Charleston, South Carolina, 1839. The city moves with the slow, humid pulse of summer, its air heavy with salt and magnolia, its beauty masking a brutality so ordinary that it rarely merits comment. In this world of iron gates and colonnaded mansions, wealth is built on suffering, and the line between refinement and violence is drawn as sharply as the shadow beneath a garden wall.

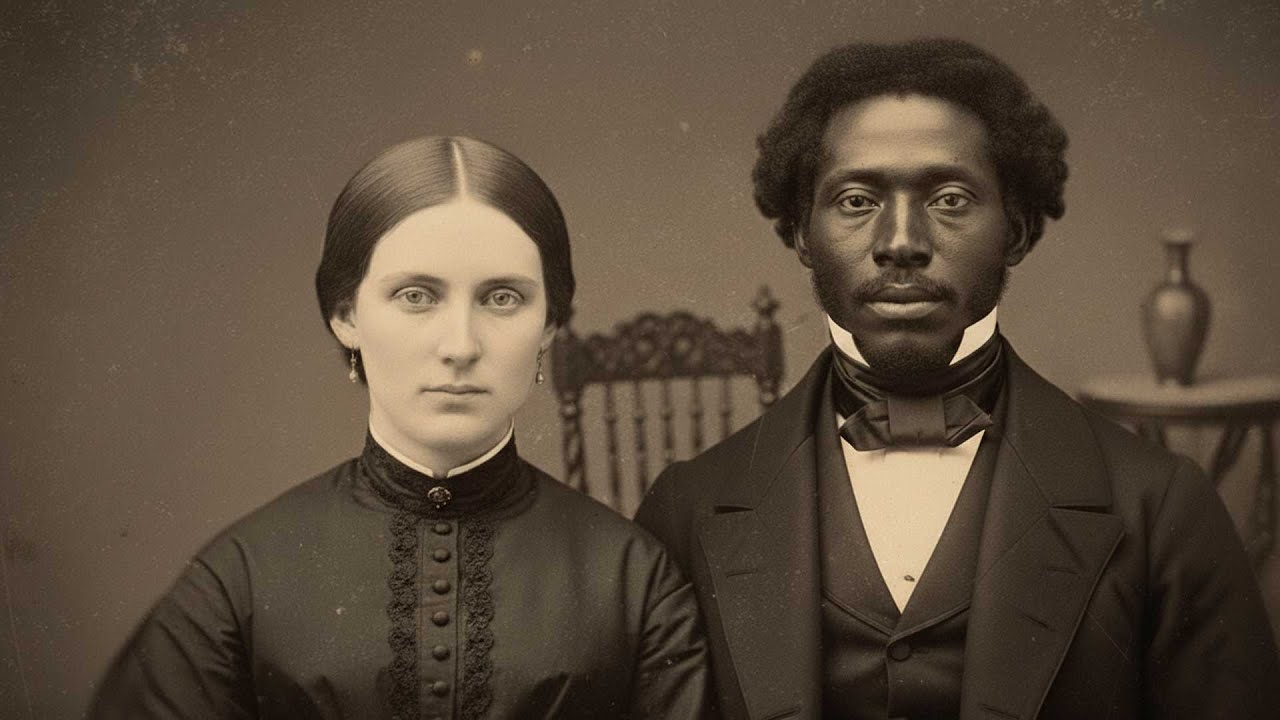

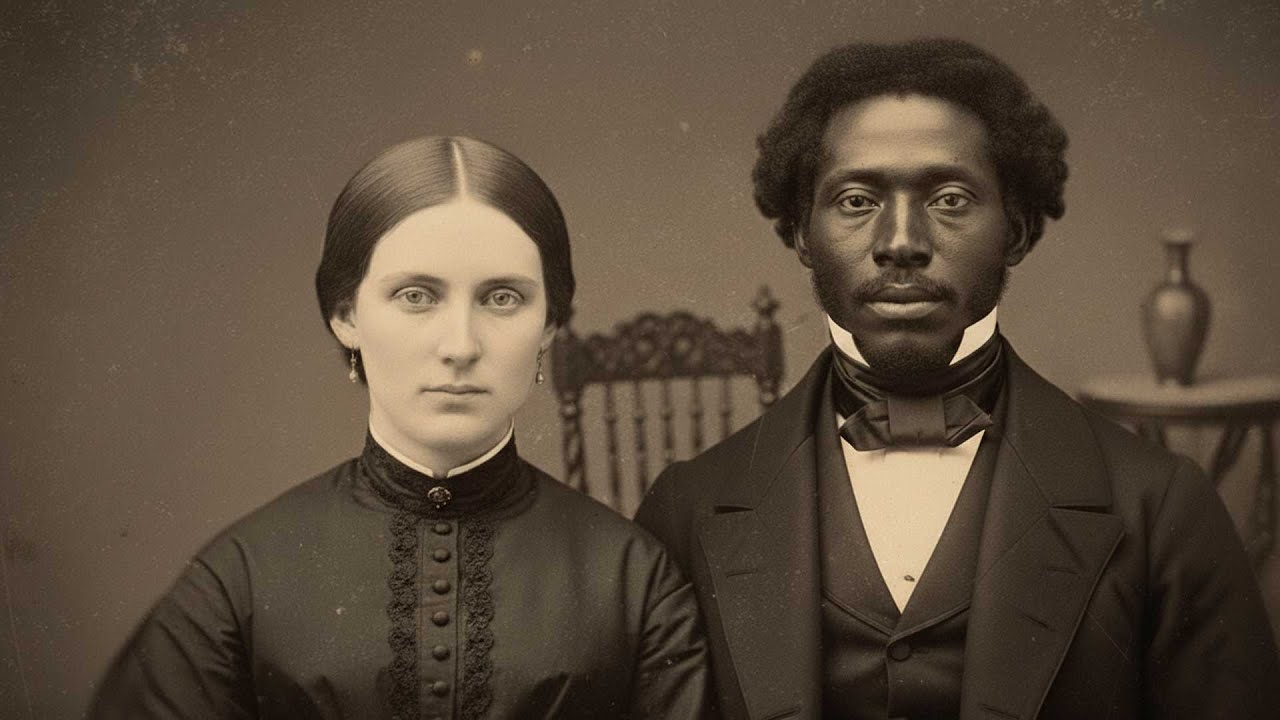

At 47 Trad Street, a house distinguished by its Bermuda stone façade and unusually high garden walls, the Ravenel family lives in cultivated comfort. Edmund Ravenel, a rice planter and gentleman of standing, presides over vast holdings—eight thousand acres, three hundred forty-two enslaved people—his reputation burnished by the praise of newspapers and the quiet approval of Charleston’s planter aristocracy. His wife, Katherine Rutledge Ravenel, is twenty-six years old, married seven years, and marked by the loss of three children who did not survive infancy. In the language of society pages, she is described as reserved, delicate, retiring early due to nerves—a woman whose sorrow is noted but never truly spoken of.

The household at Trad Street includes eleven enslaved people, among them a woman named Ruth, age twenty-three, listed in Edmund’s property ledger as “house servant, personal attendance, literate.” The notation is unusual. Literacy among enslaved people is rare, and Ruth’s ability to read and cipher sets her apart, suggesting a role within the house that is both privileged and precarious.

The first hint that something is different in the Ravenel house appears in letters between Katherine and her sister, Margaret. Katherine writes of strange sounds at night, scraping and weeping from below the kitchen house. Edmund dismisses her concerns—“merely the wind,” he says, or rats in the foundation. Ruth, gentle and attentive, tells Katherine that grief has made her hear things that are not there. She reads aloud to her mistress, sits with her in the afternoons, and becomes, in Katherine’s words, “the only person who seems to see me as something other than a problem to be managed.”

