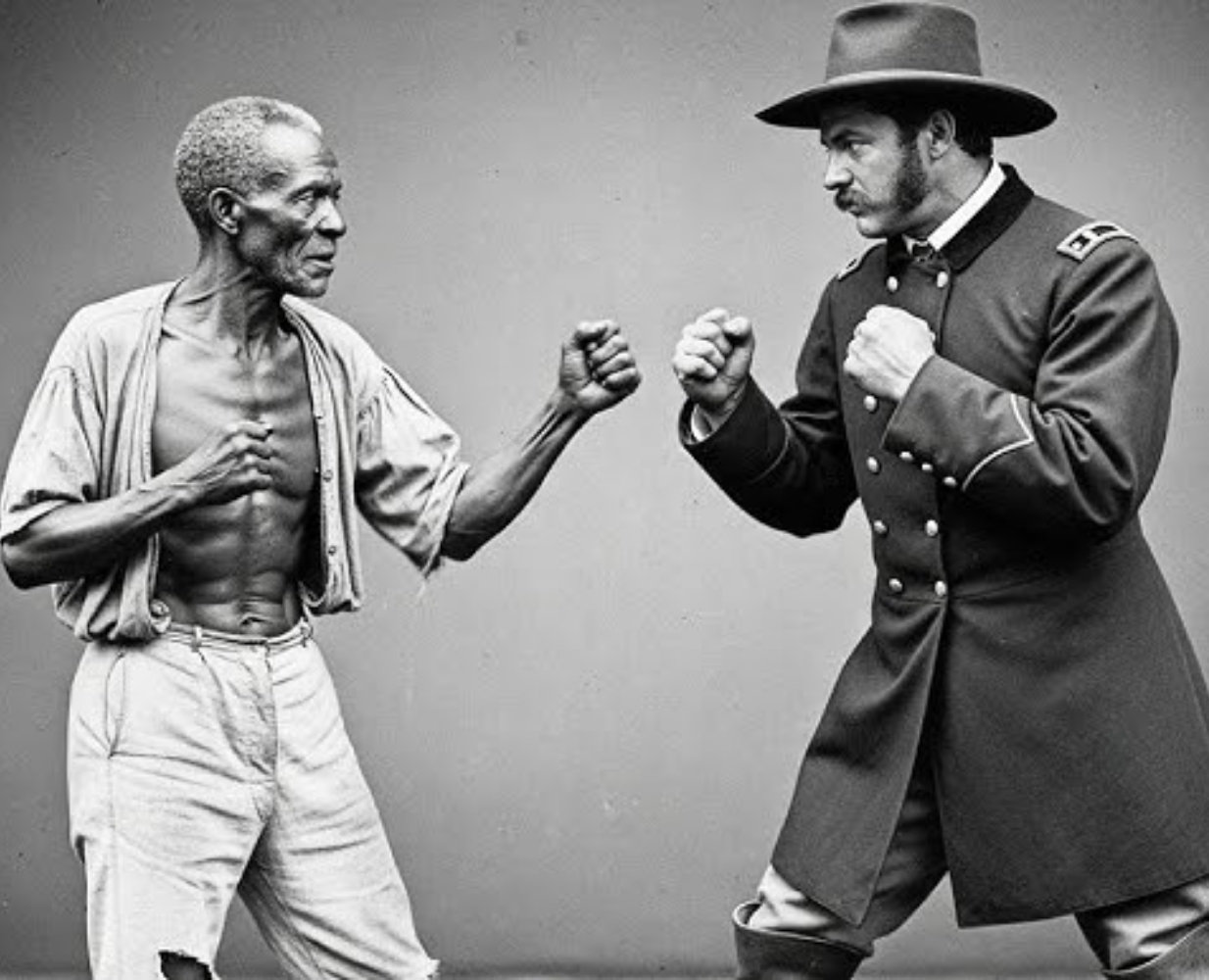

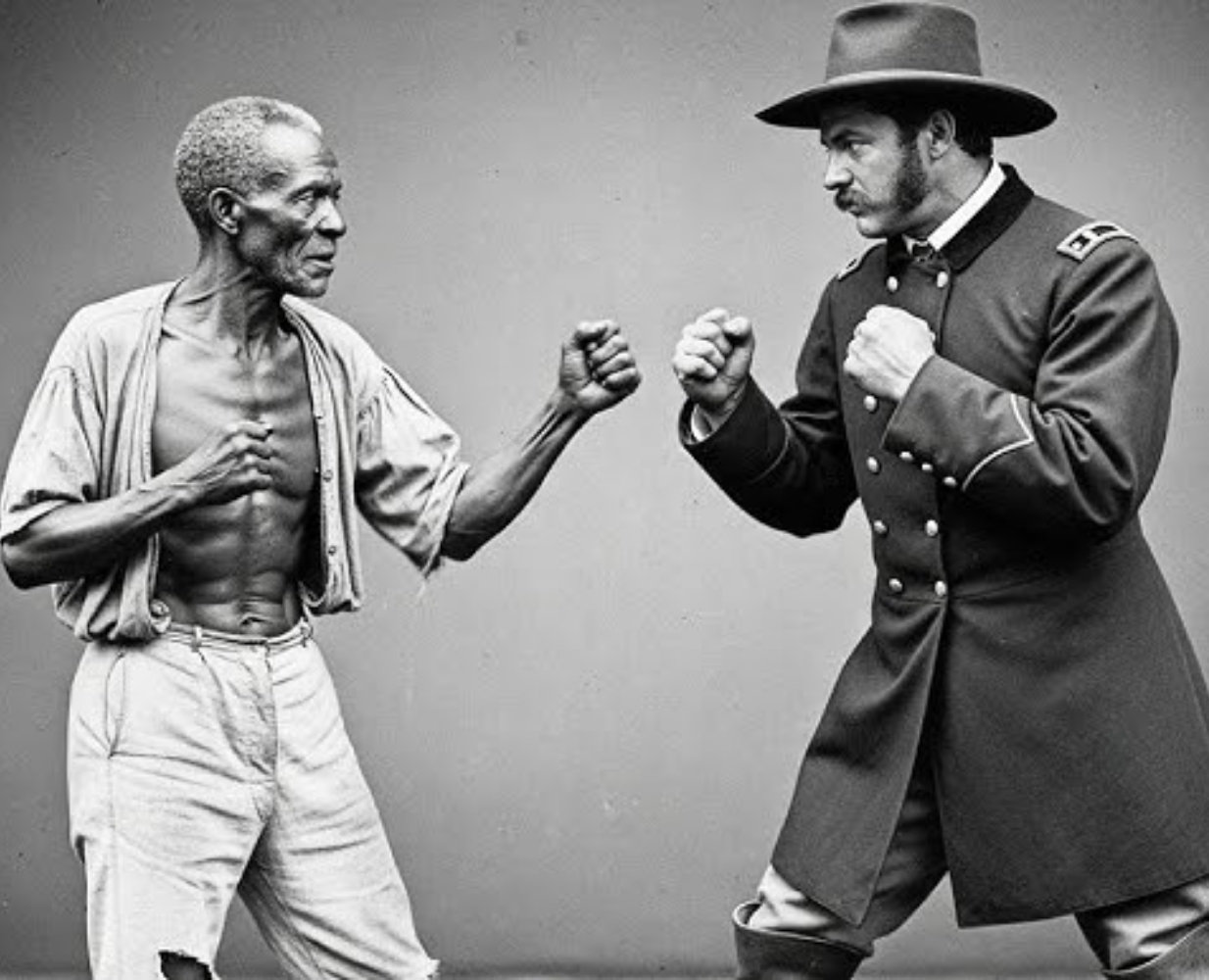

They called him Halfman, and on the cotton fields of Harrow Creek, the name stuck like a curse. Jeremiah Grant was sixty-five years old, thin as a rail, his skin stretched over bones that had carried more weight than any man should. His hands shook carrying a bucket of water, his shadow a crooked line on the red Georgia earth. To the young ones, he was a ghost, a body kept alive only because even the overseers thought him unworthy of a beating.

