They say Charleston breathes in whispers—the kind that curl under doors and settle into floorboards the way summer heat does, heavy and inescapable. To read the record as it survives—in faded journals, courtly letters, municipal files, and the private papers that slipped their way into public—there was a season when those whispers turned to smoke. The summer of 1848 was when certain grand houses along the Battery and Meeting Street learned that foundations laid on suffering do not promise sleep. You can call this a reconstruction, a story braided from fragments, because that’s what it is. Not a verdict. Not a newly unearthed confession. Just the heat that still radiates off the documents nobody managed to bury.

It began where all strong Charleston stories begin—in the mansions. The Rutled estate on Meeting Street had stood nearly forty years by then, a three-story federal monument to architecture that hoped to look like order. The family left the city three days before the first fire, decamping for Flat Rock, North Carolina, as elites did in the fever months. Only the servants remained: five enslaved workers tasked with keeping the place breathing while the owners enjoyed mountain air and the memory of power. Around midnight, July 12, 1848, the night watchman saw an orange glow unfurl from the rear of the property. Bells rang. Water brigades formed. But by the time men arrived with buckets and rope and a conviction that habit alone could beat flame, the house’s heart had already been compromised.

What bothered men like Captain William Johnson—a meticulous officer of the City Guard whose notes still sit in the Charleston County Historical Society—wasn’t just the speed of the fire, but its restraint. Only the main house. Not the carriage house. Not the separate kitchen building. Not even the slave quarters a little ways off. A fire that behaved like an argument more than chaos, choosing what to destroy and what to leave standing. The Charleston Mercury’s editor, Robert Barnwell Rhett, would later write in a private letter that survived by accident—family papers never quite get the funeral they want—that the blaze looked “as if someone who had spent years within its walls selected exactly where and how to bring it down most efficiently.” It’s hard to argue with a man who knew the city’s families as if gossip were census.

The household staff gave identical statements: asleep in their quarters, roused by heat and confusion, saw nothing, heard nothing. Johnson thought the uniformity troubling. Either the truth in chorus or something rehearsed, a script for those who knew too much about what happened behind white doors and too little about what would happen to them if they told it.

On July 26, the Pinkney residence on South Battery burned. Same pattern—family away, servants on property, main house only. By August 9, when the Middleton mansion turned to a column of cinders and daylight, the city’s confidence cracked. Nobody wanted to say it out loud, but they did anyway: someone was choosing these homes. Someone who knew the slopes of those staircases and where the walls hollowed. Someone who understood that the largest houses could be undone without touching what lay around them.

The City Council met under trembling chandeliers. The mayor spoke of doubling night patrols, which is what city governments do when buildings burn and they don’t want to ask what else is on fire. Then came the registry proposal—mandatory recording of movements and relationships for household servants. The word “servants,” as always, was a veil that drooped neatly over “slaves.” Councilman James Harrison put the fear raw on the table: The threat comes from within. The room hummed with the framed portrait certainty of men who’d been told their order was the natural one. Quietly, they began to look at the people who poured their coffee and put their children to bed as if the silverware had learned to plan.

What we know next comes from a letter that arrived at the office of the Charleston Mercury on August 21, signed “Justice.” The handwriting belonged to an educated hand—elegant strokes, disciplined spacing. It read: I have burned three houses. I will burn seven more. Authorities sealed the letter from public view, perhaps out of fear of panic or imitation. Maybe out of shame. Another letter would appear later in family archives: Each house represents a sin. Each family carries guilt unknown to the world but known to me. It sounds theatrical when pulled from the file and placed in today’s light, but fire is theatrical by nature. Nobody writes with that tilt unless the words intend to leave a mark.

Johnson’s detectives did what they knew: they made lists. Literate free Black men and enslaved people with access to elite households. Forty-seven names. Interrogations. Handwriting comparisons. Alibis measured against the language of flame. Meanwhile, the city’s finest receded from their drawing rooms as if the walls had turned porous. Those still in town fled. Those already at summer homes extended their reprieve. Houses stood like masks without faces to anchor them.

