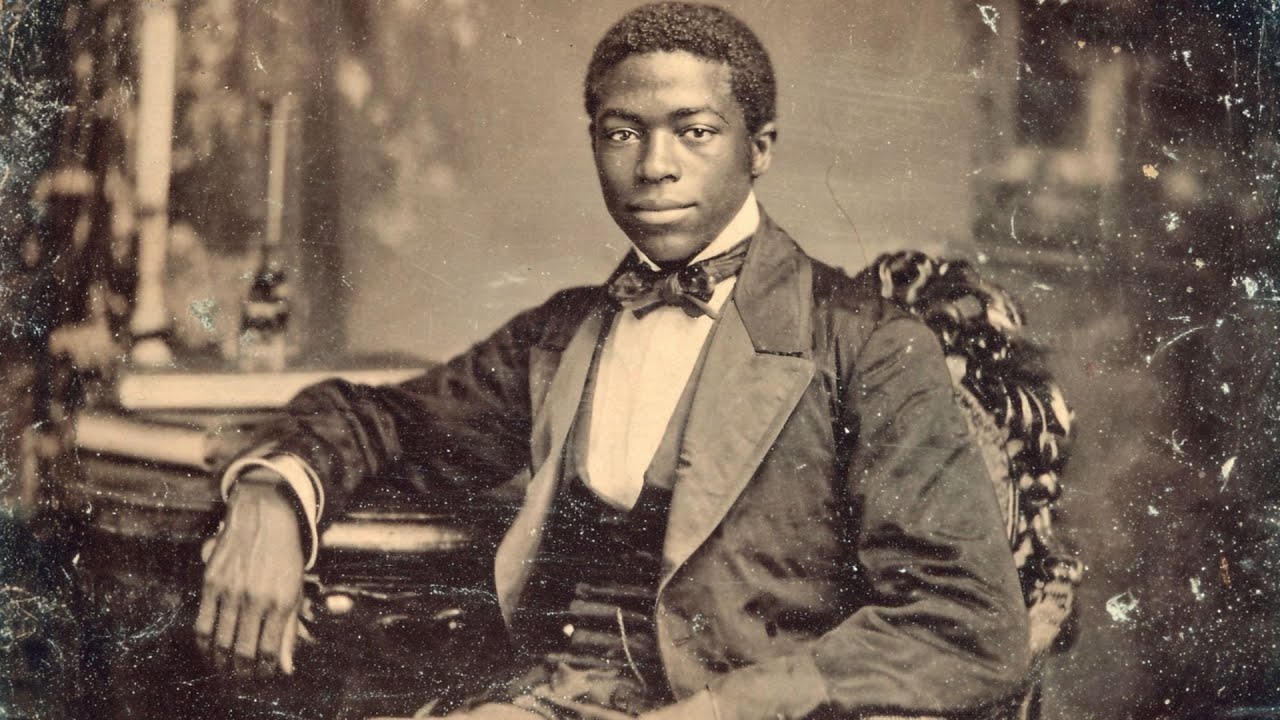

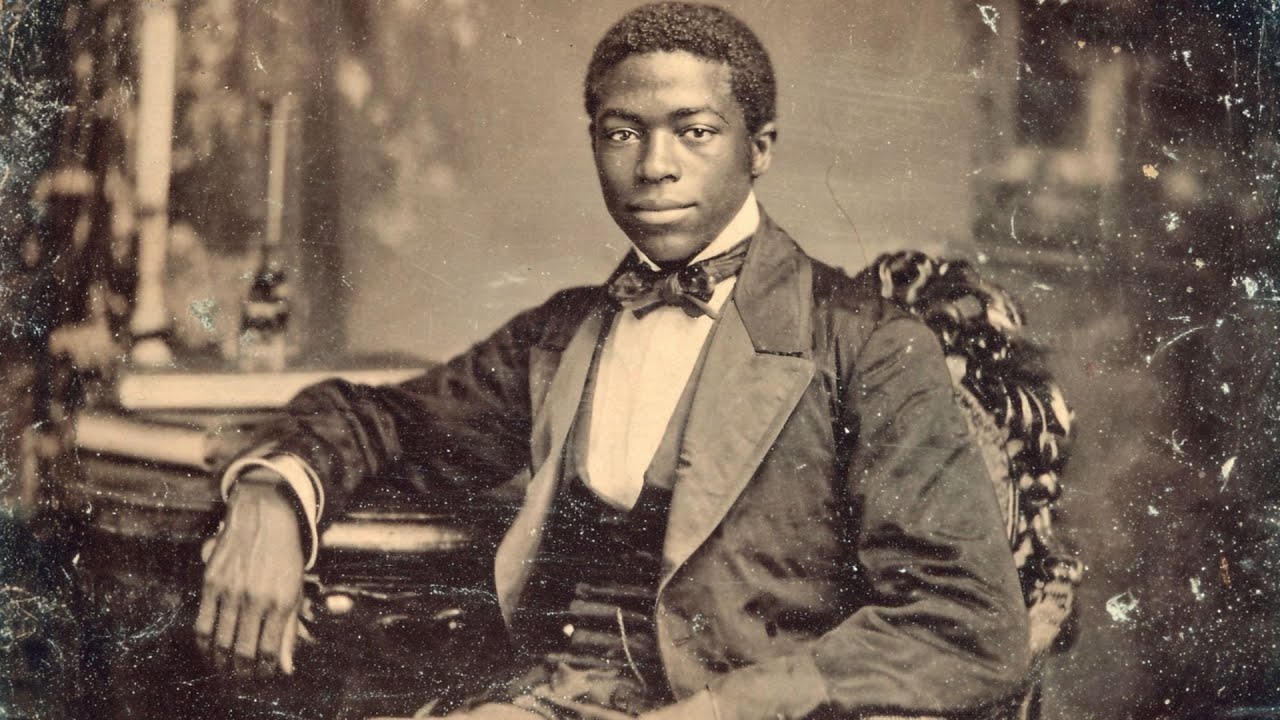

They found the portrait in a church basement in Maryland, wrapped in a wool blanket that had learned the damp, and forgotten the sun. A smiling boy, somewhere between nine and twelve, coat a little too big across the shoulders, hair tidied with the earnestness of someone who wanted to be taken seriously. He had the soft, defiant brightness of children who’ve been told to hold still and can’t quite stop their joy from leaking into the corners of their mouths.

The frame had cracked along one edge, and a thin web of age had settled over his face like a whispered promise. There was no name scratched on the stretcher, no plate brassy as a proclamation. Only penciled numbers, a ledger mark in a hand that had done this before. People lifted the painting and smiled back without meaning to. “Who is he?” someone asked. “A donor’s child?” someone guessed. “Maybe a student from when the parish ran a small school?” another said, hopeful. The caretaker shrugged. The blanket had been labeled Misc. Portraits, as if the past could be made harmless by abbreviation.

The truth arrived the way truth often does in the United States: politely, on letterhead. An archivist in Annapolis wrote to say she’d come across a church inventory from the 1890s mentioning a painting of “the boy Samuel,” donated by an older parishioner with instructions that it should hang “someplace where the light is kind.” Attached was a photocopy of a second document: a brief, cramped entry in an estate book from 1861 identifying “one boy, Sam,” valued at three hundred dollars and transferred upon death to “the widow’s care.” The ink pressed hard into the paper, the numbers tamped down like something someone wanted to convince themselves of.

A historian held those two slips side by side, the smiling child and the sum, and felt a now-familiar nausea: the American talent for turning lives into columns, then asking the eye to skip to the next line. It would have been tempting—comforting—to treat the portrait as an orphan artifact, a sweet reminder of some unnamed past affection. But the paper had other ideas. It wanted to be read the way the land itself sometimes wants to be walked: carefully, with attention to where the ground dips and why.

The parish opened its records; the county did too, once the historians knew what to ask for. There were baptism rolls with gaps, business ledgers with their arithmetic in order, and the shadows of people passing through the accounts like breaths you could fog on a winter window if you could get close enough. In the end, the line that bent toward the smiling boy started, improbably, with a woman’s will and a receipt for a hand-painted coat.

The will belonged to a Mrs. Ruth Whitaker, who died in 1897 at a respectable age and with respectable assets: a rowhouse on a hill with a view of the harbor; a small box of gold coins; a loom that had been her grandmother’s. In a list of bequests that were otherwise unremarkable—tea services to nieces, quilts to friends—she wrote that her portrait of “Samuel, my first charge, as a boy” should be given to the church with her love. “He was born in bondage,” she added, “and saved me from being the kind of woman I might otherwise have been.”