But the old men and women, the ones who remembered the before-times, knew better. They saw the way Jeremiah moved—quiet, careful, invisible—and they knew that sometimes, surviving meant being less than seen. Thomas Harrow, the master of the plantation, had given him the nickname decades earlier, laughing as he did, and the overseers used it as a weapon. “Move, Halfman! You’re slower than a dead man!” “Halfman ain’t good for nothing!” Jeremiah never answered. He’d learned that invisibility was armor, that being beneath notice was safer than being seen.

But inside that wasted frame, Jeremiah Grant carried a secret older than most men on the plantation. It lived in his muscles and bones, in memories of his father’s voice whispering across half a century. Solomon Grant had been a giant, hands big enough to palm a watermelon, a way of moving that made you believe he was only pretending to be enslaved. When Jeremiah was twelve, Solomon taught him something forbidden. On Sunday afternoons, when the white folks were at church, they’d slip away to the creek that cut through the property. Solomon would pull out a length of braided leather, supple as a snake, with a pouch in the middle and two loose ends.

“This here’s a sling,” Solomon said, voice low. “Same thing David used on Goliath. But that’s about all the white man’s Bible got right.” He showed Jeremiah how to pick stones from the creek bed, smooth and round, how to feel which ones wanted to fly. The stance, the grip, the rotation—Solomon explained that the sling was an extension of your arm, gathering speed and momentum until the stone became a bullet. “Count in your head,” he said. “One rotation to gather, two to aim, three to release. Let the leather talk to you.”

It took Jeremiah three months to hit his first rabbit. The stone caught it mid-hop, and the animal dropped like lightning had struck. Solomon smiled, rare and proud. “You got the gift. But listen close. Don’t never tell nobody. Not your friends, not your mama, not a soul. A negro with a weapon is a dead negro. But a negro with a secret weapon? That’s a free man waiting for his moment.”

For four years, Jeremiah practiced in secret. Rabbits, possums, birds in flight. Once, a deer. He and Solomon ate well those nights, deep in the woods where the smoke wouldn’t be seen. Then came the day everything changed. Three men from a neighboring plantation were caught hunting with slings. It didn’t matter they were trying to feed their children. The white men saw weapons in black hands and responded with violence meant to be remembered. The men were whipped and hanged from an old oak, their bodies left for days as a message.

That night, Old Master Harrow called all his enslaved people to the yard. “Any negro found with a sling, a rope for throwing, or any projectile instrument will receive fifty lashes and be sold south to the sugar plantations.” Solomon burned his sling that night. Jeremiah watched the leather curl and blacken, watched his father’s face show nothing. “I burned the leather,” Solomon whispered, “but I can’t burn what’s in here.” He tapped Jeremiah’s chest. “Nobody can take that.”

Jeremiah never made another sling, never threw another stone with intention. Solomon died of fever when Jeremiah was nineteen. Jeremiah was sold away two years later, then again, and again, each time moving further from everyone he’d known. By the time Thomas Harrow bought him for five dollars in Savannah, Jeremiah was forty-five—“Might get another ten years out of him,” Harrow said. “If he don’t die first. Look at him. He’s half a man already.” The name stuck.

But sometimes, before dawn, Jeremiah would walk to the creek, reach into the cold water, and pull out a stone. He’d feel its weight, test the balance, his fingers curling around it in a grip that remembered. He never acted on it, never let himself dream of what he could do. Because thinking about it meant thinking about everything else—the injustice, the cruelty, the casual evil of men who believed owning other human beings was not just acceptable, but righteous.

On April 13th, 1858, Thomas Harrow woke in the same brass bed where he’d been born, under the same portrait of his grandfather. He was fifty, in what he considered his prime, and he’d never questioned the world’s order. He owned forty-seven people, never called them that—his negroes, his workers. He prided himself on being a fair master, not like those who ruled through terror alone. He gave new clothes twice a year, allowed singing on Sundays, didn’t separate mothers from children unless “necessary for economic reasons.” These things, in his mind, made him good.

