There’s a place on Galveston Island where the breeze off the Gulf feels colder than it should, a thin seam of air that seems to remember what the soil refuses to give back. People drive past it every day—on their way to work, to dinner, to beat the evening rush—and never suspect that beneath the asphalt, history once tried very hard to disappear itself. The site doesn’t bear a famous name, no bronze plaque with heroic inscriptions. It’s just a parking lot, quiet and ordinary. But the story tied to that ground is anything but, and the fragments we do have are enough to draw a rough outline around something deeply human, deeply cruel, and disturbingly plausible.

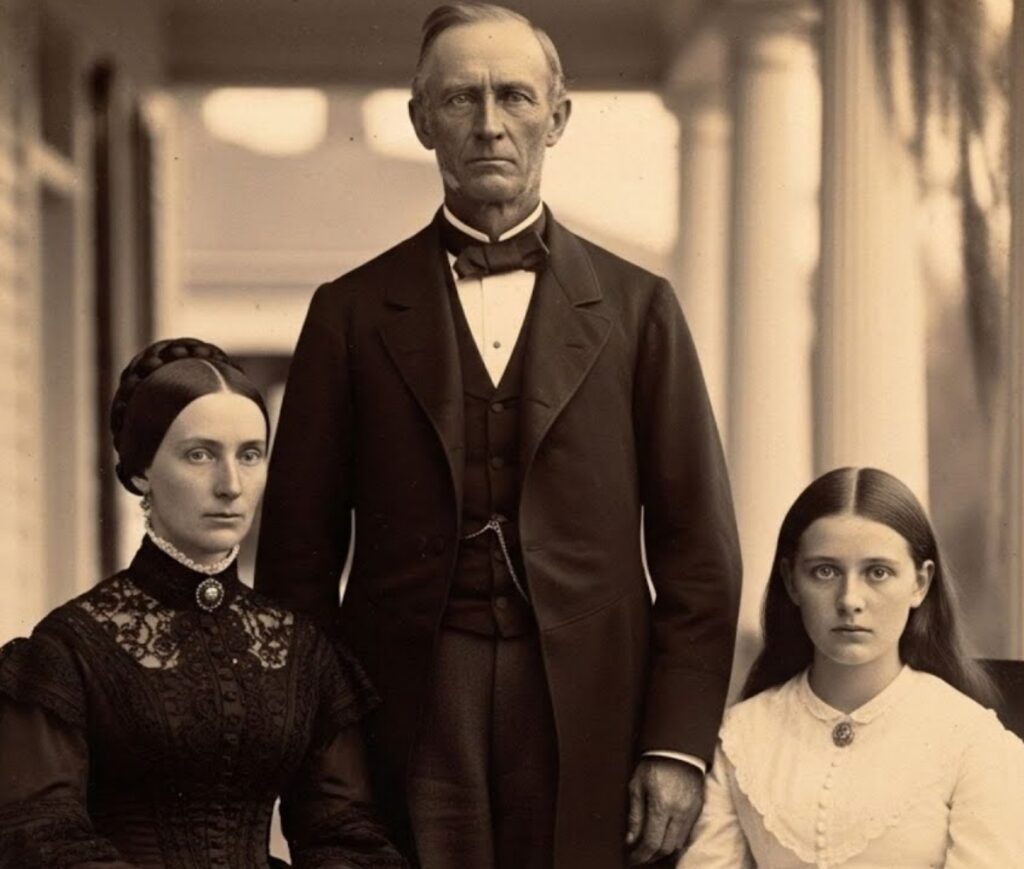

In the summer of 1856, while Galveston celebrated its rising fortunes as a booming port, the Cole plantation sat three miles east, a spread of cotton and hierarchy, its main house lifted on pillars above the flood-prone flats. From the harbor you could see the white columns watching the prairie, the house as crisp as a letter of introduction. Nathan Cole had found his place as a wealthy planter; his wife, Rosalie Duval, ran the household with a blend of decorum and distance that earned her praise in polite company. And yet, within those walls, something shifted. It didn’t announce itself. It accumulated—like heat, like a whisper, like a ledger page torn out and never seen again.

