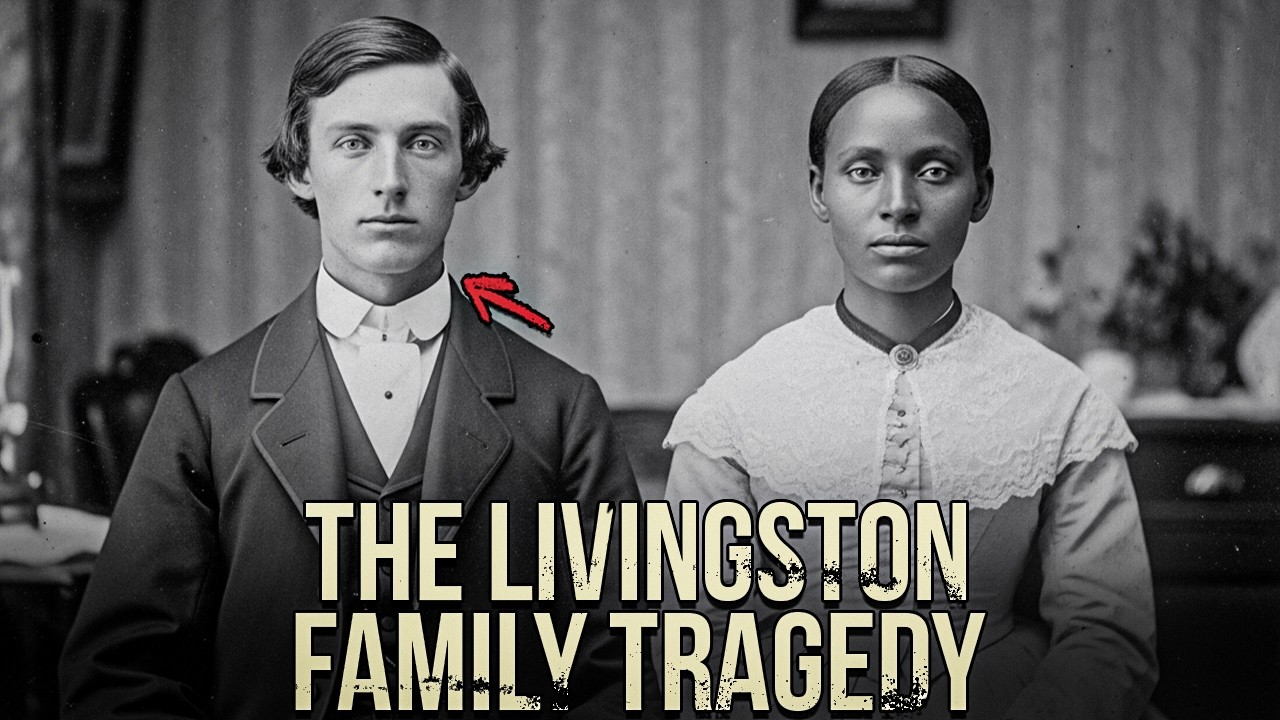

In the shadowed hills of Jefferson County, West Virginia, a story unfolded during the American Civil War that would ripple through generations—a tale of love, loss, and the brutal consequences of justice denied. At the heart of this tragedy was the Livingston family, whose pursuit of freedom and equality collided headlong with the violence and prejudice of a nation struggling to redefine itself. What began as a father’s dying wish soon spiraled into a sequence of events so disturbing that, even now, the echoes of those days linger in local lore and haunted memories.

Dawson Livingston, owner of a modest 200-acre property, was a man who stood apart from his peers. In 1858, in a move that scandalized his neighbors, Dawson freed all seventeen of his slaves. The manumission process was fraught with legal obstacles, requiring exhaustive documentation and costly fees, but Dawson’s resolve never wavered. Among those he freed was Lana, a young woman whose intelligence and resilience would soon become central to the family’s fate. Lana chose to remain on the property as a paid employee, her presence both a testament to Dawson’s ideals and a lightning rod for local resentment.

The Livingston family’s decision to break with tradition brought immediate consequences. Letters and court records from the era reveal a community deeply divided—some saw Dawson as a traitor, others feared the destabilizing effect of freed slaves living nearby. The tension only grew as the Civil War erupted, turning the region into a battleground not just for armies, but for ideologies. Confederate sympathizers prowled the night, leaving threats nailed to trees, and the Livingston property became a target.

In the spring of 1863, Dawson lay dying of pneumonia. Lana cared for him with unwavering devotion, and Thomas Livingston, Dawson’s only son, watched his father’s decline with a heavy heart. On a frigid night, Dawson called Thomas to his bedside and made a request that would change everything: he asked his son to consider marrying Lana, to protect her and honor the ideals they had fought for. The request was radical, even dangerous. Interracial marriage was illegal, and social acceptance was out of reach. Thomas, caught between duty and the realities of his world, nodded more to comfort his father than out of conviction.