His wife Margaret knew better, but she’d learned that speaking uncomfortable truths to Thomas was like throwing water on a grease fire. Their son Robert, twenty-three, was becoming a problem. College in Charleston had filled him with dangerous ideas—education for negroes, gradual emancipation, the dignity of all souls. Last week, Robert had suggested allowing more water breaks during the hottest part of the day. Thomas had struck him across the face, and Robert hadn’t cried. That was almost worse.

Thomas needed to reassert control, to remind everyone of the natural order. When Dina, the house cook, reported three chickens missing, Thomas felt a surge of gratitude. Here was an opportunity. “Call Pike,” he said. “Find out who’s been thieving. I want them punished publicly today.”

Pike, the head overseer, lived to serve—or more accurately, to have power over those beneath him. He couldn’t command white men, but he could make the enslaved people’s lives hell, and that was enough. “We got a thief, Pike. Three chickens gone. I want every negro on this plantation to see what happens to thieves.”

Pike’s eyes lit up. “I know just the one. Halfman. That old skeleton, Jeremiah Grant. He’s always lurking around the chicken coop.” It wasn’t true, and Pike knew it. Jeremiah passed by the coop because it was on the way to the creek. But Pike needed a scapegoat, and Jeremiah was perfect.

Thomas nodded. Not a young buck full of rage, not a woman whose suffering might build resentment. An old man, already thought worthless. Halfman. The name itself did half the work.

“Bring him to the yard at noon,” Thomas said. “Call everyone. My family will watch from the porch. You and your men keep order.”

Jeremiah was sitting in the slave quarters, weaving a basket. His fingers, gnarled but precise, moved through the willow strips. He was thinking about Solomon, about the feeling of the first successful throw, about the night Solomon burned the sling and whispered that nobody could take what you carried inside.

Pike’s shadow fell across him. “Get up, Halfman.” Pike had two overseers with clubs. “You stole three chickens from Master Harrow’s coop.” Not a question—a sentence. Jeremiah kept his face still. “No, sir. I never stole nothing.” “You calling me a liar?” “No, sir. Just saying I didn’t take no chickens.”

“We’ll see what the master has to say about that. You’re coming to the yard. Noon. Everyone’s going to watch you get what thieves deserve.”

The slave quarters went silent. Some looked away; some looked at Jeremiah with pity. A few women cried quietly. The yard meant blood, screaming, the crack of the whip.

As Pike and his men dragged Jeremiah toward the door, his right hand brushed the torn hem of his pants, where three nights ago, for reasons he hadn’t understood, he’d hidden a length of braided leather, two yards of it, worked carefully in the dead of night. In his shirt pocket, three stones from the creek—smooth, round, perfect. He hadn’t known why he’d made the sling, why he’d collected the stones. It felt like instinct, his body preparing for something his mind hadn’t yet accepted.

Now, being dragged toward what would certainly be a public beating and possibly his death, Jeremiah understood. His body had known before his mind. The moment had arrived.

The yard was packed red clay between the manor house and the slave quarters. In the center stood a thick oak post, dark with old blood stains. Iron rings were bolted at different heights. By noon, the sun was overhead, offering no shade, no mercy. Thomas Harrow stood on the porch, arms crossed, face set in righteous judgment. Margaret sat behind him, working embroidery, her face blank. Robert looked sick.

Pike had gathered all forty-seven enslaved people into a semicircle. The field hands, house servants, children, elderly. Jeremiah was shoved into the center. Pike and four overseers stood around with clubs, one with a musket. Even with an old man, they weren’t taking chances.

Thomas descended from the porch, each step deliberate. He wanted this moment to carry weight. “Jeremiah Grant,” he said, voice carrying across the yard, “you have stolen from me. Three chickens. In the eyes of God and the law, you have committed theft. Do you have anything to say?”

Jeremiah raised his head. For twenty years, he’d avoided Thomas’s gaze. Now, he looked directly into the master’s face. “I didn’t steal nothing, Master Harrow. I never stole nothing from you or nobody else.” A murmur went through the crowd. You didn’t contradict the master. Ever.

Thomas’s face darkened. “So you’re not just a thief, you’re a liar. You will confess your sin, beg forgiveness, and accept your punishment. Twenty lashes. If you confess now, we’ll leave it at that.” Jeremiah said nothing. “I said, you will confess.” “Can’t confess to something I didn’t do.”

