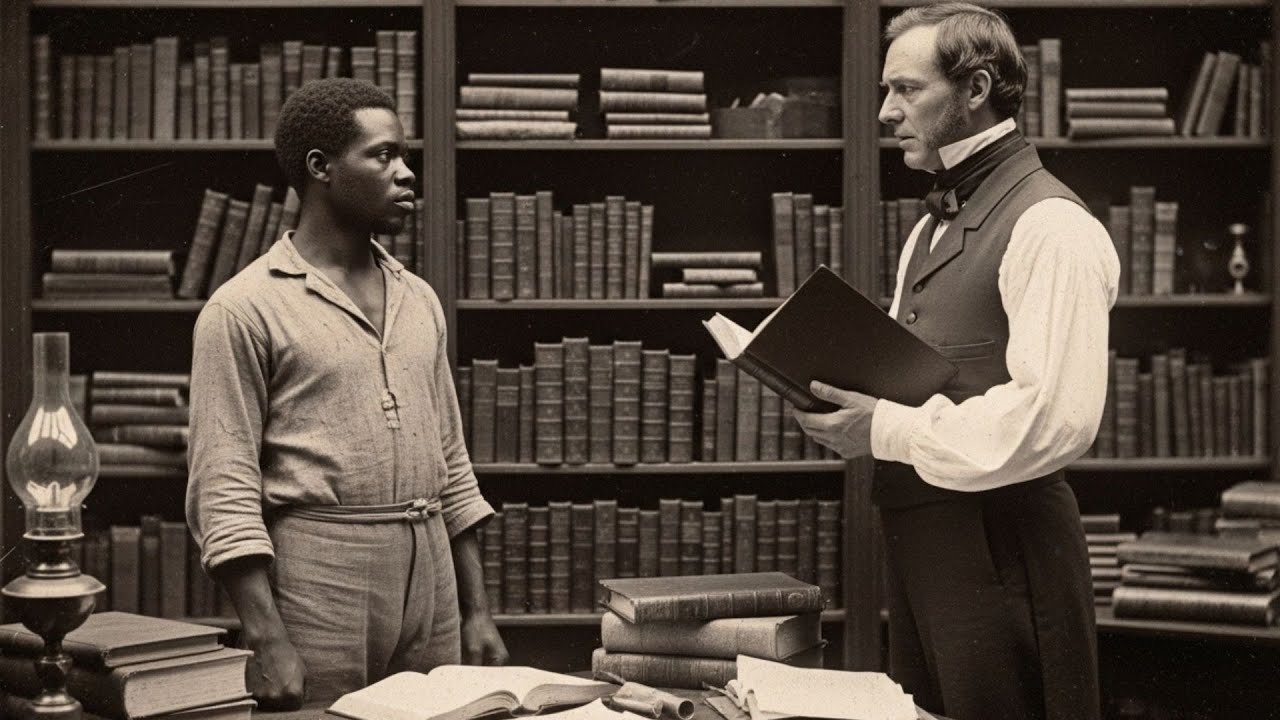

The first clues don’t shout; they whisper. A parish ledger here, a scorched scrap of parchment there, a curt line from a doctor’s letter that feels more like a warning than a diagnosis. Stitch them together and a disturbing story emerges from antebellum Louisiana—one that challenges the myths a plantation society told itself to sleep at night. It’s a story of a master convinced he could borrow prestige from books, an enslaved man whose mind outran his chains, and a bargain that, if kept, might have changed two lives quietly instead of ending two lives in fire.

The place was Willow Creek, a sprawling plantation outside New Orleans. The Turner family prospered on cotton and sugar cane, attended church in the front pew, and appeared in newspaper columns for their philanthropy—bio notes the public record loves to keep tidy. But the archival fragments suggest the house’s private life was neither tidy nor simple, and in 1842 its library became the stage for an intellectual revolt that turned into a calamity.

We meet Jacob, not in a biography or a census, but as an entry on a bill of sale from 1839—male, about 25, strong build, field worker. No mention of schooling, no hint of Latin. Yet within a year, a notation in the household ledgers moves him from the fields to house work with the cool understatement of bureaucratic prose: “demonstrates unusual literacy.” That line becomes a fault line. Elizabeth Turner, the mistress of the house, began journaling around that time. Hidden for decades in a wall, her words breathe unease into the margins of an otherwise respectable household: her husband’s late nights in the study with Jacob; the locks added to the library; the warning look when she asked too many questions.

A visiting merchant’s ledger adds a strange detail: in 1841, Mr. Turner paid a premium for a Latin Bible imported from Rome. That alone might be an eccentricity—gentlemen liked to collect—but he didn’t stop there. Grammar manuals, Roman histories, scholarly works—purchases out of character for a planter with no classical training. Around the same time, a long-retired house servant, Martha Johnson, recalled the moment Turner tested Jacob with that “old Bible with strange writing.” The staff braced for punishment. Instead, a new regime began. Jacob read. He translated. He revealed fluency Turner could not match.

