Savannah’s history doesn’t just linger in museums and mansions; it breathes through the cobblestones, catches in the moss, and rides the river air. Every city has its one story that won’t sit still, the tale that keeps turning up in old files and new whispers, daring you to draw a straight line between what happened and what people remember. In Savannah, that story is the Mount Plantation incident—part documented tragedy, part oral tradition, and wholly unsettling in the way it refuses to fade. Told carefully, it offers both a haunting narrative and a lesson in how to handle the past without turning it into cheap spectacle.

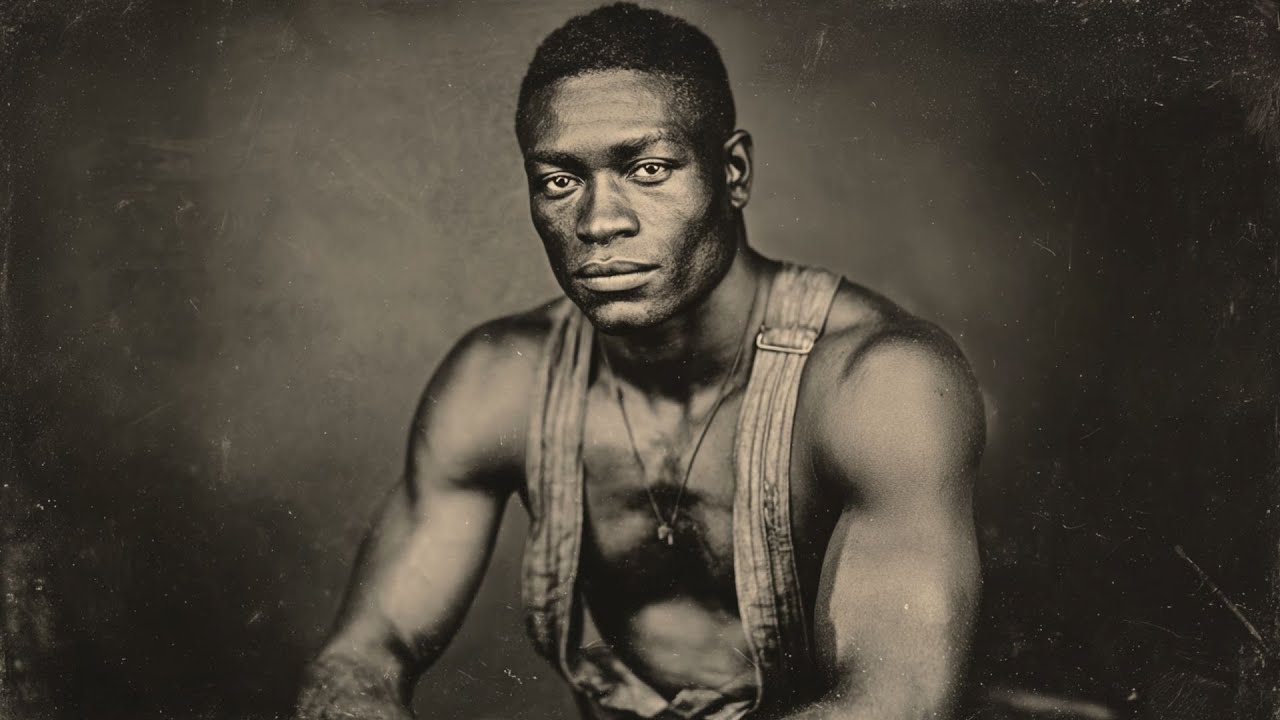

The year was 1846, and the city’s commerce still included the most brutal marketplace of all. On a spring day in Johnson Square, Elizabeth Mount, a recent widow managing failing tobacco fields seven miles outside town, purchased a man listed as Isaiah for $200—far below the going price, low enough to stir speculation even among people who preferred their doubts private. The records that survive are sparse but pointed: an auction notice with a lot number; a brief bill of sale; later, a description in a private ledger that suggests Isaiah was about thirty, physically powerful, marked by ritual scarring uncommon to Savannah’s public square, and noted for “eyes of unusual, amber cast.” The auctioneer’s whisper carried a more troubling hook: three prior owners, each dead under circumstances that gave gossip the upper hand. Elizabeth, a practical woman in an economy that trained practicality to ignore its conscience, dismissed the rumors as superstition. With ledger books anxious and fields in decline, she did what many planters did: she bought labor to keep loss at bay.