There it was: a sentence like a window flung open in a room you didn’t know was stifling. Born in bondage. And saved me. The historians read the line again, then again, and felt the way the present sometimes tips to reveal the river running under the street. A receipt pinned into Ruth’s account book, dated 1854, recorded payment to an itinerant painter—“a coat for the boy; likeness for his mother.” The painter had charged extra for travel to the “quarters,” the shorthand that turned homes into compartments. He’d been hired, apparently, to make two portraits: the coat and the boy. Only one had survived. Or rather, only one had been saved.

There was less mystery, after that, and more labor. They found the bill of sale that brought a woman named Dinah and “her infant son Sam” to the Whitaker household in the spring of 1844. They found the ledger entries that tracked clothing, shoes, food, blankets, doctor’s visits—inventory bars masquerading as compassion. They found a baptism record in which the infant’s name was written as “Samuel (mother Dinah; father unknown),” followed by a parenthetical added in a different hand: “as for the father: known but unrecorded.” The kind of bureaucratic mercy that did not require the priest to write the master’s name down even if everyone knew it. The paper’s second language was omission.

But the portrait insisted on presence. The boy’s eyes made it difficult to pretend he didn’t know what was happening around him. His mouth tilted toward a laugh he’d negotiated with the painter. In the corner of the frame, barely visible under varnish, someone had scratched a date into the wood: 1855. That would have made Sam around eleven in the portrait, still young enough to play tag in the alley, old enough to run messages to the harbor and come back with stories learned from sailors who had more words than money.

One entry in Whitaker’s book mentioned that “the boy has learned his letters from the youngest Miss,” as if literacy were a trick slipped under a locked door. Another described a day when Dinah had stayed in bed with fever and Sam had carried water and firewood without being asked; Mrs. Whitaker noted it as if it were a business asset proving itself productive. But then, a single line, out of place in its tenderness: Sam laughed at the painter’s silly face, and the room felt brighter. I wish he were mine to keep.

The historian reading that line closed the book and went for a long walk under a sky that was trying to decide whether to rain. It’s a particular American ache, to stumble on tenderness housed in a system that defines the tendered person as property. If the portrait had been painted of a boy legally free, it would still have been beautiful. But the law at the time—a Maryland law, in the decade before the war—would have seen the boy as Dinah’s child and therefore as the estate’s asset, his smile subject to valuation, his future bound to someone else’s debts.

There were other documents. There always are. A sheriff’s report about a “disturbance” on Whitaker’s street in the summer of 1856, when some of the men from the shipyards got drunk and loud, and Sam, now tall for his age, was seen calming a horse that had bolted. A list of church donors from the same year in which “Mrs. Ruth W.” pledged an extra five dollars “for the education of the colored children,” a thing she would not have called radical but would have done anyway. A bill for quicklime after a fever season—common enough in those years—and a note from the parish priest lamenting “the burdens the Lord has placed upon the mother Dinah,” who had lost two infants in a row before Sam.

Then the country broke, and the paper shifts. The year 1861 arrives, and the estate book reduces Sam to a dollar figure again, cold and efficient, as if his life could be tidied by arithmetic. The historians stared longest at that page, not because it told them something they didn’t know, but because it told it in a hand so impassive it might as well have been stone. The widow’s care. Whatever that meant. The widow’s moral accounting does not speak in the ledger. The ledger has no room for such words as saved me.

The war years are jagged in the surviving records. Maryland sat on that uneven seam between North and South, and the law there swayed with the winds of armies and the wills of lawmakers who wanted to thread a needle between what was right and what was profitable. Slavery in Maryland ended early, comparatively, in 1864, and that legal pivot is a hinge the portrait swings on, a subtle change of light. In 1865, a small note appears in parish minutes: Samuel reads one of the Psalms aloud during Sunday school, “with clarity and feeling.” Another: “S. Whitaker, formerly a servant, now in employ as a porter at the wharf.” Formerly. The word does a lot of work in so little space.

By then, the boy in the portrait would have been a young man who could lift more than a barrel and less than a ship, who could read letters delivered to the wharf and write quick notes for sailors to carry home to Baltimore or Norfolk or farther still. He’d have known how the wind tastes before a storm and how rumor travels faster than the tide. He might have known the abolitionists only as a rumor and emancipation first as a rumor and then as a morning with different light.

A photograph from the late 1860s shows the parish picnic spread under a cottonwood tree, pies on tables, mugs sweating in the heat. The caption lists names, as captions do, and then “others.” That’s the thing about photographs of the era: they can show you how people stood and who looked at whom, but they almost never tell you everything. If Sam is in the picture, he is one of the “others,” a category that carries both the weight of centuries and the shrug of laziness.