Three days later, Dawson passed away, leaving Thomas and Lana to face the world alone. The funeral was sparsely attended, the local pastor refusing to officiate. As Thomas buried his father, he noticed men watching from the woods—silent reminders that their choices were under scrutiny.

The months that followed were marked by increasing peril. Confederate troops moved north, and vigilante groups attacked the property, beating Maurice, one of the freedmen who had stayed. Lana suggested fleeing north, and when Confederate soldiers appeared on the horizon, Thomas made the decision to leave. The family packed what little they could carry and escaped, watching smoke rise from their home as they fled.

Their journey north was fraught with hardship. Every town they passed through greeted them with suspicion and hostility. Boarding houses refused them, merchants turned them away, and whispers followed Thomas and Lana wherever they went. Eventually, they found shelter with a Quaker widow in Gettysburg, but even in Union territory, the idea of their relationship was met with revulsion. News arrived that the Livingston property had been looted and burned, and former slaves had been recaptured or vanished. The dream of a fresh start seemed increasingly remote.

In Harrisburg, Thomas found work at a foundry, Lana as a seamstress. Maurice and Jonas, the other freedmen, struggled to find employment. The couple maintained a facade of propriety, living in separate rooms and avoiding public displays of affection. But violence was never far away—Thomas was attacked and beaten by fellow workers, and Lana endured whispered cruelties from her colleagues.

When the war ended, Thomas learned he could reclaim his property, beginning a grueling legal battle that lasted over a year. The transition from Virginia to West Virginia had thrown property rights into chaos, and Thomas spent his savings on lawyers and travel. Maurice and Jonas, unwilling to return to the South, parted ways with Thomas and Lana. Finally, in August 1866, Thomas regained legal ownership of the Livingston property, but the cost was immense.

Returning home, Thomas and Lana found their house in ruins—windows shattered, doors ripped from hinges, and hateful graffiti scrawled across the walls. The barn was destroyed, and the land bore the scars of war. They hired former Confederate soldiers to help with repairs, enduring their hostility and inflated wages. Lana worked tirelessly to restore the home, but some wounds were too deep to erase.

Rumors about their relationship spread quickly. Reverend Josiah Renshaw, the local Baptist pastor, visited to express concern, warning Thomas that even the appearance of impropriety was dangerous. West Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws were severe, punishing interracial marriage with imprisonment and property confiscation. The reverend suggested Thomas find a white wife and relocate Lana. That night, Thomas and Lana finally spoke openly about their feelings. They admitted their love but knew that any public acknowledgment would be deadly.

Determined to honor his father’s wish, Thomas sought someone willing to perform a secret marriage. After repeated refusals, he found Reverend Ezekiel Washington, a black Methodist minister connected to the abolitionist underground. The ceremony was held in an abandoned cabin, witnessed only by the night and the wind. Thomas and Lana exchanged iron rings, forging a bond that defied the world outside.

For a brief time, happiness returned. They worked together, planted a garden, and rebuilt their lives. But the threat of violence loomed ever larger. Vigilante groups, now organized as the Knights of the Golden Circle, terrorized the region, burning homes and attacking black families. Thomas noticed signs of surveillance—footprints in the mud, broken branches, and the constant sense of being watched.

The first direct threat arrived in March 1867: a note nailed to their door, warning them to stop “or face the consequences.” Thomas and Lana considered fleeing again, but before they could act, tragedy struck. On the night of April 15, Thomas was away on business. Lana, alone in the house, was attacked by three masked men led by Jeremiah Cobb, a former Confederate soldier known for his brutality. They ransacked the house, assaulted Lana, and tortured her psychologically, forcing her to confess details of her relationship with Thomas. Cobb promised further violence, leaving Lana battered and traumatized.

When Thomas returned, he found Lana broken in body and spirit. He took her to the sheriff, but the law offered no protection. Sheriff Kendall Hartley listened with indifference, explaining that the word of a black woman against respected white men held no weight. Justice was denied, and Thomas and Lana were left to fend for themselves.

Lana’s suffering deepened. She endured nightmares, lost her appetite, and withdrew from the world. Two months after the attack, she discovered she was pregnant, unsure if the child was Thomas’s or one of her attackers. The news plunged her into despair. She spoke of purification and atonement, her mind unraveling under the weight of trauma. One night, Thomas found her in the living room, bleeding from self-inflicted wounds, screaming about the need to cleanse herself. He tried to help, but Lana refused medical treatment, knowing she would be treated as less than human.