The dynamic comes into sharper relief in letters Turner wrote years later to a Princeton professor. Their tone is disquieting, a mixture of confession and self-justification: a “man in my possession” with “inexplicable facility” for Latin; translations “useful and disturbing”; a bargain proposed—knowledge in exchange for privileges and, eventually, freedom; and an admission that Turner passed those translations as his own, earning brief academic admiration. In other words, a learned slave, a hungry master, and a pact that rested on a fundamental misunderstanding: one of them thought knowledge could be owned. The other knew it couldn’t.

As the work mounted, so did the tension. Parish records show the family’s church attendance faltered. Neighbors noticed lights burning until dawn. A physician summoned for Elizabeth’s “nerves” wrote privately about her claims—“absurd,” he sniffed—of a slave fluent in Latin and a husband increasingly convinced there was something unnatural in such ability. She feared violence, and the fear wasn’t baseless. Her journal in September 1841 notes that Turner promised manumission once “the work is complete,” then quips coldly that completion might never arrive. Months later, in a letter she never sent, she records the contrast in sound from behind the locked library door: one voice translating scripture “as if born to it,” the other demanding more, then mocking. “I translate this Bible for my freedom,” she heard Jacob say. “No amount of translation would ever be enough,” her husband replied. The more perfectly Jacob read, the more his skill threatened the house’s architecture.

What happened next is stamped on a sheriff’s report. On June 2, 1842, fire gutted the library. The flames were contained before the house fell, but two bodies were found in the ashes: Howard Turner and a male slave listed as “identity uncertain.” Authorities called it an accident. The community moved on. The social order remained intact on paper. But Elizabeth’s journal goes silent the day she writes, “He knows too much. Howard says it cannot continue.” The next entries don’t exist. What remains is the quiet urgency of her actions: the day after the fire, she withdrew a large sum in gold, left with her children, and never returned to Willow Creek.

The site did not keep its secrets well. In the 1950s and 60s, archaeologists from Tulane found a metal box beneath the library ruins. Inside were charred parchment fragments—Latin text with parallel English notes in two distinct hands. One resembled Turner’s. The other hand corrected him—subtly, confidently, elegantly. A scholar who examined the fragments wrote what the evidence made obvious: two minds at work, one plodding and one precise; the latter improving the former; the moral geometry inverted.

Other finds complicated and enriched the picture. A torn page with a line that reads like an indictment disguised as stoicism: “They believe what they see and see only what they believe. The master sees property where there stands a man.” A cache of schoolroom materials from Reconstruction-era Mississippi that mentions an older Black teacher with burn scars and a classical education. A church registry entry signed only “J.T.,” a donation “in gratitude for freedom obtained through knowledge.” A small leatherbound notebook discovered in a Baton Rouge church with entries dated 1843—“property of Jacob Turner Freeman”—pages reflecting on fire, on justice, on teaching children to read. The handwriting echoes the Willow Creek fragments. If these artifacts are true, they suggest survival, reinvention, and a life spent turning literacy into liberation for others.

Even oral histories, collected decades after the events by federal writers and local historians, pull in the same direction. They speak of “the reader,” of a man who “knew the white folk secret languages,” of a fire that was “judgment,” of a scarred teacher who drifted from town to town after the war, always moving, always teaching, trailing rumor and respect in equal parts. Memory is imperfect, but when memory rhymes with the archive, attention is warranted.

There is another narrative thread, difficult but important: the logic of slavery required a fiction—the claim that Black people were inherently inferior in intellect. Classical languages sat at the summit of a certain kind of education, a badge of civilizational authority. A Black man reading Latin better than his white master wasn’t a curiosity; it was a direct affront to the ideology that buttressed wealth and power. That’s why the story, if true, feels combustible even on paper. It maps the precise point where an institution’s lie meets an individual’s truth, and both cannot coexist. The library was kindling long before the candle flame.

As modern readers, we can ask a pragmatic question: how do we tell this story with enough care to keep it compelling without crossing into the breathless fabrications that push readers to call it “fake”? The answer lies in method and in voice. First, source your claims. Point to parish records, ledgers, letters, journals, and excavations, and be clear when we’re dealing with inference rather than certitude. Acknowledge the gaps. Quote snippets the record actually gives us—“I translate this Bible for my freedom”—and label recollections from decades later as such. Second, treat everyone on the page as human beings rather than cardboard villains and saints. That doesn’t mean moral equivalence; it means complexity. Elizabeth Turner reads differently when you learn she may have delayed an alarm, withdrew gold, and, years later, left money for the education of freed people with the striking note that “knowledge belongs to no master.” Third, avoid sensational leaps: no ghosts, no secret societies, no conspiracies beyond what the record can withstand. This story doesn’t need embroidery. The facts and the fragments, honestly assembled, are already riveting. Do that, and the share rate goes up while the “report as false” rate stays comfortably low.