What the portrait can tell us—and all good portraits lie less than most records—is the way this boy wanted to be seen. The awkward proud set of his shoulders. The hand turned just so, not clenched, not idle. The smile that dares you to underestimate him. Whoever he became after the paint dried, he once stood in front of a person with a brush and insisted on joy. That insistence should count for something in a country that has made a habit of pretending that survival is unremarkable.

There was, in the box of Ruth Whitaker’s things, one more item that made the historians sit back in their chairs. It was a letter, written late in her life, to a friend who had moved west. The handwriting was shaky and the grammar tender around the edges. “You remember the boy,” she wrote. “He saved me when I was young and not good. I mean, not brave enough to be good. He had a way of smiling that made me confess things to myself. After the war, he came back from the docks one Sunday in a clean shirt and told me he was courting a girl who laughed faster than he did. I gave him the portrait then, because it was never mine. He told me I should keep it, because I needed the reminder.”

That line changed the painting in the room, even before anyone moved it. It changed the story of ownership that had been actual ownership in 1854 and had at least partially turned into responsibility by 1865 and something else entirely by 1897. The portrait had done its quiet work for Ruth: reminding her what safety felt like, reminding her who she had been and who she’d decided to be instead. It had become, of all impossible things, a kind of conscience. And now it was on a table in a church basement, looking for a wall.

If this were a fairy tale, the historians realized, the boy would be revealed to be a prince lost at birth and returned to his rightful place. But the United States does not produce fairy tales like that; it produces something sterner and, in its way, more miraculous: lives that swell beyond what the law imagined for them. They found a marriage record for a Samuel W.—the surname a tangle of choices, Whitaker perhaps taken as convenience or gift. They found a birth record for a daughter named Miriam, and a business listing in a local directory where “S. Whitaker & Son” offered hauling services from the wharf to the mills upriver. They found a newspaper note from 1889 calling Samuel “a familiar and welcome face along the waterfront.”

What they did not find was a flawless road. Two years of illness in the mid-1870s reduced the hauling business to debt. The marriage record was followed by a death record; Miriam died of fever just after her fifth birthday. The former mistress sent soup; the parish sent prayers. Samuel moved twice, then back again, his name appearing at slightly different addresses like a small boat tying up at different posts along the same stretch of water. Life rarely lets anyone—anyone at all—keep what they love without cost.

And yet the portrait endured. When the church, in our time, finally hung it where the light is kind, the day was American in the way the best days are: messy in its logistics—someone forgot the nails; the ladder was too short; the microphone failed—and plain in its beauty. People from the neighborhood came, and people for whom the neighborhood had once been home came back, and people who’d never been to a church before stepped inside and looked up and found themselves looking at a boy whose smile knew more than it said. There were readings—of Scripture, yes, and of the historian’s careful narrative—and there were moments of silence that were not empty but full of names not recorded and hands not photographed and voices that had been told to hush.

A descendant of Ruth’s stood and cried without apology. A descendant of nobody anyone could name—the descendant of people whose names were replaced by job titles and line items—stood and looked at the boy for a long time and said, “I know that smile.” Outside, a truck rattled along the street, the way trucks have rattled along American streets since there were trucks. Inside, a little girl on a chair tiptoed to see better and waved, just in case he could see her too.

It would be easy to say that the portrait offers closure. That’s a word we like. It goes down well in grant applications and pastor’s notes and newspaper pieces turned in by deadline. But the truth is not closure. It’s something more useful and more demanding: connection. The painting answers the question “Who is he?” with a cascade of other questions we have to keep asking in every American room: Who decided it was safe to call him property? Who taught him to read when the law said he shouldn’t? Who made sure there was bread on the table and a clean shirt for Sunday? Who stood between him and the world when the world narrowed? Who stood with him when the world widened?

The portrait is a mirror that refuses to forget it’s also a window. It invites the eye to come close and then makes the eye look out beyond the frame, along the street where the docks used to be, toward the water where ships once coughed coal into the air and now leisure boats make arcs like question marks. It asks you to hold in one gaze two truths that the country has spent a long time trying not to reckon with: that a child can be adorable and accounted for as property at the same time, and that the accounting is as obscene as the adorableness is undeniable. It asks you to stay with the discomfort long enough to let it work on you.