Then came letters to specific men in specific country houses, letters that didn’t bother with the performance of noble threat. One reached Thomas Grimball near Edisto Island; it named what happened in a cellar in 1843 and said the girl was thirteen. Some documents claim Grimball burned the letter and wrote to Captain Johnson with vague concerns about the pattern of fires. Precise or not, the Grimball house burned seventeen days later. The deviation in this case felt like an admission. The fire started in the cellar, in a room once used to isolate enslaved people deemed “difficult,” later refashioned into storage, as if fresh paint could persuade air it had never carried certain cries.

After that, letters arrived like the quiet ring of a glass on a polished table—present, contained, impossible to ignore. Manigault. Drayton. Ravenel. Old names in any Charleston story that wants to end up in the museum. Each letter carried details like splinters that won’t work themselves out: a young woman sold away from her children after resisting a master’s advances; twins separated despite a promise, which is to say a lie; a cook blinded in one eye after a dish displeased a guest. Dates. Names. Rooms. Times of night. All leading to the same final sentence: The fire comes next.

You can see how a city built on order would prefer a different explanation. Unionists. Northern saboteurs. Criminal men with no cause but chaos. But the letters had the smell of proximity—the knowledge of which stair creaked, which back door latch didn’t catch properly, and what time a study went dark. And the letters kept arriving no matter how closely the post was watched, which suggests what enslaved Charlestonians could have told anyone willing to listen: surveillance doesn’t solve a problem when the problem is the household’s dependence on the very people it refuses to see.

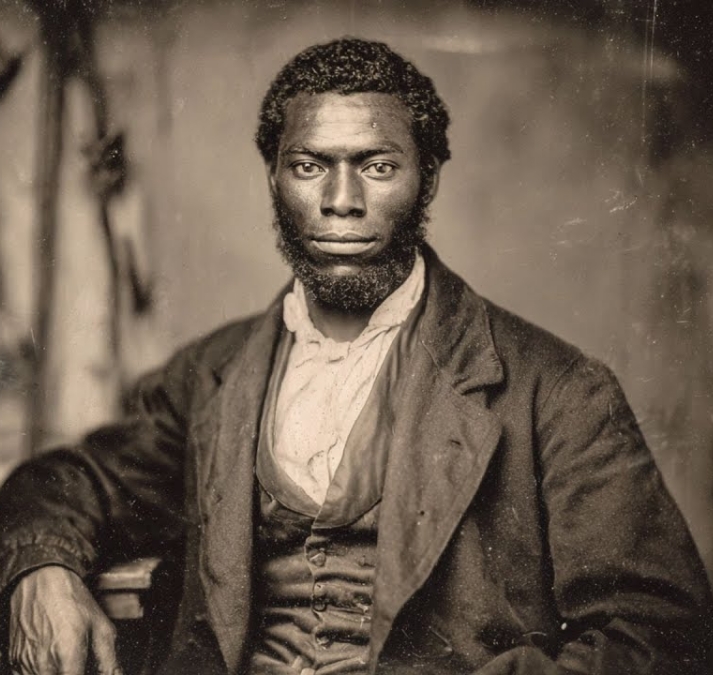

By October, ten mansions were gone, and the fires had leapt from the peninsula to certain plantations in the orbit. It was then, through a captured letter in delivery, that a name surfaced: Joseph Williams. A free Black carpenter—born enslaved in 1810, freed in 1832 by a minister who thought freedom a sacrament one could choose to confer and a skill a holy language—Joseph was known for fine work. He’d been hired to repair and improve the very homes that would later burn. He knew their innards, their temperaments. More than one piece of paper says his mother had been brought to Charleston aboard an illegal slaving ship in 1829, purchased by the Rutleds, and dead by 1833 after the birth of a second child who did not live either. In Williams’s telling—if you lay all the depositions and notes together like planks to bridge a small creek—his mother’s death came not by fate but through neglect, a word that in this context contains as much deliberate choice as apathy.

