray Douglass died in August 1882, after forty-four years of marriage. She had been Frederick’s anchor, the stable center as he became a public figure. Their relationship was complicated, but real and important. After a period of mourning, Frederick felt something like liberation. In January 1884, he shocked the nation by marrying Helen Pitts, a white woman from an abolitionist family. The reaction was explosive. Racist whites attacked, and what hurt Douglass more was the reaction from much of the black community, including his own children.

Douglass responded with defiance: “My first wife was the color of my mother, and the second the color of my father.” He refused to apologize or justify his choice, arguing that genuine racial equality required breaking down barriers of all kinds. Helen proved to be an ideal partner, sharing his intellectual interests and engaging in political discussions as an equal.

During his final decades, Douglass held several prestigious government appointments, including US Marshal for the District of Columbia and US Minister to Haiti. Each appointment came with indignities and disappointments, revealing how incomplete racial progress remained. He witnessed the systematic destruction of Reconstruction’s gains, disenfranchisement, and the epidemic of lynching in the South.

Douglass spoke out repeatedly against lynching, demanding federal intervention, but his protests went largely unheeded. The North had lost interest in protecting black southerners, and the South reasserted white supremacy. The promise of equality was dying.

In his final years, Douglass’s speeches took on a tone of warning and urgency. He could see that America was betraying the principles he had fought for. “We have been grievously wounded in the House of our friends,” he declared after the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875. He warned that racial injustice would poison American democracy for generations.

On February 20th, 1895, Frederick Douglass woke in his home at Cedar Hill in Washington, D.C. He attended the National Council of Women Convention, greeted warmly by old friends. That evening, he returned home, animated and engaged, recounting the day’s events to Helen. Suddenly, he collapsed from a massive heart attack and died in mid-sentence, still engaged with the world until the very last moment.

His funeral was attended by thousands, tributes pouring in from across the country and the world. For black Americans and progressive whites, he was a hero without equal—a man who had risen from slavery to become one of the greatest Americans of any era. His life was proof of black people’s capabilities and humanity, a rebuke to every racist assumption.

Frederick Douglass died without seeing the racial justice he had dedicated his life to achieving. He lived to see slavery abolished, but not white supremacy destroyed. His predictions about America’s racial future proved devastatingly accurate. The decades after his death brought intensified segregation, disenfranchisement, and violence against black Americans.

But Douglass’s legacy remains complex and powerful. As a writer, he produced some of the most powerful prose of the 19th century. As an orator, he was perhaps unequaled, combining passionate delivery with sophisticated argumentation. As an activist and political thinker, he developed a philosophy of social change that combined moral persuasion, political engagement, and unwavering principles.

Above all, Frederick Douglass proved something fundamentally important: that human beings cannot be permanently reduced to property, that intelligence and dignity cannot be bred out or beaten out of people, that one person with courage and eloquence can change the terms of public debate and move the arc of history. He proved that a man born as cattle could become a moral giant, that someone denied education could become one of his era’s greatest intellectuals, that the son of a slave woman could stand as an equal with presidents and prime ministers.

He demonstrated that freedom is not a gift but a conquest, that justice is not inevitable but must be fought for in every generation, that progress requires constant vigilance and renewed commitment. His most famous words remain a challenge and an inspiration: “If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

Frederick Douglass was born the property of another human being—a thing to be bought and sold. He died Frederick Douglass, legally free, internationally famous, one of the most important Americans of the 19th century. The distance he traveled from slave cabin to the White House, from illiteracy to literary greatness, from powerlessness to moral authority was vast, almost beyond comprehension.

His life proved that even in the deepest darkness of injustice and oppression, the human spirit cannot be completely extinguished. That even when systems of power try to reduce people to things, humanity persists. That words and ideas can be more powerful than whips and chains. That one person armed with courage and eloquence and an unwavering commitment to justice can change the world.

The America that Frederick Douglass helped build remains unfinished. The struggle he waged continues in different forms, but every barrier broken, every right secured, every voice raised against injustice is part of his legacy. He taught us that freedom is a verb, not a noun—something you do, not something you have. He showed us that dignity cannot be granted or taken away, but can only be claimed and defended. He demonstrated that the fight for justice is the work of every generation, requiring courage, persistence, and faith that right will ultimately prevail, even when progress seems impossibly slow.

And that, perhaps, is Frederick Douglass’s most enduring lesson: that the struggle for human dignity is never finally won, but must be taken up anew by each generation. Setbacks are inevitable, but surrender is unacceptable. Hope is not a prediction, but a choice we make every day.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load