The silence was absolute. Even the birds seemed to stop singing. Thomas’s face went red, hands clenched into fists. “Pike, tie him to the post. Forty lashes. I want him to feel every single one.”

Pike moved forward, eager. That’s when Jeremiah took a step back. Not a stumbling retreat, but measured, balanced. His right hand went to the hem of his pants, and when it came up, he was holding a length of leather with a pouch in the middle.

“What the hell is that?” Pike stopped, confused. Thomas squinted. “What are you doing, old man? You think a piece of rope is going to save you?”

Jeremiah didn’t answer. His left hand went into his shirt pocket and came out with a smooth stone. He placed it in the pouch, movements slow and deliberate, like a ritual practiced ten thousand times.

Robert on the porch felt his blood run cold. He’d read about ancient slingers in college. That’s what the old man was holding. “Father, move back!” he shouted. “That’s a—” “Shut up, Robert,” Thomas snapped.

He was smiling now, cruelly. “Go ahead, Halfman. Show us what you’ve got.”

Jeremiah held the ends of the sling in his right hand, steadied the pouch with his left. Then he began to rotate his arm, slow at first, the leather humming through the air. The sound was strange, something ancient, triggering a deep fear. Thomas’s smile faltered. “What are you?”

Jeremiah’s arm moved faster. The circle became a blur, the humming a whistle. His thin body, so feeble before, now looked different—like a warrior. His eyes were focused, intense.

One rotation. Two. Three. On the third, Jeremiah released. The stone flew, crossing the eight yards between him and Thomas in less than a heartbeat. It struck Thomas in the center of his forehead, a sound like an axe hitting wood. Thomas’s head snapped back, arms dropped, eyes wide with shock. His mouth opened, no sound coming out. He fell straight back, heavy and final. The body hit the earth with a thud felt in every chest. Blood pooled under his head. He didn’t move. He didn’t breathe. He was dead before he finished falling.

For a moment that stretched into eternity, nobody moved. Nobody breathed. The world had inverted itself. A slave had killed a master. An old man had killed his owner. Halfman had proven he was whole.

Then Margaret screamed, a high, piercing sound that shattered the moment. Pike reached for his whip, but realized it wasn’t enough. “Kill him!” he roared. “Shoot him!”

The overseer with the musket raised it, hands shaking. Jeremiah already had another stone in the sling. His arm rotated, smooth, practiced. Two overseers with clubs charged. Jeremiah released. The stone caught the first in the nose—bones shattered, blood gushed. The second hesitated. Jeremiah’s third stone hit him in the throat—he dropped, choking. The musket fired, but the shot went wide. Pike dropped his whip and ran for the cabin. The other overseers ran for their horses, and didn’t stop until they were off the plantation.

The enslaved people stood frozen. Some cried, some prayed, some stared at Jeremiah like he’d become something divine and terrible. Jeremiah lowered the sling, hands shaking from the release of fifty-three years of rage and grief. He looked down at Thomas’s body and felt only emptiness where fear used to live.

Sarah, a young woman with five children, stepped forward. “What happens now?”

Jeremiah looked at her, then the others. “The militia will come. They’ll hang me. Probably some of you, too.”

Esther, who’d been at Harrow Creek longer than Jeremiah, nodded. “They’ll say it was a rebellion. They’ll burn the quarters.”

Moses, nineteen, strong, spoke up. “Then we run. Right now, before they get here. We follow the river north. Some of us know the way. Some heard about the Underground Railroad. We run or we die.”

Isaiah shook his head. “They got dogs, horses, guns. We won’t make it ten miles.”

Sarah said, “Maybe not. But I’d rather die running than die here on my knees.” She looked at Jeremiah. “You coming with us?”

Jeremiah looked at the sling in his hands, at Solomon’s legacy, at the proof that nobody could take what you carried inside. He looked at Thomas’s body and felt every chain, every scar, every moment of forced silence lift away.

“Yeah,” he said. “I’m coming. But not as a runaway slave. As a free man.”