The records that survive establish a simple, unsettling difference: in January 1856, the plantation reported forty‑three enslaved people. By December, twenty‑nine. Fourteen names vanished from the books without death notices or sales. There’s nothing on paper to say where they went. County archives that might have helped answer the question contain gaps; the plantation’s own ledger appears to have lost several pages with a careful hand, not an accident. It would all have remained a rumor with a footnote if not for what a crew found in 1964 under the dining room floor—a sealed space, a tin box, a leather‑bound journal.

The handwriting belonged to eighteen‑year‑old Elizabeth Cole, Nathan and Rosalie’s daughter. Her entries traced six months in 1856: the quiet tightening of rules; doors that clicked locked at sunset; meals eaten in silence as her father lingered in his study; her mother’s sudden devotion to confession at St. Mary’s. Elizabeth recorded details that feel small until they collect together—soil tracked in near the study, padlocks newly installed, old staff dismissed without word. A house servant named Sarah trembled with a cloth bundle to her chest and a warning: some things are better left unseen. Two days later, Sarah was gone.

From there, the nights grew longer. Elizabeth heard scraping under the floorboards, metal biting earth, a smell that wasn’t just damp dirt but something sour and metallic slipping between the boards. When she pried up a floor in the pantry and slipped a lantern into the cool shade, the light caught rows of rectangular impressions in disturbed soil, too small for grown bodies, too regular to be accidental. The next day, the floor she’d lifted was nailed shut and a heavy cabinet was pulled over it. In August, the plantation received twenty barrels of quicklime, handled personally by Nathan, with the tidy explanation of garden soil treatment for a place that had never tended a garden on the north side.

By then, church registries showed Rosalie’s attendance soaring. Father Thomas, the parish priest, wrote in his private notes about salvation and sacrifice spoken in a way that made doctrine feel bent, the word cleansing recurring like a badly tuned bell. Elizabeth’s entries changed key as summer burned on. She told the pages what she couldn’t tell anyone else: barred windows, locked doors, the doctor summoned to declare her agitated but physically fine, a recommendation to keep her indoors for her own good. She saw collusion everywhere she looked and, at least once, she may have been right about it.

On a September night, she woke to find her mother sitting at the edge of her bed, hands cold, voice soft, promising that a daughter’s curiosity would soon harden into duty. Their position, she said, required contributions. The family legacy demanded it. Soon, she said, it would be Elizabeth’s turn.

The journal’s last dated entry came on October 3. Three lines, brisk as an intake of breath: They are planning something for the new moon. I have found a loose board in the window frame. If I do not have another opportunity to write, know that what happens beneath this house is not the will of God. After that—the paper falls silent.

What followed in the world outside the journal reads like the aftermath of an event that never officially happened. Elizabeth was said to be sent to relatives in New Orleans; no record shows her arrival. No marriage certificate surfaces. No burial. Meanwhile, Nathan sold portions of his holdings despite bad market timing. The couple retreated from society. A letter from a neighbor described Rosalie as gaunt and distracted; whispers said workers refused assignments on the property, that deliveries arrived at odd hours. By the next spring, the sheriff had investigated Nathan for threatening a merchant at gunpoint and found the house boarded, grounds overgrown, explanations thin.

In September 1857, as if the island itself had grown impatient, a hurricane struck hard. The plantation suffered heavy damage. The clean‑up turned something up—human remains on the property. A brief notice in the Galveston Daily News acknowledged the discovery. Follow‑up never came. The sheriff’s report, careful and limited, concluded the remains likely dated to the previous year; identity and cause of death could not be determined. The case closed inside three weeks, then sank. Nathan and Rosalie moved to Houston. He died of liver failure in 1862. She died three months later, reportedly by her own hand. A short obituary mentioned she was preceded by her husband and daughter—the rare, public admission that Elizabeth did not simply vanish into finishing school life.