There’s a temptation to rescue the past with sentiment, to turn every hard thing into a lesson and every lesson into a reassurance. The portrait resists that. The boy’s smile is not a pardon for anyone. It is a statement of presence. It says: I was here. It says: You cannot say you didn’t know, not anymore. It says: you have to decide what you will do with the knowledge that a country you love—and it is possible to love this country, as complicated and stubborn as it is—once wrote a price next to a child’s name, and then wrote another word next to it: saved.

Saved. The word in Ruth’s letter does not mean rescued, not only. It means spared from becoming a certain kind of person. It means turned, gently, by another’s humanity. In that sense, the boy in the portrait saved more than one person; he saves, in a small and continuing way, everyone who stands beneath the frame and lets their chest loosen around the old habit of denial. He saves by insisting on being looked at as a person, not a symbol. He saves by forcing us to consider what we owe to those whose names were left off the invoices and who nonetheless carried water and wood and whole households on their backs.

It is a very American thing to hang a picture and hope it will do the work of honesty for us. It won’t. But it can remind us to start. The historians did their part by piecing paper into a life; the church did its part by making space on the wall and in the room; the neighborhood did its part by coming and listening and telling stories that had survived in kitchens and on stoops and in the murmurs of people who were not allowed to write their memories down. The rest is on the living.

Before they left that first day, after the picture was hung, one of the historians took a small, respectful risk. She wrote a label that did not pretend objectivity is the same as neutrality. “Samuel (called Sam),” the card read, “painted circa 1855. Born into slavery in Maryland. Baptized here. Later a porter on the waterfront. Husband. Father for a time. Beloved by those who knew him. His likeness was commissioned by a mistress who became, over time, a friend. The painting hung in her parlor as a reminder of who she might have been and chose not to be. It hangs here now so we remember who we might be, and choose.”

On the way out, the building smelled like lemon oil and old wood, like a ship that had been scrubbed and repaired and was ready to sail again. On the steps, the light was kind, as if Ruth had arranged it. The street below was ordinary in the ways American streets often are: kids on bikes, the thud of a basketball on pavement, a woman with groceries tucked into the crook of her arm, the sound of a radio turned up for a favorite song. The historian thought of the boy, the smile that had set a room right more than once, and she wondered whether he’d known, in the quicksilver way bright children often do, what the painting would do in the world long after he was gone.

He probably didn’t. He probably just liked the attention, the way the painter made faces to coax out a grin, the way his mother’s eyes shone when she saw him turned into color and light. But that is how history works here, in this place that can be so hard on bodies and so generous with second chances: ordinary days seeded with moments that don’t feel like anything at the time, then come back decades later with their hands full. A portrait no one labeled. A letter folded into a book. A will that thought ahead. A smile that turned into a doorway.

Someone will stand under that portrait next week or next year and see their own child in that boy, or see their younger self, or see a person they loved and lost. Someone will decide to look up a name and find three more. Someone will write, in careful ink, on modern paper, the words the pastor used that day that made something inside their chest ease and ache at the same time. Someone, standing at the edge of the room where the light falls best, will feel the subtle tilt that happens when a story finds its listener.

The boy in the painting will keep smiling. He will keep insisting that we remember the difference between inventory and identity. And the United States, with its long memory and its long history of trying to forget, will keep offering us rooms like this one, small and luminous, where we can practice telling the truth. The truth is that he was born a slave and loved as a boy, a son, a future man. The truth is that people changed because they loved him and that he changed because people loved him back. The truth is that a painting can be a promise if we let it be.

In a country that paved over so many names, it matters to gather under a frame and say one out loud. Samuel. It matters to name the mother—Dinah—whose labor is everywhere and whose signature is nowhere. It matters to notice how the light lies across his cheek and how the brush caught the stubborn set of his chin. It matters to feel the tug of pride and grief and anger and gratitude all at once and not rush to tidy them. It matters to take a breath and then do the next right thing: teach, learn, vote, show up, keep the room open, keep the light kind.

They found a portrait in a church basement and thought, at first, that they’d found a sweet curiosity. What they found, instead, was a door. When you step through, the air on the other side feels different. Lighter, somehow. Not because the past is suddenly easier, but because the present is suddenly truer. The boy’s smile meets you there, just as it did on the day he stood too straight in a coat too big and decided to give the painter nothing but joy. It has a way of making you confess the things you’ve been putting off. It has a way of making you braver. It has a way of reminding you that we are always, all of us, both the keepers of the ledger and the keepers of the light, and that it is never too late to choose which one we want to be.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load