Their relationship deepens. Katherine’s journals, seventeen volumes preserved in the South Carolina Historical Society, document a growing dependence. Ruth comforts her, walks with her in the garden, shares stories of her own mother—sold away when Ruth was nine years old. “You survive by feeling in smaller portions, carefully measured,” Ruth tells her. Katherine, shattered by her own losses, finds solace in these conversations, drawing parallels between her grief and Ruth’s, sensing—dangerously—the ways in which their positions, though separated by law and custom, might share a kind of kinship.

But Ruth’s kindness is not simple. Letters she wrote but never sent, discovered hidden in the floorboards decades later, reveal a more complex truth. “The white woman cries to me as if I am her sister,” Ruth writes to her mother. “I hold her hand and make sounds of comfort, and inside I am laughing, and also I am crying, but not for her.” Ruth understands that her survival depends on her usefulness, on cultivating Katherine’s trust, on managing the delicate balance between intimacy and self-preservation. “Maybe friendship between slave and mistress is possible,” she writes, “in the same way that friendship between rabbit and fox is possible in the moment before the fox gets hungry.”

Beneath the surface, something else is happening. Ledger books recovered from the Ravenel estate show payments for foundation repairs, cellar modifications, metalwork, and late-night freight deliveries—entries that, when examined closely, suggest construction work being deliberately obscured. In the spring of 1839, Edmund pays contractors to modify the cellar, but the invoices are missing, the details vague. Katherine, increasingly obsessed with the sounds from below, descends to the cellar and finds new brickwork, a locked door she does not remember. Ruth, when questioned, becomes strange and sharp, warning Katherine to leave well enough alone.

The tension between the two women grows. Ruth’s interests visibly diverge from Katherine’s, and the intimacy that once brought comfort now breeds suspicion and fear. What Katherine cannot know is that Edmund has converted part of the house into a holding facility for illegally trafficked human beings—enslaved people smuggled from Cuba in violation of federal law, held in darkness beneath the house while paperwork is forged to legitimize their sale.

Fire brigade records, shipping manifests, and the testimony of a German immigrant firefighter named Hans Dietrich all point to Edmund’s involvement in a criminal network operating with impunity. Chains, manacles, iron masks—restraints for human beings, not farm equipment—are discovered in his warehouse. Ships arrive from Havana with “agricultural equipment” far too heavy and carefully packed to match their descriptions. Historians later confirm that Edmund’s activities were part of a larger network, protected by powerful men and tacitly tolerated by local authorities.

Katherine, piecing together the evidence, confronts Ruth. The confrontation is devastating. Ruth weeps but does not deny her complicity. “You think you would behave differently in my place?” she asks. “You survive how you can, and you judge no one else’s survival because you have never had to make choices with nothing but bad outcomes.” Ruth’s survival has depended on managing Edmund’s secrets, on keeping Katherine ignorant, on navigating a moral landscape where every choice is constrained by violence.

Unable to reconcile what she has discovered, Katherine breaks the lock on the cellar door. What she finds are brick-walled rooms, chains fixed to the walls, buckets, straw on the floor, and three people—two women and a boy—filthy, malnourished, terrified, and unable to communicate. She flees upstairs, physically ill, and is found by Ruth, who becomes frantic, urging her to pretend ignorance. “You are finally dangerous to me instead of useful,” Ruth says, and the fragile bond between them collapses.

Edmund discovers the broken lock and responds with violence. Katherine is beaten, confined to her room, and forbidden contact with anyone except a servant who brings her food. Ruth is ordered to clean and resecure the cellar, to arrange for the immediate transport of the captives, to ensure no evidence remains. In her testimony to a magistrate, Ruth describes Edmund’s threats—if word gets out, she will be sold to a rice plantation where the work kills slaves in three years. Her usefulness is her only protection.

For three days, Katherine remains locked in her room, writing furiously, documenting everything she has discovered, hiding pages throughout her room, and sending a desperate letter to Margaret. “If something should happen to me, please search thoroughly,” she writes. “Do not let them say I was simply mad.”