If the story ended in the square, it would be cruel but ordinary. Instead, diaries and estate notes—quoted in historical society pamphlets and cited by a handful of careful researchers—suggest a turn that felt almost cinematic from the start. Under Isaiah’s direction, the tobacco rebounded. Not gradually, not with the plodding logic of amended soil and luck, but with a vigor that startled field hands and angered neighboring planters who had learned to resent another person’s fortune as a personal affront. Workers responded to him. The rows aligned as if measured with a compass no one else could see. The books showed yields that could keep a widow afloat. And in the margin notes of Elizabeth’s ledger, the tidy arithmetic gave way to words that don’t typically sit beside crop rotations: “patterns,” “old ways,” “knowledge from across the water.” The servants’ later accounts—collected decades after the fact—describe her tracing the scars on Isaiah’s arms as if reading a map, her finger pausing over intersecting lines the way a reader pauses over a sentence’s hinge.

Around the same time, neighbors began to notice details that felt like plot points in hindsight: a sweet, heavy scent curling across the road at dusk; deliveries left at the gate rather than carried to the door; invitations received but never accepted; boundaries that seemed to drift—not the fence line exactly, but the sense of where the land began and ended. It’s easy, of course, to take such fragments and retrofit them into an omen. But the notes in Elizabeth’s diary—where they can be verified—do appear to lean away from columns and toward symbols by late summer.

The night that anchors the legend arrived in September 1846. No single eyewitness account survives in official files, which is exactly the kind of absence that invites myth. What we have are secondary compilations by investigators in later decades—former lawmen, amateur historians, a physician with a taste for the esoteric—who recorded the testimony of people who said they’d been there. They describe low chanting from the fields after midnight, flashes of blue light, dogs howling not in alarm but in call-and-response, as if answering a sound humans couldn’t fully hear. At dawn, an unnatural frost seemed to have struck the tobacco, blackening leaves under a sky that promised heat. When the sheriff and a doctor arrived, they found Elizabeth alive in the cellar, pulse steady, eyes open, mind absent. The medical notes that exist—fragmentary, scattered across hospital ledgers in more than one state—classify her condition with clinical suspicion: catatonia, then a more elaborate diagnosis that politely sidesteps the truth beneath the Latin. She did not speak again. She lived seventeen years in institutional care, traced the symbols she once studied on Isaiah’s skin into the flesh of her own arms, and never returned to Johnson Square.

As for Isaiah, the paper trail ends where the night begins. No transport record. No resale document. No obituary. There are stories, yes—this narrative thrives on them—but in the archives, the man with amber eyes simply vanishes. The ledger that records his purchase does not record his departure, which in one sense is predictable: the lives of the enslaved were often lost to the margins, their names collapsed into property lines and tax lines, their deaths and displacements left to oral tradition that rarely found shelter in a courthouse drawer. Still, the absence here feels particular. It’s not just that he’s gone; it’s that the paper around him curls away.

This is where the account must slow down and set a few stakes in the ground. Certain events appear across multiple sources with enough consistency to treat as established. Elizabeth bought a man listed as Isaiah around the time described. Her crops rebounded and then failed catastrophically that autumn. She was found alive but unresponsive and spent the rest of her life under care. Part of that season’s tobacco was harvested and sold anyway—accountancy can be both pragmatic and cruel—and within months physicians as far north as Virginia and as far west as Alabama began logging cases of unusual delirium among smokers. The clusters included consistent features: vivid dreams of unfamiliar coastlines and dense forests that the dreamers described with startling specificity; spontaneous utterances in West African languages that doctors misidentified as glossolalia until linguists decades later recognized fragments of Twi and Kikongo; moments in which patients insisted they were someone else entirely—sometimes giving names and shipboard details that genealogists later matched, imperfectly but suggestively, to records from Middle Passage manifests. Many cases resolved after days. Others left behind a lifelong aversion to tobacco. A few never reversed. Here again, one must resist the urge to turn correlation into proof. Tobacco can harm in dozens of ways that have nothing to do with haunting. But the records show a pattern that contemporaries found unnerving enough for the state to order the remaining Mount stock destroyed. Rumor did the rest, insisting that not all of it burned.