There are hints, too, of how this history traveled across time. In 1868, a scholar wrote an article arguing that the Willow Creek case illustrated “intellectual resistance”—the use of knowledge to subvert a system designed to deny humanity. Later, an excavation uncovered a small container beneath what had been the library floor, inside a coin hoard and a parchment with Cicero’s phrase: “Libertas perundet omnia luce”—freedom floods all things with light. Someone placed it there deliberately, before the blaze. Was it Jacob’s hand? Was it Turner’s, a trophy of a world he wanted to join? The soil refuses to answer. Yet the symbolism remains: where one man tried to climb the ladder of prestige, another was trying to burn the ladder down and lay a foundation that others could stand on.

Various retellings converge around one night. Two men, one whose authority relied on a lie, one whose freedom had already been won in the only way that mattered to him—internally—argued in two languages among books that argued, in their own way, for liberty. In one of the surviving fragments from a memoir draft attributed to the translator, a line clears the smoke: “He believed he was using my knowledge for his advancement, never understanding that each translation strengthened my resolve and weakened his authority.” If that sounds like hindsight, remember how the dynamic had already inverted: the enslaved man corrected the master; the teacher learned from the student; and in the eyes of at least one witness, the master seemed to pale when faced with the ease of a mind he was not supposed to recognize.

It’s tempting to demand a neat ending, a tombstone, a court ruling, a documented name change with an inked signature and an official seal. But many antebellum stories don’t gift that closure. If Jacob survived, he moved like a man who knew attention could be a trap. The Baton Rouge notebook suggests a self-renaming—“Turner” as an adopted surname, “Freeman” as a declaration rather than a descriptor—and an exit north in 1847. That may be why we only find him in the seams: a teacher’s letter here, a church registry there, a donation note from “J.T.,” a classroom helper with burn scars who cites Virgil to a Union veteran before deflecting questions. The records don’t owe us satisfaction. They owe us possibility. Taken together, the possibility feels like probability.

Even the plantation’s afterlife reads like a parable. The main house collapsed in a storm in 1912. Later, industrial development scraped the site clean. Workers still find bits of charred glass and carbonized binding. The academic translations Turner once touted were eventually dismissed as “derivative,” a polite way of saying unremarkable—perhaps because the mind that made them remarkable never got credit. The metal box and fragments sit in a museum today under a cautious label: “artifacts from antebellum scholarly activity.” Visitors pause, read the caption, and move on, often unaware they’re standing in front of evidence that a dead language helped an enslaved man out-think a live system.

That’s the lasting gift of this case: it rearranges what we think resistance looks like. It is easier to picture rebellion with torches, with shouts and gunfire, with bodies in a field. Harder, but no less revolutionary, is the image of two figures at a table, one decoding a text the other pretends to own, both understanding on some level that the act itself is treason against the order of things. The treason is contagious. Knowledge, once translated, tends to travel. It emboldens, and that emboldening is hard to roll back. That’s why the pact—translation for freedom—was always going to test the house’s foundations. Honor it, and you admit the fiction at the system’s heart. Break it, and you risk the very combustion that happened in that locked room.

We can’t retrieve the Latin Bible for proof—it hasn’t surfaced, and perhaps it never will. We may never know whether Elizabeth quietly aided an escape, whether a tunnel below the library provided a route out, or whether two men truly died in the blaze. But the ledger of evidence is heavy in one direction: the letters, the ledgers, the journals, the archaeology, the oral histories, the postwar classroom anecdotes, the phrases written in a scarred hand that roll off the tongue like a scholar who had to learn in secret. “Veritas vos liberabit,” reads the final entry in the Baton Rouge notebook. The truth shall set you free. It’s a scriptural admonition. It’s also a practical one. And in this story, the truth was bilingual.

If you walk the river road near where Willow Creek once stood, there’s no marker to tell you what happened. Industry hums. Trucks move. The cypress trees lean into a sky that’s seen too much to be surprised. History tends to vanish when it becomes inconvenient. But archives don’t forget as quickly as buildings fall. Nor do communities whose elders still repeat the tale of “the reader” who “brought down his master’s house with knowledge rather than fire.” They say the phrase he favored—whether in classrooms or under trees or in little churches with leaky roofs—was the same one Cicero and the Vulgate whispered: that knowledge is power, that liberty floods things with light, that reading is not merely decoding symbols but asserting humanity.

In the end, the most unsettling aspect of the Willow Creek case isn’t the fire, or the arrogance of a man who wanted Latin prestige without Latin labor, or even the possibility of a clandestine escape. It’s the way a single mind, trained against the odds, made a closed system feel suddenly porous. It’s how the house changed when Jacob read. He didn’t swing a blade. He turned pages. And a world that justified itself by pointing to those pages could not bear to see them read so well by the person it called property. That collision is what burned.

Tell the story that way—grounded in documents, modest in speculation, clear about what’s known and what’s guessed—and you do two things at once. You hold the reader. And you honor the truth. That balance is how suspicion stays low and impact stays high. It’s also, fittingly, the same balance a translator must keep: fidelity to the text, with just enough art to make it live.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load