On the night of September 9th, 1839, the Ravenel house catches fire. The blaze begins in the cellar, spreads rapidly, and traps Katherine in her room, which has been barricaded from the outside. Edmund and the house servants escape; Katherine perishes in the fire. The official story is a kitchen accident, but fire brigade reports and Ruth’s later testimony tell a different story. The fire was set deliberately, accelerants used, Katherine’s door blocked.

Three days after the fire, Ruth gives testimony to the magistrate. Her words have no legal standing—she is property, not person—but they are recorded nonetheless. “Mr. Ravenel became aware that his wife had discovered illegal activities,” she states. “He told me on the morning of September 9th that he was resolved that she would not leave Charleston alive to speak against him. That night he gave me a bottle of laudanum and told me to ensure Mrs. Katherine drank enough to sleep deeply. I did this. Then Mr. Ravenel moved furniture against her door. Then he ordered me to go to the cellar and set a fire using lamp oil and straw. I did this. I set the fire because I was afraid he would kill me if I did not. I set the fire that killed Mrs. Katherine.”

The magistrate, bound by law and custom, cannot admit Ruth’s testimony as evidence, but he notes the details and recommends further investigation. The investigation never happens. Edmund is cleared of wrongdoing, Ruth is sold to a plantation in Louisiana, and the ruins of the Ravenel house are cleared, the lot sold, and a new structure built.

Margaret, determined to preserve her sister’s story, searches the ruins and recovers Katherine’s hidden journal pages. She hires an investigator who confirms Edmund’s involvement in the trafficking network, documents the use of the cellar as a holding facility, and reveals that Ruth managed the logistics of feeding and cleaning, functioning as a jailer to people as enslaved as herself. The report is filed away, ignored by law enforcement, and forgotten.

Edmund continues his business, remarries, fathers children, serves on the board of the Bank of Charleston, and is elected to the state legislature. His obituary calls him “a gentleman of the old school,” with no mention of Katherine, the fire, or the suffering he caused. Ruth appears in Louisiana plantation records for seven years, then escapes in 1846. No record exists of her recapture; she vanishes from the documentary record, her fate unknown.

For more than a century, the story survives only in fragments—letters, journals, testimony, scorched pages hidden in hatboxes and chair cushions, bones buried in unmarked pits beneath Charleston’s streets. In 1923, the South Carolina Historical Society receives Katherine’s journals, and a young archivist begins to piece together the evidence. The story is published in 1934, largely ignored, but preserved for future historians.

In 1974, urban renewal excavations uncover the remains of the Ravenel cellar—brick-lined rooms, rusted chains, grates in the ceiling, and dozens of human bones in an unmarked pit. The site is designated a historical landmark, a plaque installed to commemorate the suffering that occurred there. In 2003, renewed attention is brought to the case through research into Charleston’s illegal slave trade. In 2018, a graduate student reconstructs Ruth’s life, arguing that her story is essential to understanding how slavery functioned through coerced participation, forcing victims to become accomplices or face destruction.

The most recent discovery comes in 2019, when archaeologists find a sealed room beneath the Trad Street site. Inside is a wooden box containing Ruth’s letters to her mother and a journal of her own—twenty pages documenting her daily life, her management of Edmund’s trafficking operation, her cultivation of Katherine’s dependence, and her internal struggle with the choices she is forced to make. “Catherine called me her friend today,” Ruth writes, “and I wanted to scream at her that we cannot be friends because she is free to walk away from this house, and I am not. Because her kindness to me changes nothing about my captivity. Because she eats food prepared by people who are enslaved and sleeps in a bed made by people who are enslaved and lives off wealth created by people who are enslaved. And calling one of us her friend does not make her innocent. But I did not scream. I smiled and held her hand and told her she was dear to me. And maybe that was true. Maybe I did love her in some broken way. Maybe love can exist even in configurations of power that corrupt everything they touch. I do not know. I only know that when she finally sees what is underneath this house, she will hate me. And I will have lost the only person in this place who ever spoke to me as if I were human. And I will have lost her because I chose survival over honesty. And I do not apologize for that choice because I am still alive and that is all I have.”