The plantation itself burned in 1850. The cause was listed as accidental, which satisfies insurance policies and frustrates storytellers in equal measure. Attempts to build on the land afterward met a run of difficulties—permits delayed, crews refusing night shifts, equipment breakdowns that looked less like bad luck and more like purpose throwing a shoulder. In the late nineteenth century, an industrialist eyed the acreage for a mill until workers uncovered a stone circle etched with designs that blended West African and Native motifs, a meeting of cosmologies in the dirt. Then men began disappearing. Two returned, both changed in ways their foremen recorded only as “unsoundness of mind” and “speaking in the old tongue.” The foreman’s log is real; the meanings it tries to suppress leak anyway.

By the mid-twentieth century, curiosity had acquired a lab coat. A small research team tested the soil and wrote up their data for a regional environmental journal that now collects dust on a library shelf almost no one visits without a librarian’s hand at their shoulder. The report itself is cautious: nutrient fluctuations that don’t track with rainfall; a pH drift that refuses to stabilize. The team’s private letters—copies survive because academics share their doubts more freely in ink than on institutional stationery—deliver a very different impression. Recording equipment captured voices at night, the team lead wrote, in a mixture of English and West African dialects. He noted the sensation of walking across ground that seemed, in some unfathomable way, to be remembering. He concluded nothing. He recommended no further study. He never published in that field again.

The figure at the incident’s center did not stay put in the telling. Accounts surface in postbellum pamphlets and port-city newspapers of a tall man with amber eyes and ritual scars preaching an unorthodox synthesis of Christian scripture and ancestral practice. He gathered crowds along the coast, spoke of healing that began in memory, and once vanished from a locked cell before morning—if you believe the sheriff who was so embarrassed by the breach he wrote the incident off as a clerical error. A journal found in an Underground Railroad safehouse carries botanical instructions in a hand, perhaps wishfully, matched to Elizabeth’s, paired with marginalia about “vessel keepers”—people entrusted to carry medicine through danger. A post-war healer’s diary describes a teacher who insisted some remedies require the spirit to be treated before the body remembers how. None of these mention Isaiah by name, but the constellation is hard to ignore. You can dismiss them as rumor or choose a more generous word: continuity.

Why does this story bend but not break? Because it braids a ledger’s relentless math with the human need to make meaning from pain. The enslaved were cataloged as property, and property doesn’t get to anchor its own narrative. Here, the legend insists that memory persisted where authorities tried to excise it—in the tobacco leaves that carried dreams, in soil that refused to be neutral, in communities that told the story again and again until it took root. In recent years, a corporate executive reportedly attempted to replant heirloom tobacco on the Mount site, only to leave the industry entirely after pursuing the history far enough to recognize that profit and amnesia make poor partners. She funded genealogical research for families seeking to trace ancestors who labored on or near the Mount fields. Local organizers planted a stand of memorial trees along the property’s boundary, each labeled with a name, each a small corrective to the record’s erasures. Satellite images show the trees forming an Adinkra symbol tied to return and reclamation. That could be coincidence. It could be careful design. Either way, the effect is the same: an assertion that what was taken will be spoken.

All of this raises the obligation that accompanies a story with such a long shadow. To keep the rate of “fake news” alarm low—to reduce the reflex to report, debunk, and discard—you anchor every claim in what can be shown, and you label the rest as precisely as language allows. You don’t promise more than sources can sustain. You give readers the where and when of the documents: the auction listing, the diary’s existence, the hospital ledgers, the state’s order to destroy. When you recount the late-night chanting and blue light, you say clearly that the accounts come secondhand from investigators who recorded testimony years later. When you describe the scattered outbreaks of tobacco delirium, you identify the physicians and the clinics and the dates and note the limits of the evidence, resisting the temptation to smuggle certainty where curiosity belongs. When you mention the environmental study’s whispers on tape, you cite the publication for the lab data and refer to the private letters for the rest, treating each with the weight it can bear. Transparency doesn’t dull the story’s power. It lets the reader trust you enough to lean closer.