Most stories end there. But this one kept producing scraps: a ground survey in 1968 found a pattern of soil disturbances six to eight feet down, half an acre’s worth, neatly arrayed. Recommendations for an archaeological study went unheeded; a parking lot went in instead. In 2015, resurfacing revealed unusually high concentrations of calcium compounds—consistent with quicklime—in the soil beneath. Years earlier, workers claimed to have found a brick-walled chamber with iron rings on its walls and channels cut in the floor, then were told to seal it and forget it. Oral histories carried warnings: when the mistress takes to praying and the master takes to drinking, keep your head down and your feet ready.

And there was one more piece. In an estate sale in 1968, a page surfaced among the late Dr. James Hargrave’s notes—a transcription he claimed came from Elizabeth’s journal, dated September 25, 1856. It described following her parents to the cotton barn. Inside, a room refitted like a workshop: tables, implements, chemicals, a ledger, quicklime below the floorboards, the language of inventory and reduction. It described a man—Thomas, long known on the plantation—brought in unconscious. What happened next, the transcription said, her mind could barely bear. The page referenced jars, a document with Chinese characters, contacts in New Orleans, and prices that moved in quiet hands. It said the pits beneath the house served as temporary storage before the final dissolution. It said the missing had not been sold. The word harvest appeared. It said the parents planned to bring their daughter into the enterprise. It ended with a plea to the priest for sanctuary and a blunt prayer that if the page survived her, it would testify.

If that transcription is genuine—and no one has proved it conclusively either way—it offers a horrifyingly mundane explanation that fits too neatly with the gaps: the ledger pages lost, the lime, the subfloor depressions, the jars found in 2005 containing degraded human tissue preserved with period appropriate solutions, later labeled historical medical specimens of unknown origin. It also threads toward New Orleans, where a physician notorious for controversial anatomical research wrote about receiving specialized preparations from a Gulf Coast supplier whose skill surprised him. His surviving notes hinted at tissue studies sorted by race—a pseudoscientific obsession of the era. It is not proof. It is a shadow crossing a field where the rows line up too exactly to be coincidence.

Around the edges of the main story, there are other hints. Financial records show Nathan stretched thin after the banking troubles of 1855, loans pressing, land newly acquired but poorly timed. Rosalie traveled to New Orleans multiple times and came home each trip with gold. A doctor who examined Elizabeth wrote a letter to the sheriff describing locks, barred windows, surgical tools in an unlikeliest setting, a canvas‑wrapped shape carried swiftly out of sight near the barn. He never sent the letter. Years later, his family found it folded into a hidden pocket of a medical bag and donated it to the local historical society. It sits there now, a document that almost mattered.

When you lay the fragments side by side, they don’t resolve into a clear photograph. History rarely grants that luxury, especially when people took pains to blur the negative. But the outline is there, and it looks like this: a family under financial pressure, a household tightening around secrets, a restricted east wing, a pattern of disappearances that remain unexplained, quicklime ordered by the barrel with no credible agricultural purpose, disturbances beneath a raised house in precise rows, a sudden hurricane that muddied and erased, a short official inquiry that concluded nothing at all, and a community that chose not to look too closely at a story that stained every hand it touched.

The horror of it, if you accept the most plausible reading, is not supernatural. It doesn’t need ghosts. It needs only a set of incentives, a lack of oversight, access to human bodies reduced to property, and the ready market of an era when medical schools and private collectors looked the other way if specimens arrived in good condition and asked no questions about provenance. That’s what makes it linger. It feels possible. It feels like the kind of thing people convince themselves they must do when debt closes in and their reputations are their last currency. And once they cross that line, it becomes easier to tell themselves the second time is necessity too.

Elizabeth’s fate is the shard that cuts the deepest. A register from the Louisiana State Insane Asylum in 1857 lists a Miss E.C., nineteen, committed by family for “dangerous delusions,” reporting that her parents were killing people and fearing she would be next. She died six months later, the record says, of brain fever. Is that Elizabeth? The timing is exact. The initials match. The claim lines up precisely with what her own journal described. It remains unproven—but it would be one last, bitter loop in a pattern we’ve already seen: a witness dismissed as unwell, her words filed away in a building that swallowed names.