Moses grinned, wild and fierce. “Then we’re all free, starting right now. Any of you coming?”

Twenty-one people stepped forward. Some older ones stayed, too frightened or broken. Some of the very young stayed with grandparents. But twenty-one souls chose death running north over death waiting in chains.

They had maybe three hours before Pike reached the sheriff and the militia was called out. They needed every minute.

Robert stood on the porch, watching his father’s body cool in the yard, feeling relief. He walked down the steps, the enslaved people watching him warily. “How long until Pike gets to town?” he asked Jeremiah.

“Two hours, maybe three.”

“Then you need to move fast. When they come, I’ll tell them it was just you, that you went crazy, that the others had nothing to do with it. Maybe they’ll believe me, maybe not, but it might buy the rest some safety.”

Sarah frowned. “Why would you do that?”

Robert cleaned his glasses, buying time. “Because my father taught me you were property, tools. Today I watched a piece of property kill its owner with a rock. Which means either my father’s worldview was a lie, or Jeremiah Grant is something other than property. I’m going with the second option. You’re a man. Always were.”

Jeremiah nodded. “Thank you.”

“Don’t thank me,” Robert said. “Just run. And when you get north, remember not all of us believed in this. Some of us knew it was wrong. We just didn’t have your courage.”

They moved fast, gathering what little they had. No time for sentiment, no time for goodbyes. Just movement, purpose, survival. Jeremiah led them, transformed from the shuffling old man into someone sure-footed and decisive. He read the land, hid their tracks, kept them moving through terrain that would kill them if they made mistakes. They followed the creek north, staying in the water to confuse dogs. Jeremiah taught them to brush away footprints, to move like ghosts.

That night they camped in a ravine. No fire. They ate cornbread and dried meat. The children cried quietly. Moses sat next to Jeremiah, watching him check his sling and count his stones. “How’d you learn to do that?”

“My father taught me. Long time ago.”

“Why didn’t you ever use it before?”

Jeremiah interrupted gently. “Could have killed a master and got myself hung, maybe half the plantation with me. My father told me to wait, to keep the skill hidden, to be patient. Today, they gave me no choice. And today, there were enough of us ready to run. That’s what made the difference.”

Sarah joined them, having just gotten her youngest to sleep. “How far we got to go?”

“Ohio River’s about 150 miles north. If we cross that, we’re in free territory. But they’ll come after us tomorrow, next day. We need to move fast and smart.”

“Can we make it?”

Jeremiah looked at her, saw the same fierce determination that lived in Solomon’s face. “We’re going to try. And trying’s more than we could do yesterday.”

For six days they moved north. Jeremiah kept them alive. He hunted with his sling, bringing down rabbits and squirrels, roasting them over smokeless fires. He found water, chose paths that avoided farms and roads, kept them moving and made them rest. On the second day, they heard dogs. Jeremiah made them wade through a creek, then walk across bare rock, then climb trees and travel through branches. The dogs lost the trail.

On the fourth day, Isaiah collapsed from fever. They carried him, but he died that night. They buried him in a shallow grave and kept moving. On the seventh day, exhausted and half-starved, they reached the Ohio River. The border between slavery and freedom was a wide band of brown water, four hundred feet across, swift and strong. On the other side was Ohio, free soil, the possibility of a life where nobody owned them.

They were trying to figure out how to cross when fifteen men on horseback appeared. The militia had caught up. Their leader, Dalton, the county sheriff, dismounted, rifle pointed casually. “Y’all had a good run. Made it farther than most, but it’s over now. Two choices. Come back peaceful or resist and get shot. Either way, you ain’t crossing that river.”

The fugitives stood frozen. The children cried. Sarah held them close. Moses and the others looked at Jeremiah, waiting for a miracle.

Jeremiah stepped forward, between the militia and his people. He still had the sling tucked in his belt, five stones left. “We ain’t going back,” he said quietly.

Dalton sighed. “Old man, I don’t want to shoot you, but I will. You killed a white man. You know what that means? You’re going to hang. Why make it worse?”

“Can’t be worse than going back to chains.”

“Last chance. Come peaceful or die here.”