When the City Guard finally moved on Williams’s small house on Anson Street, he was already gone. Neighbors said he’d left that morning with a small bag for a job outside the city. Inside the house, a locked drawer yielded letters addressed to seven families who had not yet burned, detailing crimes from boardrooms to bedrooms, from auctions to attics. Alongside them lay a journal in his hand. In that journal, he wrote about floor plans and structural vulnerabilities, about the honest carpentry of understanding how a thing stands so you can judge how a thing falls. He wrote, too, that he had not acted alone. That in each house there was at least one enslaved person who had suffered in ways a polite man would not say out loud but which he knew intimately because lives like theirs taught him the cost of knowledge. These insiders provided a kind of access the city forgot it had given.

The last entry of that journal, dated October 29, has been copied so many times by historians and archivists that the words almost seem to belong to the city itself: Ten flames for ten crimes. Justice has been partially served. I leave the remaining seven to God’s judgment as my time here draws to a close. Passage has been secured on a vessel bound for Haiti. By the time this is read, I will be beyond Charleston’s law, though not beyond my conscience. You can hear a certain dignity coiled in that paragraph; also the fatigue of a man who knows the law never had a hand to extend to him in the first place.

The manhunt spread from Charleston outward like circles in a basin. Ships were searched. Descriptions circulated. Alerts sent to Haiti, Jamaica, islands where a free Black craftsman might find a life stitching wood to wind. If you want the neat version, this is where you say he disappeared. If you want the honest one, it’s that the record loses him here and does not pick him up again. No confirmed landing. No burial. Just a vacancy shaped like a person, and in that negative space—speculation. Some swear he made it to Haiti and chose a name that fit in the mouth of a man who wanted to work without being hunted. Some say Canada, some say England where abolition had come earlier and carpenters are always in demand. Others insist he never left, that Charleston does with bodies what it tries to do with history when it’s inconvenient—makes them hard to find.

Captain Johnson retired in 1850 and opened a detective agency. When he died in 1872, his sealed conclusions complicated the story he’d helped write. He believed the evidence against Williams was strong but noticed subtleties: handwriting in the threatening letters that wasn’t quite the same as the journal, details about illegal slave trading too precise to come easily to a craftsman, however brilliant, without help from someone who swam regularly in that money. He suspected a collaborator with access to records only certain white men would see, maybe a conscience awakened, maybe a competitor with motives unclean in their furies. Later, a historian named Margaret Thornwell would publish a study arguing that correspondence among clergymen referenced just such a man, a figure who had participated in illegal slaving and then brought documents to Williams when guilt became heavier than pride. Whether this absolves or incriminates depends on what you think repentance owes the past.

It would be a mistake to make the whole story hinge on Williams, even if the frame he provides is a strong one. The historian’s hand meets the city’s granite here. In 1869, a former enslaved woman named Martha Goodwin gave testimony to a federal commission about crimes committed under slavery. She had served the Pinkneys, the second house to burn. She said the fires were no mystery to those who lived inside those walls. They knew which floorboards creaked and which locks didn’t catch. They knew where the masters were weak. She suggested—and it has the ring of how humans actually manage the impossible—that there was a network. Not a large organization with titles and minutes, but something more native to survival: an invisible community of the people who remember and share because sharing is the only insurance policy available to them. When the letters arrived, word spread through laundries and kitchens and stable aisles, through stairwells and water yards. Many knew Joseph Williams. Some helped him. None betrayed him.

In 1952, a ledger appeared during renovations of a carriage house that belonged to a family the newspapers used to butter when they wanted a public favor. The ledger, water-damaged but legible enough, listed dates, names, deliveries, windows of time when certain properties lay most open to entry. A historian studied it; then it vanished from the museum that was meant to protect it. Official explanations shuffled. The absence said more than a paper ever could.