The decades that followed layered over the story like sediment. Owners came and went, each one encountering some ineffable resistance from the land: buildings that refused to hold, fields that turned uncooperative. A survey flagged the grid under the earth. A resurfacing project measured lime. Work crews found a leather‑bound something under the pavement that crumbled at the touch and tossed it with the fill. A historian tracked a pattern that extended beyond the Cole property—other families, other reductions in enslaved populations during the same years—and lost her funding before she could publish. That alone doesn’t prove a conspiracy. It does suggest an appetite for forgetting.

If you want to tell this story without tipping into the sensational, you do it like this—you say what the records say, you name what they don’t, and you let the reader feel the unease of the space between. You don’t accuse; you present. You don’t embellish gore; you acknowledge the human stakes with restraint. You use the language of possibility where proof is missing and the language of certainty where documents exist. You remind the audience that the most chilling thing here is not a ghost but a ledger and the ease with which people become numbers that can be erased.

Because there’s another truth tucked into this one: the South of the 1850s was an economy built to convert lives into labor and labor into wealth, with the paperwork to prove it. In that world, it would not require a leap—from a certain kind of mind under a certain kind of pressure—to imagine a way to reduce costs and sell what could be sold, to treat human bodies as inventory even after death when, strictly speaking, the market said they were never alive as persons to begin with. That’s the part that settles under your skin. The horror is not exotic. It’s transactional.

So picture the Cole house one last time, the white columns against a flat sky, the stair treads worn smooth by years of careful footsteps. Picture Elizabeth on the landing with a lamp cupped in her hands, listening to the scrape below her, the metal on stone, the murmur that never rises above a whisper. Picture Sarah, clutching a bundle in the kitchen, and the way fear drains someone’s face of everything but resolve. Picture a page in a journal, a quick hand, a final entry the size of a prayer: not the will of God.

And then picture the parking lot. It’s morning; deliveries pull up; car doors thud; someone checks a phone; the air tastes of salt. You wouldn’t know. You couldn’t, unless someone told you. But stories have a way of surviving, even when the people with power try to starve them of oxygen. They slip into letters hidden in medical bags, into surveys filed in cabinets, into the notes of a priest who sensed a doctrine twisted out of shape. They rest in the oral histories of those who kept each other alive by saying the quiet warnings out loud. They wait in the blank spaces where fourteen names should be.

If justice is not possible, acknowledgment is. It’s small, but it shifts the ground a little. It says the missing were real, that their lives mattered, that the silence around them was not an accident. It resists the tidy urge to pretend that the worst we’ve done is the worst we’ve admitted. And it understands that repeating this story responsibly—clearly flagged as a reconstruction from fragmentary sources, careful with claims, serious in tone—does not stoke ghoulish curiosity so much as it counters the one thing that enabled the horror in the first place: the willingness of a community to look away.

There’s a line that runs from that house to the present—through archives, through a hurricane, through a resurfaced lot, through a set of choices that men and women made when their titles and debts mattered more to them than anything else. Following it doesn’t require belief in anything supernatural. It requires the opposite: a belief that people can do terrible things for ordinary reasons and hide them well enough that it takes a century and a half for us to arrange the surviving pieces into an outline that makes us shiver.

If you ever find yourself east of the old port, waiting under the Galveston sun as the asphalt warms under your feet, you might remember this: beneath that quiet surface, the earth keeps its own counsel. It holds patterns, residues, and the pressure of old air. It has no obligation to confess. That part is on us. We are the ones who decide whether to keep driving or to stop and say the names we don’t have, to sit with a story that won’t give us the comfort of certainty and won’t let us escape the weight of what’s likely true. The lesson is not a haunting. It’s a warning. The worst horrors don’t need the dark. They need only a little privacy, a ledger, and a silence that too many people agree to keep.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load