Her journal ends abruptly in early September 1839, just before the fire. The last entry reads, “He has decided what to do about Catherine. I know what is coming. I have to choose whether to be part of it or die with her. This is what slavery is. Not just being owned, but being forced to destroy others to survive. I will do what I must. I will live with it if I live at all. And someday, somehow, I will be free of him.”

Today, the Trad Street site is part of a walking tour focused on Charleston’s suppressed histories. Guides talk about the trafficking network, about Katherine’s doomed attempt to expose it, about Ruth’s impossible position, and about the people whose bones were found in the cellar pit—people who came from Cuba or other parts of the South, held in darkness and then disappeared, leaving almost no trace except the physical evidence of their suffering. Local historians estimate that hundreds of people may have passed through Charleston’s illegal trafficking network in the decades before the Civil War, held in cellars and attics and warehouses while paperwork was forged to legitimize their sale.

The buildings on Trad Street are beautiful. The gardens are lush. Tourists take photographs of the ironwork and pastel-painted houses and cobblestone streets. Beneath it all, beneath the beauty and the history and the careful preservation of architectural heritage, are rooms where people suffered while their captors slept above them, certain of their impunity, protected by laws and social structures that valued property over human beings and white men’s reputations over anyone’s life.

Katherine Ravenel tried to act against that system and was murdered for it. Ruth navigated it using every tool she had and was still destroyed by it, though she may have managed to escape. And the people in the cellar, whose names we do not know, died as property rather than persons, their existence recorded only in the chains that held them and the bones that remained after they were gone.

This story is not exceptional. It is representative. What makes it knowable is only that enough evidence survived—letters, journals, testimony, and physical remains that could not be entirely erased. How many other houses in Charleston, in New Orleans, in Richmond, in every city and town where slavery thrived, held similar secrets that left no trace? How many women realized too late what they were living alongside? How many enslaved people were forced to choose between complicity and death? How many crimes were committed with absolute confidence that they would never be prosecuted, never even be acknowledged, never disturb the social order that depended on not seeing, not knowing, not speaking what everyone understood was happening?

The past is not the past. The house on Trad Street was rebuilt, but the rooms beneath it remain, now excavated and documented, but still there, still holding the memory of what happened in them. Ruth’s letters exist in an archive where anyone can read them. Katherine’s journals can be requested by researchers. And somewhere in the ground beneath Charleston, there are bones still waiting to be found, belonging to people whose names are lost, but whose suffering was real, and whose existence demands to be acknowledged even now—especially now, when it would be so much easier to tell only the beautiful stories about history and leave the horror buried where no one has to look at it.

But we are looking. We are reading the documents. We are excavating the sites. We are speaking the names we know and grieving the names we do not. We are saying that Katherine Ravenel died because she could not tolerate complicity. We are saying that Ruth survived because she did what she had to do, and that her survival was a form of resistance even when it required terrible compromise. We are saying that the people in the cellar were human beings who deserved to be remembered as more than victims, as people with histories and futures that were stolen from them by men who faced no consequences.

And we are asking, as we must always ask when we look honestly at history, what are we living alongside right now that we are choosing not to see? What cruelty exists beneath the surface of our own ordinary lives? What will people a hundred years from now say about our refusal to acknowledge it?

The story of the master’s favorite slave who became his wife’s only friend and then her enemy is not just a story about 1839. It is a story about power, complicity, resistance, and the terrible choices forced on people who live in systems built on violence. It is a story that asks us to look at what we would rather not see, to acknowledge what we would rather deny, and to remember that silence and ignorance are also choices, and that they have consequences that echo forward through time long after the people who made them are gone.

The house on Trad Street burned, but the story survived, and that matters.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load