There were other documents, too, that made the story ring with tonal complexity rather than rage alone. A Union Army chaplain recorded the deathbed confession of a plantation overseer named Samuel Porter in 1865. Porter claimed that Williams had first pursued legal remedies, bringing evidence of illegal slave trading to white abolitionists, hoping that the system their sermons described would produce justice. He was told—reliably and repeatedly—that courts in South Carolina would not hear a case against the city’s fathers. Porter said that after these failures, Williams decided that if the law offered no justice, justice would go to work without the law. The confession also offered a name, a lawyer educated in the North—Harold Whitmore—who may have supplied the documentation about the consortium financing the illegal trade. Records show Whitmore left Charleston abruptly in October 1848 and resurfaced in Boston. Gaps in his journals sit where the years 1845 to 1850 should be. Absence again, doing its sly work.

There is something like a soft thud that comes after heroic architecture fails to hold. In November 1848, the city’s newspapers—after weeks of loud coverage—grew quiet. An editorial counseled silence in the name of civic calm. Arrests were made: twenty-seven enslaved or free Black people suspected of involvement. Three died in custody, which is a sentence that leaves too much undescribed. Others were imprisoned or sold south. Johnson himself admitted in a private letter that politics had overwhelmed justice, that he was being directed to look only toward the Black carpenter and away from any avenue that might adjust white reputations in the ledger of blame.

If you live in Charleston long enough, you learn to read negative space. Empty lots in a row of period houses tell their own kind of truth. So do certain absences in historical societies where documents surely once lived. In 1965, a historian named Gerald Haywood found records at the Charleston Orphan House of four children surrendered by Joseph Williams in October 1848, their mother Sarah gone two years by then. The letter that accompanied their admission did not read like a father abandoning, but like a man calculating the cost of his path. He wrote that the path could not accommodate innocence and asked that his children be spared the burden of his actions and the retribution to follow. He left funds for a year of care and asked that they be placed with god-fearing families beyond Charleston’s reach. If you want to draw his portrait from these lines, you’ll need to accept that men can be both relentless and tender, both relentless because they are tender.

Every city has its rituals for memory, and every city has its counter-rituals for forgetting. In 1910, a committee took it upon itself to harmonize Charleston’s history, which is to say sand down what made the furniture wobble. The mansion fires, with their implication that the most generous men in the city had committed crimes even federal law frowned upon, did not harmonize easily. So the committee did what committees do—it fragmented. Each fire a separate story, each set of ashes a personal misfortune, each letter a curiosity unrelated to the next. A century later, tour guides still point to carved crests and cupolas and gossip that skims the surface like a dragonfly. Very few will say Joseph Williams’s name out loud. Fewer still will tell you what Martha Goodwin testified, or how an old carriage house ledger briefly surfaced like driftwood only to disappear downstream.

Some artifacts burrow through the walls anyway. In 1965, a sealed box turned up inside the fire department headquarters during renovation. Inside, a single sentence in that same elegant hand: Justice comes for everyone. If not in this life, then in history’s judgment. People argue over its provenance. Some insist it’s a later forgery. Others say it confirms a throughline—someone who wrote well, who planned carefully, who left messages that were as much for posterity as for panic.

There’s a temptation to call this a revenge story. That would let it slide nicely into a shelf with familiar spines. But revenge is often indiscriminate. What happened in Charleston in 1848 was precise. Ten houses burned. Ten families whose names show up in research on illegal slave trading. The fires never became a wholesale war against houses with rich white people living inside. Not a public uprising in torches and shouts. More like surgery. More like an audit. Which is perhaps why the city tried to convert it into noise. Citizens can sleep through noise. They cannot sleep through an accounting.

I’ve been told that on certain summer nights near the Battery, people still think they catch smoke on a wind too still to move leaves. It’s probably the old factories, or just the city being dramatic as it likes to be when the heat feels like a hand. Still, if you stand near where those houses once drew their shade and listen past cell phone cameras and carriage wheels, you can almost hear the clatter of a hammer in a carpenter’s hand and imagine how such a hand learns to count, to plan, to measure—how it learns that what you build is not always a house.