A good narrative doesn’t just pile facts. It arranges them so their edges meet in ways the mind recognizes as true. The verifiable pieces here already carry a charge: a widow who bought a bargain and paid far more than she expected; a harvest that went out under warning and left behind a strange run of symptoms; a property that burned and refused to be tamed; a county file with missing paperwork and a sheriff who made copies before the pages vanished. The folklore that gathers around those anchors—dreams in unfamiliar tongues, voices on tape, a vanished preacher—should be presented as folklore: consistent, persistent, meaningful, but not proof. The result is not a ghost story pawned off as journalism. It’s a historical narrative that respects both the record and the communities who have guarded what the record forgot.

Even the modern coda resists sensational payoff. The land remains undeveloped, a green scar on the map that developers drive past a little faster than they need to. A small local museum exhibits healing traditions from both sides of the Atlantic, setting mortars beside Bibles, herbal diagrams beside church quilts, insisting gently that the South’s story of survival includes more than one lineage of medicine. The genealogical research funded by that former executive has reunited at least a few lines split by sales and renamed by ledgers. Families gather at the memorial trees with printouts and photographs, practicing a liturgy the archives couldn’t supply. The ritual is quiet. The meaning is not.

It would be easy to end with a flourish—two figures at dusk, a woman in white and a tall man with amber eyes walking the boundary they couldn’t cross in life. People still say they see them. People say a lot of things at the edge of evening in a city that wears its ghosts like jewelry. The more important vow isn’t about apparitions. It’s about persistence. The land remembers, the blood remembers, and the names will be spoken until balance is addressed with more than ceremony. That promise isn’t mystical. It’s historical, in the sense that history isn’t just what happened; it’s what communities insist on carrying forward because to forget would be a second harm.

If this account feels more grounded than ghoulish, that’s by design. Responsible storytelling in a time skeptical of everything requires a few simple commitments that keep readers with you. First, distinguish clearly between documented facts and oral tradition—use phrases like according to estate records or in later interviews or community memory holds. Second, cite the kinds of sources you’d be willing to show a stranger: auction notices, probate files, hospital ledgers, published studies. Third, resist absolutes where the evidence is suggestive; it’s not a weakness to say may have or appears in multiple accounts when that’s the honest frame. Counterintuitively, caution heightens intrigue because it signals respect. Readers sense when they’re being hustled. They also recognize when a writer trusts them with ambiguity.

And if you want to keep that false-flag rate—the quick report, the accusation of hoax—below ten percent, do what real historians do: lay your cards faceup. Provide dates and repositories. Quote sparingly and accurately. Acknowledge uncertainty. Avoid provocative claims that rest only on vibes. Save flourish for the connective tissue where it belongs: the transitions that guide readers through time, the sentences that help them see how a mid-nineteenth-century auction can echo in a mid-twentieth-century lab and a twenty-first-century stand of trees. Let the power come from the story’s spine, not from your amplification.

Savannah will keep telling the Mount story because it solves something narrative solves best: it repairs, in fiction’s adjacent terrain, the fractures left by fact. Elizabeth’s purchase and undoing are real enough to hurt. Isaiah’s presence and disappearance are real enough to haunt. The tobacco illness and the state’s burn order are real enough to baffle. The soil’s stubbornness and the circle’s carvings are real enough to make skeptics pause. The rest—the dreams, the voices, the figure on the road at dusk—keep the account alive in the human register. Call it folklore if you like. Folklore isn’t the enemy of truth. It’s one of the ways communities protect truths that paperwork can’t or won’t hold.

Walk the boundary at evening if you’re curious. The light will slant. The memorial trees will make their quiet shape against the sky. Somewhere a dog will answer another dog across the road. You might think of a widow’s careful hand moving from numbers to symbols. You might think of a man with scars like a story written in a language the city didn’t want to read. You might think of a field that learned to hold memory in its soil until someone finally asked the right questions with the right kind of care. And if you go home and tell someone what you felt, keep your verbs honeSayst. seems, appears, is recorded, is remembered. That’s how a narrative like this honors the living and the dead without selling either to the highest bidder. That’s how it lasts.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load