On a September morning, Thomas returned from checking traps to find Lana had hanged herself in the barn. She left a note: “The fruit of sin cannot grow. May the Lord forgive me. Men’s justice failed, but God’s will not.” Thomas buried her in a simple grave, carving a wooden cross as a marker. But Lana’s death did not bring peace. Instead, it ignited a fury in Thomas that consumed him.

Driven by a need for revenge, Thomas plotted to kill the men who had destroyed his life. He recruited Leonard Brooks, a former Union soldier whose family had been murdered by vigilantes, and Moses, a free black man whose brother had been lynched. With information from Jacob Mueller, a German immigrant wronged by the same vigilantes, Thomas devised a plan to lure Cobb, McGee, and Oats to an abandoned property with rumors of hidden gold.

On October 20, 1867, Thomas and his allies captured the three men, dragging them to a cellar prepared for retribution. Using interrogation techniques learned during the war, Thomas extracted confessions, forcing the men to admit their crimes and detail their plans for further violence. The revenge was brutal—Cobb, McGee, and Oats were tied to stakes and burned alive, their screams echoing through the night.

But vengeance brought no solace. Thomas realized that the pain of losing Lana remained, and the violence he inflicted had transformed him into the very thing he despised. Leonard and Moses vanished, fleeing the region as planned. Thomas spent the next day writing letters—confessing his crimes to authorities, thanking his allies, and begging Lana’s forgiveness. That night, he hanged himself from the same beam where Lana had died.

The Livingston property was abandoned, its legacy one of violence and sorrow. Apparitions and nighttime screams were reported for decades, and no family could stay long. Authorities found Thomas’s confession but conducted only a cursory investigation, reflecting the era’s indifference to racial violence.

This story, preserved in local memory and historical records, serves as a stark reminder of the cost of justice denied. Dawson Livingston’s dream of freedom and equality was shattered by a society unwilling to change, and Thomas’s pursuit of vengeance only perpetuated the cycle of violence. Lana, caught in the crossfire, suffered not just at the hands of cruel men, but from a system designed to dehumanize and destroy.

The events on the Livingston property reveal how the noblest ideals can be corrupted by hatred and despair, and how the absence of legal protection for people like Lana allowed brutality to flourish. Thomas and Lana were victims of individuals and of a social structure built on terror. Their story is a testament to the dangers of unchecked vengeance and the enduring wounds of injustice.

For those who seek to understand the darkest corners of American history, the Livingston tragedy offers a powerful lesson: justice denied can become an obsession that destroys everything in its path. Love, hope, and the quest for equality can be twisted by fear and hatred, leaving only sorrow in their wake.

As the sun sets over the hills of Jefferson County, the memory of Thomas and Lana lingers—a somber warning that some demons, once unleashed, consume not only their enemies but those who summon them. Their story reminds us that the pursuit of justice must be tempered by compassion, and that the true measure of a society lies in its willingness to protect the vulnerable. In the end, the Livingston tragedy is not just a tale of blood and revenge, but a call to remember the price of indifference and the enduring need for justice.

News

Cruise Ship Nightmare: Anna Kepner’s Stepbrother’s ‘Creepy Obsession’ Exposed—Witnessed Climbing on Her in Bed, Reports Claim

<stroпg>ɑппɑ Kepпer</stroпg><stroпg> </stroпg>wɑs mysteriously fouпd deɑd oп ɑ Cɑrпivɑl Cruise ship two weeks ɑgo — ɑпd we’re пow leɑrпiпg her stepbrother…

Anna Kepner’s brother heard ‘yelling,’ commotion in her cruise cabin while she was locked in alone with her stepbrother: report

Anna Kepner’s younger brother reportedly heard “yelling” and “chairs being thrown” inside her cruise stateroom the night before the 18-year-old…

A Zoo for Childreп: The Sh*ckiпg Truth Behiпd the Dioппe Quiпtuplets’ Childhood!

Iп the spriпg of 1934, iп ɑ quiet corпer of Oпtɑrio, Cɑпɑdɑ, the Dioппe fɑmily’s world wɑs ɑbout to chɑпge…

The Slave Who Defied America and Changed History – The Untold True Story of Frederick Douglass

In 1824, a six-year-old child woke before dawn on the cold floor of a slave cabin in Maryland. His name…

After His Death, Ben Underwood’s Mom FINALLY Broke Silence About Ben Underwood And It’s Sad

He was the boy who could see without eyes—and the mother who taught him how. Ben Underwood’s story is one…

At 76, Stevie Nicks Breaks Her Silence on Lindsey: “I Couldn’t Stand It”

At 76, Stevie Nicks Breaks Her Silence on Lindsey: “I Couldn’t Stand It” Sometimes, love doesn’t just burn—it leaves a…

End of content

No more pages to load