The epilogue the city prefers is probably the Middleton note, found in a cavity behind a mantelpiece during a renovation in 1970, written in the same beautiful script that tried to educate a city in the language of consequence: Remember that foundations built on suffering will never stand secure. The past is never truly buried. Justice may delay, but it does not forget. The family donated the note anonymously to the museum, where it had a brief moment in glass before vanishing back to storage. The display label was short, the way labels are, and didn’t mention how hands tremble sometimes when they recognize their own history looking back at them in lines.

If you need resolution the way a playbill promises intermission will end, this is not that kind of story. The fires cooled. The families, some of them, rebuilt or moved or shrank their names to fit new times. The war came and remade the map. Emancipation cracked the legal bones of a system while its marrow remained stubborn in places. The conspiracies and counter-conspiracies still spark debates among historians over beer and footnotes, and nobody gets the last word because the archive refuses to yield it. What remains is the shape of the narrative drawn by what’s missing as much as what’s present: a man of skill and grief; a network of people who were asked to be invisible and decided visibility could take a different form; certain white men who slid documents across a table either because their conscience woke or because vengeance fit their ledger; a city that chose silence because the alternative threatened to make a mirror of its museums.

There is one more fragment, offered almost as a grace note. Frederick Douglass wrote, in 1871, about an elderly carpenter he met in Haiti whose knowledge of Charleston’s society was such that it felt lived rather than learned. He didn’t give the man’s name because why would he? It was a meeting in the passage of life, and Douglass did not yet know the uses we would try to make of such encounters. Believe that story if it helps you sleep, or if it helps you hope. Disbelieve it if your trust does not travel easily to rumor. Either way, the fires did their work. They turned secrets into air, and air into memory, and memory into a warning: that the same hands which lay cornices and raise beams can also find the single point where a structure surrenders.

What happened in 1848 was not a myth conjured to satisfy a modern appetite for retribution tales. Ten houses burned. Captain Johnson’s notes exist. Martha Goodwin’s testimony exists. Certain letters survive. A ledger surfaced and then did not. An orphanage log bore the names of four children who are not characters but lives. The explanation is not singular. It is woven, as the best and worst of our histories are, out of complicity and courage, indifference and calculation, rage and restraint, sorrow and skill. That’s why it stays with the city and with anyone who reads the archive long enough to feel the edges of pages that heat once touched.

If you come to Charleston, remember that stories persist along the seams. You’ll see restored facades and palm trees trimming long avenues of old money. The tour will be handsome and pleasant and not wrong—just incomplete. Walk a side street. Look for a gap where a grand house might have stood. If you stand there long enough, you’ll feel the smallest shift in the air. The city is telling you, as gently as it can, that some foundations endure and some give way—and that sometimes the difference is whether the people you ask to carry your life inside their hands decide you deserve to keep it.

The last word belongs, perhaps, to the carpenter’s journal, whether it was his hand that wrote every line or a community’s voice that steadied it: They believed their wealth made them untouchable, their position unassailable. They forgot that the same hands that built their mansions could also reduce them to ash. History will remember that no one stands above justice forever. You can argue who wrote it, and you can debate what justice meant, and you can point to all the places where the evidence thins like paper in flame. But what you cannot do—not honestly—is pretend the smoke never hung over the Battery, or that in those weeks of 1848, Charleston didn’t learn that the people it refused to see could seize the night and make it say what the day refused to pronounce.

As for how a story like this should be told now—carefully, with sources noted in spirit if not in footnotes; with respect for the living descendants on all sides; with the humility to say “likely” where certainty will not consent; with a refusal to dress speculation as fact and an equal refusal to let silence rewrite consequences. That’s the point, really. Not to sensationalize, not to fling gasoline across memory, but to hold the narrative at an even heat until the shape of it emerges. If readers walk away recognizing the difference between what is documented and what is inferred, if they feel the craft, if they are moved rather than manipulated, then the story has done the one thing an honest story should: it has made the truth more legible without pretending it’s complete.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load