Jeremiah pulled the sling from his belt, loaded a stone. Dalton’s eyes widened. “What the hell is that?”

“Something old,” Jeremiah said. “Something they thought they’d made us forget.” He began to spin the sling. Dalton raised his rifle, but he was too slow. The stone hit Dalton’s right hand, bones breaking like dry wood. Dalton screamed and dropped the rifle.

“Kill them!” a militia man shouted. Rifles fired, smoke and chaos. Jeremiah was moving, spinning, releasing. Another stone caught a man in the temple. Another shattered a jaw. The mounted men tried to aim, but their horses panicked. Moses and the others charged, pulling riders from horses, fighting with the desperate strength of those with nothing to lose. The battle was brief and brutal. Three more militia men went down from stones. Two beaten unconscious. The rest fled.

In the sudden silence, the fugitives stood among the dead, breathing hard, covered in blood and dirt. “Cross now,” Jeremiah said. They stripped off their clothes, bundled them on their heads, waded into the river. The current was strong, the water cold. They held onto each other, the strong supporting the weak, adults carrying children. Jeremiah went last, making sure everyone made it. When he finally pulled himself onto the far bank, Sarah reached down and helped him up. “Welcome to Ohio,” she said, smiling through tears. “Welcome to freedom.”

They found help from a Quaker family three miles north. The Hadleys fed them, gave clothes and shelter, connected them with the Underground Railroad. They traveled to Cincinnati, then to Canada. Not all made it. Two children died of fever. Esther passed away peacefully in a safe house. But seventeen souls made it to Canada, to true freedom.

Jeremiah Grant lived to be eighty-two. He never picked cotton again, never bowed to any man. He worked as a carpenter in Toronto, married a freed woman named Ruth, had three children who grew up knowing their father had killed a master with nothing but a stone and a sling. He never made another sling, but kept the old one tucked away with three stones from the Ohio River.

Sometimes his grandchildren asked him to show them how it worked. He’d take them to a field, send stones whistling through the air with the same precision as when he was young. “How did you learn to do that, Grandpa?”

“My father taught me,” Jeremiah would say. “He said they can take everything from you—your name, your family, your body, your time. But they can’t take what’s inside unless you let them. What you learn, what you know, what you carry in your heart and hands, that’s yours forever. And when the moment comes, it’ll be there waiting.”

“Were you scared, Grandpa, when you fought the master?”

Jeremiah thought long before answering. “Yeah, I was scared. But I was more scared of staying a slave. More scared of never knowing what it felt like to stand up. Your great-grandfather taught me to use that sling, but more important, he taught me I was a man. Whole. And once you know that in your bones, you can’t ever go back.”

He died in his sleep in 1875, seventeen years after killing Thomas Harrow. He was buried in Toronto under a headstone that read: Jeremiah Grant, free man. In his coffin, tucked into his coat pocket, were three smooth stones and a leather sling, waiting with him for whatever came next.

News

Gayle King speaks out on Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance: ‘Somebody knows something’

Gayle King is once again speaking out on the disappearance of Savannah Guthrie’s mom, Nancy Guthrie. “Somebody knows something,” the…

The identity of the imposter who sent the ransom letter claiming to be Nancy Guthrie has been revealed, and his testimony is shocking

A California man accused of sending phony ransom texts to Savannah Guthrie’s family about her missing mother has been arrested…

$1,6M Vanished in a 1982 Museum Theft — 35 Years Later, A Ring Surfaced in a Rap Video

In 1982, a priceless art deco jewelry collection vanished overnight from a traveling exhibition in Miami. No alarms sounded, no…

$850K Blackmailed From Factory Owner in 1990 — 3 Years Later, Press Recording Revealed the Truth

In 1990, a metal factory owner in Chicago received a demand for $850,000 in cash, accompanied by threats to expose…

She Won $265K at the Slots in Vegas in 1994 — Seven Days Later, Her Husband Was K!lled

A week after a Detroit warehouse supervisor hit a life-changing jackpot in Las Vegas, her husband was found dead on…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case

He hitchhiked across the South with nothing but a backpack, a plan, and a promise to call his sister when…

End of content

No more pages to load